Fresh from representing France at the Venice Biennale, the London-based French-Algerian artist Zineb Sedira opens a solo exhibition Can't You See the Sea Changing? at the De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, on the south coast of England (24 September- 8 January 2023).

In photographs, videos and installations dating from 2011 onwards, the show returns to a recurring obsession of her artistic practice—the sea, rich in multi-layered symbols and memories of migrant identity.

“The sea was a leitmotif in my life for a long time,” Sedira says. “My parents migrated from Algeria to France by boat in the 60s, then I migrated from Paris to London by boat in the 80s.”

“The sea can be a space of confinement or of freedom, depending on which side of the world you are,” she says. “If you come from the South, it’s a kind of barrier to most of Europe but if you’re in Europe, it’s more a space where you can explore and travel to other countries.”

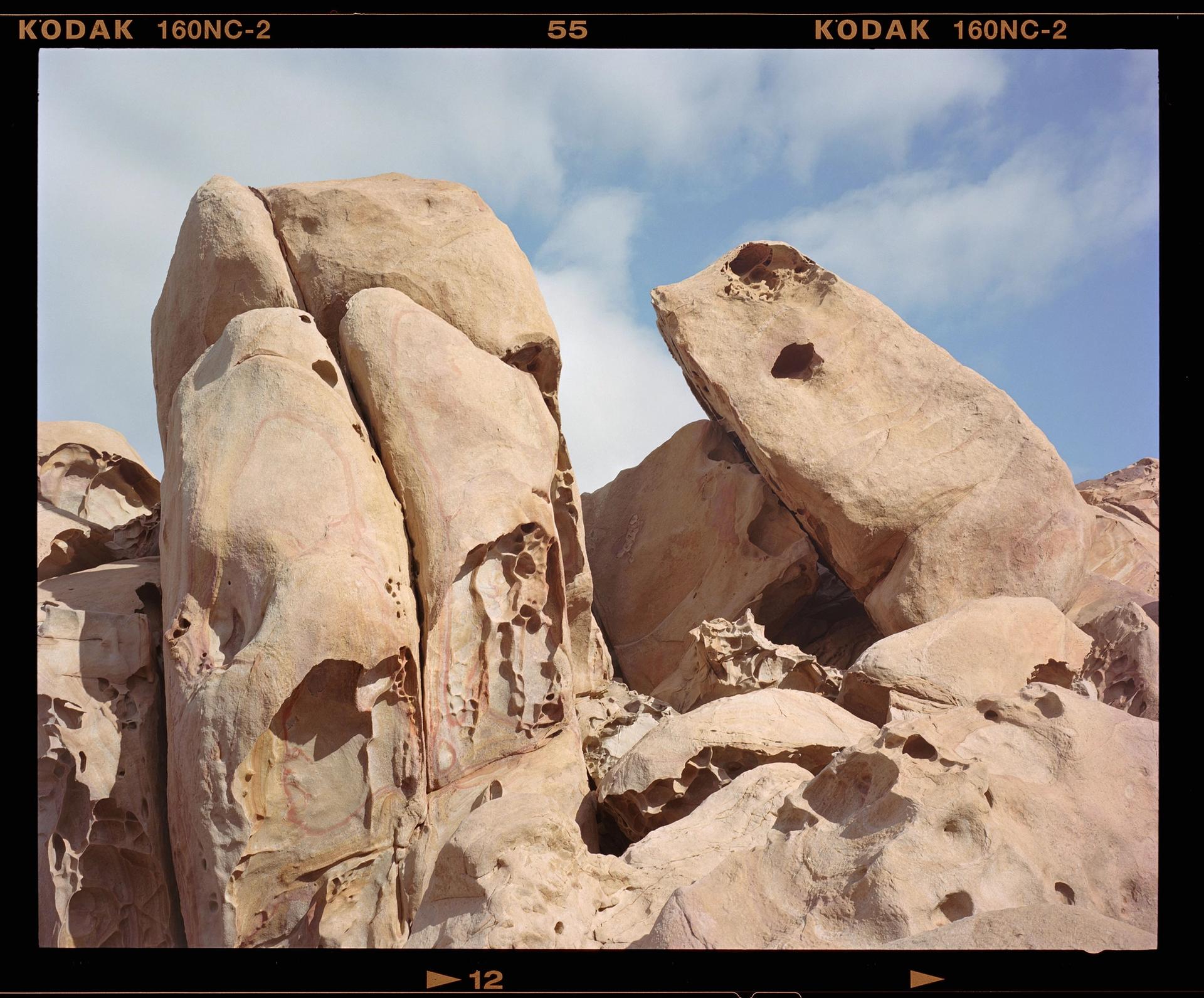

Zineb Sedira's Sea Rocks, (2011-22) Courtesy of the artist, kamel mennour and Goodman Gallery

In a year when up to 60,000 refugees are predicted to land on the UK’s south coast beaches, the Bexhill show may have a particular poignancy, though it features no direct references to current migration crises.

Partly that’s because it was planned to open more than two years ago, before the Covid-19 pandemic struck—and before the refugee crises triggered by events such as the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan or the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

More fundamentally, it reflects Sedira’s artistic practice. “I work more with metaphors and analogies rather than pinpointing particular disasters or political stories,” she says. “When I talk about the sea it’s about all types of migration, whether legal or illegal.”

Rather than focusing on the present, the show, spread over two floors of the gallery, offers tangential meditations on past histories, not least those of her parent's generation navigating the dislocations of a post-colonial world.

A still from Sedira's Transmettre en abyme (2012) Commissioned by Marseille-Provence 2013, European Capital of Culture and the Port of Marseille. Courtesy of the artist, Kamel Mennour and Goodman Gallery

Her three-channel video installation, Transmettre en abyme (2012), conjures the North African exodus to France through a 50-year series of photographs, curated on-screen by the Marseilles gallery owner Hélène Detaille, recording the movement of ships in the French port city.

Lighthouses, signals of safe passage and danger, chart a passage through the show. Lighthouse in the Sea of Time (2011), another multi-screen film and sound installation, explores the symbolism of two lighthouses built under French colonial rule to guide shipping through the eastern and western approaches to Algiers. Registre du phare (2011) illuminates Algeria’s journey to independence in 1962 through the daily logbook of a lighthouse keeper.

Sedira’s artistic vision is both physical and metaphysical. Sea Rocks, a photo observation of eroded boulder formations on the Algerian coast, references the shaping powers of waves over time, erasing memory and history. Other photographs pass a clinical scanner’s eye over the deserted ruins of French colonial seaside villas in Algeria and Nouadhibou’s port on Mauritania’s Atlantic coast—the world’s largest graveyard of abandoned rust-buckets and a historical transit point for African migrants risking the sea route to Spain. Next to these Sedira has set a partial replica of her Brixton studio, including her collection of vintage marine objects and books.

Brixton, a hub of London’s Caribbean-African community, was a scene of race riots in the 1980s and 90s. But for Sedira, arriving in 1986, it was a safe haven from the anti-North-African racism she grew up with in France after Algeria’s war of independence. In Brixton, as non-white and non-Black, she passed under the radar: “Algeria meant nothing to people,” she says.

Still, “in Brixton I could see Black people suffering like I did in France,” she adds. “Which is why I made a lot of friends with people like Sonya Boyce. I could recognise myself in their stories.”

“I am much closer to the [British] Black art movement than the Young British Artists, for instance. All my work is about looking at any form of racism, whether it’s through a colonial situation or a post-colonial situation.”