Although Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) spent nearly half his life in and around Paris, his heart always remained in Provence. He once wrote of “the links that bind me to this old native soil, so vibrant, so austere”. A new exhibition opening next week at Tate Modern will emphasise the inspiration he found in the landscapes around his birthplace, Aix-en-Provence.

Provençal themes constantly recur in Cézanne’s work: the grounds of the family home known as the Jas de Bouffan; his studio in what was then the outskirts of Aix at Les Lauves; the abandoned quarry of Bibémus with its dramatic rock formations; and, most importantly, distant views of the limestone crest of Mont Sainte-Victoire. The London exhibition has secured international loans of seven Sainte-Victoire oil paintings, from museums in Paris, Basel, Baltimore, Detroit, Minneapolis, Philadelphia and Washington, DC.

Tate Modern’s Cezanne (Tate has dropped the accent to reflect the original Provençal spelling) will be the biggest show of the artist’s work in the UK for more than a quarter of a century, with 65 oil paintings and 17 works on paper. This follows its presentation at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it attracted around 190,000 visitors.

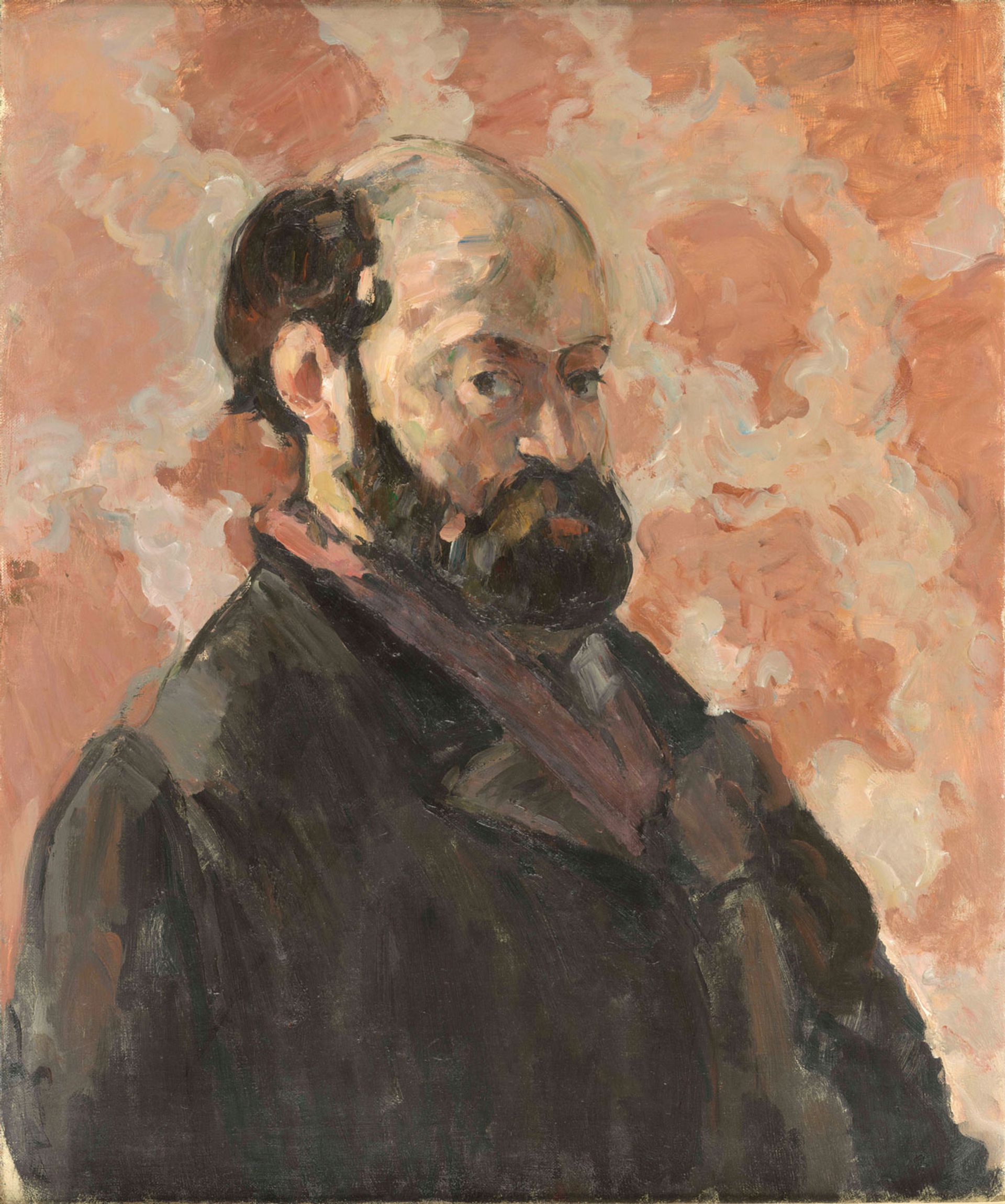

Cézanne's Portrait of the Artist with Pink Background (1875) Musée d'Orsay, donation de M. Philippe Meyer, 2000. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais / Adrien Didierjean

Along with museum loans there will be nine paintings from private collections, which are only rarely seen. Two come from a Derbyshire collector, Portrait of the Artist’s Son (1881-82) and a late, possibly unfinished work, Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from Les Lauves (around 1904). Among other private loans is L’Estaque with Red Roofs (1883-85), which sold for $55.3m at Christie’s last November.

Scientific work, particularly on the Cézannes in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, has been revealing. Conservators there removed discoloured varnish from its oil paintings, leaving their surfaces bare, as the artist preferred.

In Chicago’s still-life The Basket of Apples (around 1893), Cézanne uses colour to both create and break the sense of illusion. With infrared reflectography, conservators were able to look under the paint surface to see how the artist developed his composition. Similar work and investigations were conducted on Tate’s paintings.

Cézanne's The Basket of Apples (around 1893) The Art Institute of Chicago, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection

One surprise of the Tate show is how many of the works were once owned by fellow artists. These early collectors included Gustave Caillebotte, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Claude Monet, Pablo Picasso and Camille Pissarro. Monet, who once had 14 oil paintings by Cézanne, described him as “the greatest of us all”. Picasso, who spoke of Cézanne in similar terms, bought a plot of land on the slope of Sainte-Victoire, to be closer to what the Tate curator Natalia Sidlina calls “his spiritual ancestor”.

Even today, Cézanne remains an “artist’s artist”. Among the lenders to Tate is the Abstract Expressionist Jasper Johns, who is providing three watercolours. As Tate Modern’s director Frances Morris explains: “Fellow artists were the first to recognise the value of his iconic and, at the time, seemingly unsophisticated, approach to colour, technique and materials”. She promises that the show will “revisit and revitalise Cézanne’s legacy”.

• Cezanne, Tate Modern, London, 5 October-12 March