They hail from very different disciplines, but when the Italian theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli joined forces with the artist Cornelia Parker to discuss quantum physics last month, it was an inspired—and inspirational—meeting of great minds. And one that uncovered much common ground between the two. This erudite exchange took place in the illustrious setting of Conway Hall in Bloomsbury, which since the 1920s has been the headquarters of the Ethical Society, the oldest surviving free-thought organisation in the world.

As the conversation ranged across art, science and politics, there was also the added frisson that Parker and Rovelli were occupying the same stage as many of the Society’s epoch-defining speakers, including Charles Darwin, William Morris, HG Wells, Bertrand Russell and the Suffragettes Marion Phillips and Marion Holmes.

Cornelia Parker's Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View

Both physics and science in general have long been an inspiration for Parker, and many of her works encapsulate the most mind-boggling scientific concepts in poetic and idiosyncratic ways. Most famously in 1991 she persuaded the British army to blow up a garden shed stuffed with everyday clutter before suspending its blasted fragments, constellation-like, around a single lightbulb under the title Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View. A creative reflection on the Big Bang Theory, the work was also made at the time of the IRA bombings in the UK. It is now one of the most popular works in Tate’s collection and features prominently in Parker’s major retrospective at Tate Britain (until 16 October). Other scientific forays include harnessing the incendiary properties of graphene—the thinnest and strongest known material—to trigger a firework display, and taking microscopic photographs of the chalk marks on a blackboard made by Einstein during his 1931 lecture on the Theory of Relativity, resulting in images that bear a striking resemblance to comets, galaxies of stars and matter particles.

But whether Parker is working with Nobel Prize-winning scientists, the British army or any other of her myriad collaborators from every conceivable walk of life, she was keen to stress that the elaborate negotiations, conversations and processes she engages in while making her multifarious oeuvre are as much a part of the work as the end product. This is borne out by the detailed labels in her Tate Britain exhibition, which she insisted on writing herself, and which tell the often intricate back story of every work on show.

And it turns out that Rovelli feels very much the same way about his sub-atomic particles, which he asserts do not come into being until they interact with each other. According to Rovelli’s particular “relational” interpretation of quantum theory, which is the subject of much of his recent writings, reality is “not a collection of things, it’s a network of processes”. This, he says, pushes us to rethink reality “in terms of relations, instead of objects, entities or substances”. So, as the Conway Hall conversation unfolded, what emerged was not so much the story of quantum physics as a trans-disciplinary love-in between artist and scientist as they explored the surprisingly close correspondence between Parker’s collaborative, event-intensive approach to artmaking and Rovelli’s notion of “relational quantum mechanics”.

