The South African artist William Kentridge draws with remarkable speed and with a showman’s sense of invention and fun. He has made films and staged productions of everything from opera to puppet shows. He can also talk his way through all this media as well as anyone, as he does in the new nine-part television series Self Portrait as a Coffee Pot, three episodes of which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on 12 September.

Perhaps it was only a matter of time before an artist of Kentridge’s vast reach found his way to television, or before television found him. He has a natural jargon-free manner of talking about making art and about the places where art is made. His work draws from a vivid, albeit fallible, memory as we learn in the series.

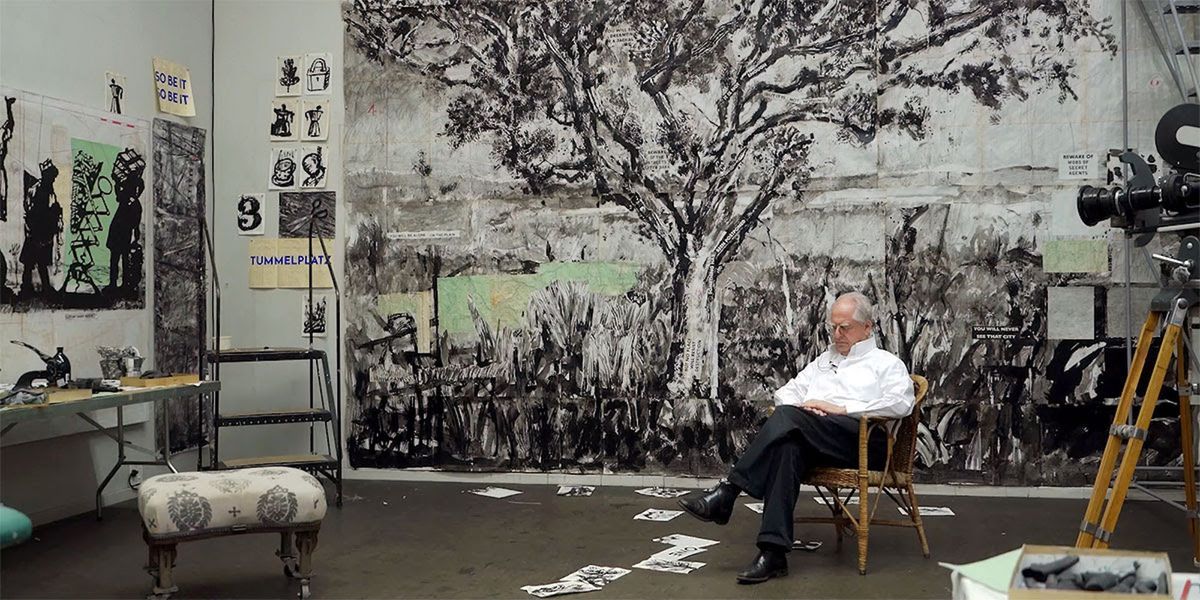

Probing and entertaining, Self Portrait as a Coffee Pot began in Kentridge’s studio under a coronavirus lockdown. In the three episodes, shown in Toronto as one film presentation, there are almost always two of him on the screen (sometimes more), parrying away in a philosophical dialogue in black trousers and a white shirt like figures inspired by the classic comedian Oliver Hardy.

The stage for these performances is the studio, which is also one of the film’s subjects. “The world is fragmented. Those fragments are allowed to swirl around the studio and then rearranged and then sent back into the world as a drawing, as a film, as a story,” he says. “It’s a place of undoing certainties, of allowing for a kind of provisionality. The job of the artist is to allow the world to fragment and see what can be remade with it.”

Kentridge is working with many layers here, starting with his double-figured self, and extending to animated “mice” crawling around the place, made from the pages of printed books which he had his double tear up. He always seems to be drawing, or talking about it. “Can we escape who we are? I think of myself as an artist making drawings. Even when the charcoal is replaced by the spoken word or by an ink word,” he says.

All this comes with a warning issued years ago to artists, and to himself, who might aspire to the Gesamtkunstwerk: “You start thinking of drawing a picture of the whole universe, and you end up with a coffee pot.” Let us hope that a future episode will address the serene pots of Giorgio Morandi and the everyday objects in Picasso’s Cubist paintings.

If Kentridge’s art is rooted in his drawing, it is also rooted in his biography. He claims that he “was reduced to being an artist” after lacking the skills to be an orchestra conductor, and notes that his native Johannesburg has an art museum only because a prominent woman there urged the moneyed mining elite to seek a legacy beyond extracting wealth from the ground beneath them and shipping it to London. We still remember South African magnates more for their crimes than for their collecting.

If some of this sounds familiar, it distills, refines and dramatises much of what Kentridge discussed in his six wide-ranging Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard, delivered in 2012 and published in 2014 as “Six Drawing Lessons”. Those lectures, with videos, multiple Kentridges and music, seem like concert performances compared to the produced film, but still provide crucial context.

A one-man band (with double) when he started filming, Kentridge left the music to the fragmentary and soothing improvisations of Kyle Shepherd (piano) and Nhlanhla Mahlangu (vocals) with occasional bridges away from unruliness with Franz Schubert’s elegiac String Quintet in C. It all makes you want to see more.