"The dog barks and the caravan moves on." That old saw usually describes the trajectory of the art world. Not lately. With the September openings of the Armory Show and the Museum of Modern Art’s Wolfgang Tillmans retrospective sounding the first woofs of the season, the caravan appeared to stop at a crossroads and look for a way back.

Perhaps the successive convulsions of the Trump presidency, Black Lives Matter, Covid, Russia’s war on Ukraine and the passing of Queen Elizabeth II have left everyone so unsettled that the art of the past offers the best option for stability. Whatever the reason, the moment seems to privilege the historical more than any disruption that one might expect from new art.

I did see a ton of smart and splendid work by all kinds of artists from disparate parts of the globe. But a tour of galleries in Chelsea and Tribeca created the distinct impression, reinforced by the Armory’s 247 exhibitors, that artists have been exploring the material, formal and conceptual strategies of the old guard and refreshing, deepening, or aping them without breaking new ground. Just putting an explicitly personal stamp on it—particularly when it comes to representing the bodies of Black women. Standouts in this category at the Armory were Genevieve Gaignard at Vielmetter Projects and Nona Faustine at Higher Pictures Generation.

But overall, it looked as if artists from very different cultures were all speaking the same language. One might say the same about the 1980s, but artists who came of age then aggressively upset the status quo. For good and ill they transformed the market and brought a larger public to work that keeps cycling through successive generations. Yet, the bigger the market for art gets, the less potent it feels. Though often appealing, arresting, and vibrant, the current crop seems so respectable, even reverent, toward its antecedents, while making the ever-bigger statement and the grander gesture.

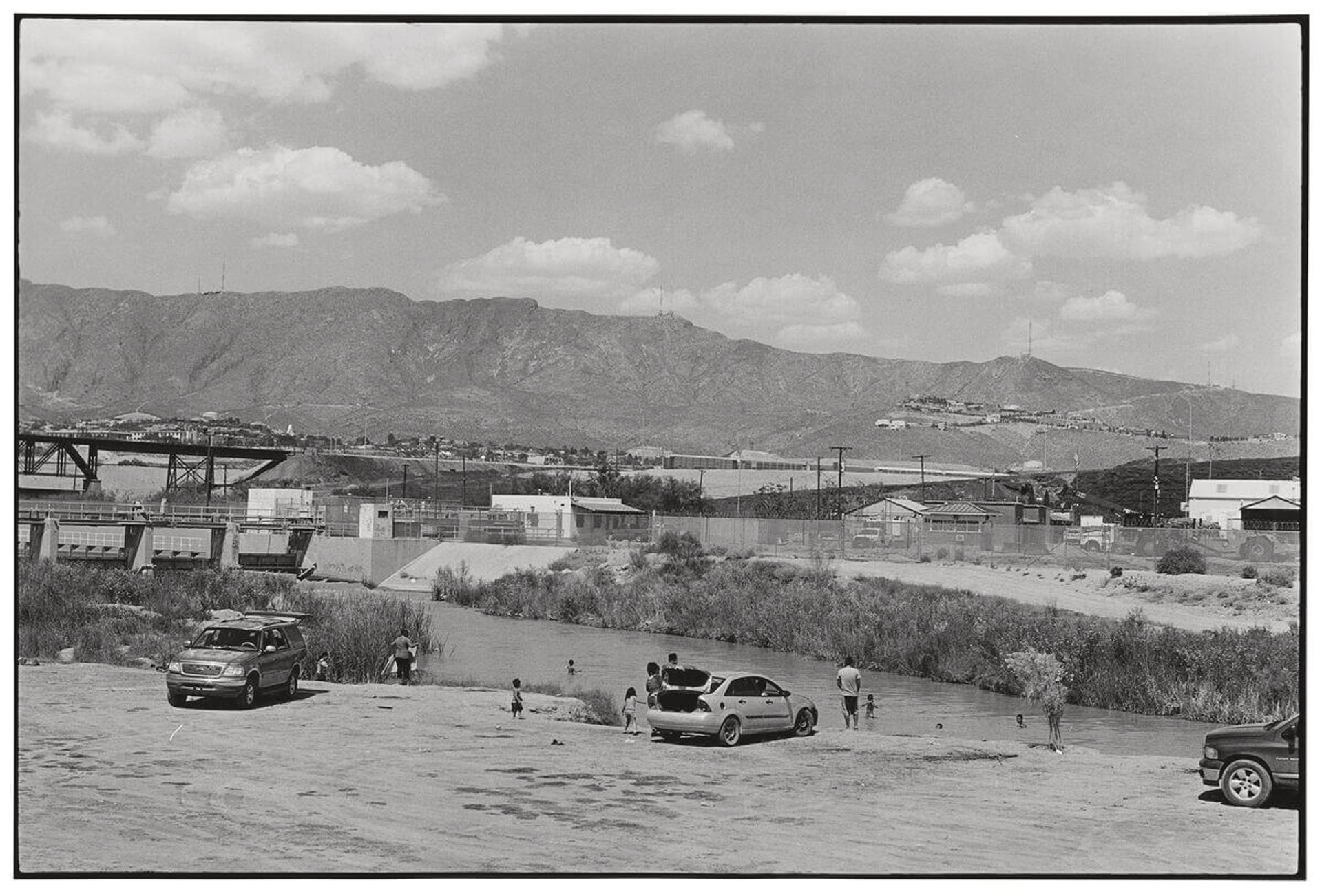

From Zoe Leonard's Al río / To the River series at Hauser & Wirth New York. © The artist and Hauser & Wirth

That may be why Zoe Leonard’s selection of quiet, modestly sized, hugely meaningful black-and-white photographs in her latest project, Al río / To the River at Hauser & Wirth came as such a breath of fresh air. Leonard spent nearly six years exploring the 1,200 miles of the Rio Grande that forms the unconstructed wall between the US and Mexico, resulting in nearly 500 images. “I wanted to see what happens when we make a river into a mark of political identity,” she told me. She did not leave out the wreckage people have made of the surrounding environment. If typical of her serial approach to a subject, the show sets itself apart by being both current and contentious.