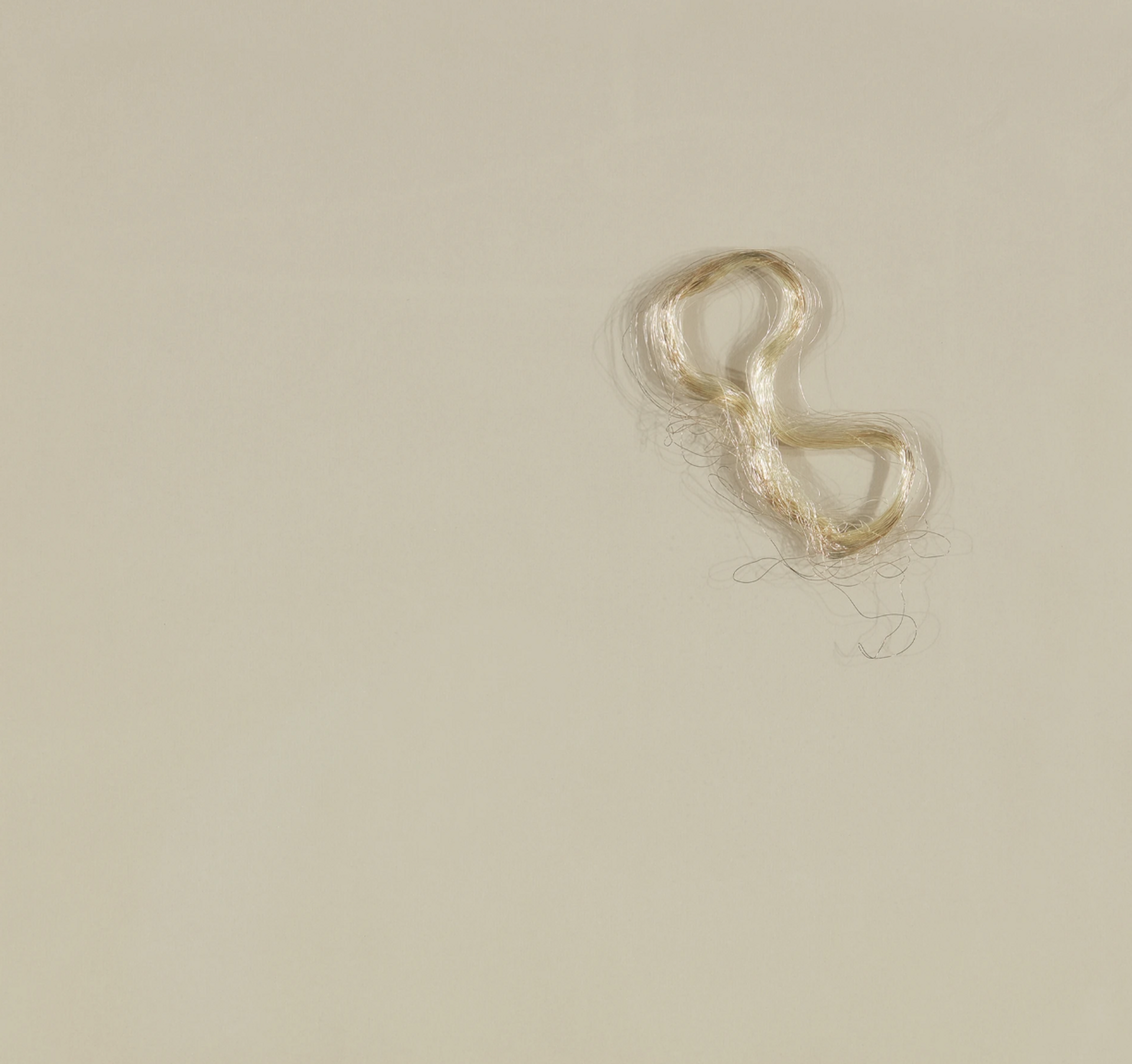

Cornelia Parker's Measuring Liberty with a Dollar (1998)

Both believe that the world that we observe is continuously interacting and that reality is better understood as a web of interactions and relations rather than specific discrete objects. Rovelli’s particles have no properties until they interact with something else. Much in the same way, Parker’s works of art are subjected to elaborate processes that often radically transform their appearance and meaning while at the same time leaving their constituent stuff unchanged. Thus in Measuring Liberty with a Dollar (1998), Parker’s bundle of silvery wire only springs into life as a work of art in the knowledge that it is a silver dollar pulled into a wire the height of the Statue of Liberty, while at the same time being the same piece of silver that was once a coin. In each of their rethinkings and reshapings of reality, nothing is fixed and relationships are all. Or as Rovelli puts it: “Objects don’t have interactions with each other; they are those interactions.”

In this mutable world view of interactions rather than things, uncertainty reigns supreme. But a lack of certainty is here seen as a positive source of dynamic possibility and greater understanding. As Rovelli puts it, “the search for knowledge is not nourished by certainty: it is nourished by a radical absence of certainty”. This is something we should all take to heart. Matter of life, materials of art, in the end it is all the same stuff, and the more interconnected and fluid our world view, and the more we realise that all of life is solely comprised of relationships—whether at a sub-atomic, social or political level—then the more we have to take responsibility for these relationships and their consequences.

• You can listen to this talk here