The other winner for transformative subtlety was at Ortuzar Projects, where Cathy Wilkes was making her New York gallery debut. Though the Glasgow-based Wilkes had a surpassing show at MoMA PS1 in 2017 and represented Great Britain at the 2019 Venice Biennale, her installations are so muted and so subjectively wrought that their presence can take time to register. Then they kick you in the gut.

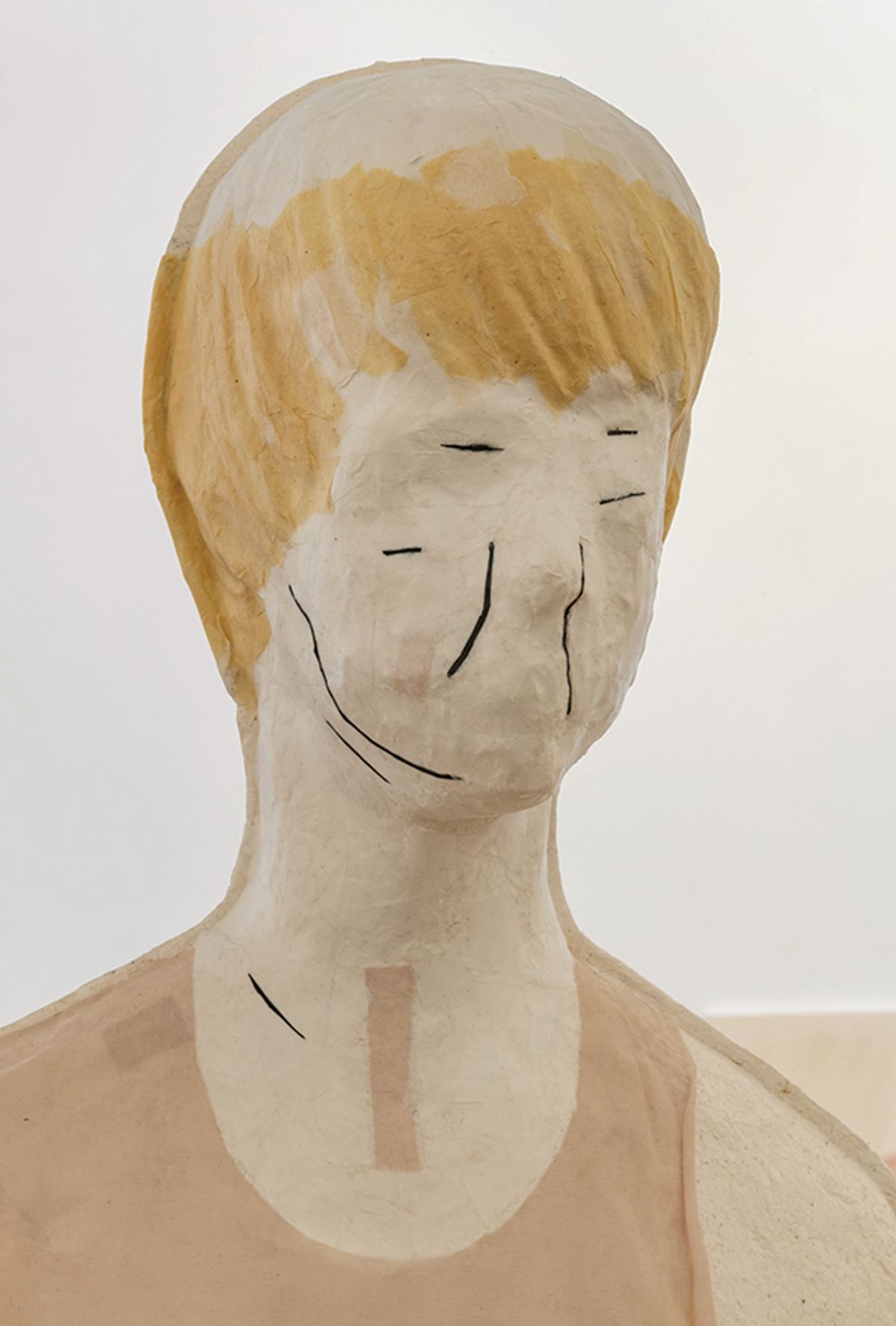

Installation view of Cathy Wilkes at Ortuzar Projects. Photo: Patrick Jameson

At Ortuzar, her paintings are all hung very close to the floor, just above such forlorn objects as a child’s balled-up sock that sits under a tamped-down abstraction bearing a single silhouette that points to the poignant, mother-daughter relationship grounding the show, though that is anything but obvious. One has to look hard to make out the word “mother” in a deftly brushed painting of what could be a clouded sky. A freestanding female mannequin is partly draped in torn pieces of light fabric. A folded undergarment in a vitrine of “personal objects” speaks volumes about both sculpture and Wilkes's process. The sense of loss apparent in items found finds its equal in an outpouring of love—or so it seemed to me—enormous feelings expressed by an accumulation of almost nothing at all. It’s a private world. One had to trespass its borders to come to grips with it.

Up to now, Ales Ortuzar has given his gallery over to resuscitating works from older artists or estates. To show new work by Wilkes, who exists apart from the mainstream New York market, makes a statement of its own. “Well, you know,” he said at a dinner for Wilkes that drew a phalanx of visiting Glaswegians. “It’s time.”