Boasting dazzling paintings in Prussian blue and gold, the famed Peacock Room by James McNeill Whistler is the most visited gallery at the Smithsonian Institute’s Freer Gallery of Art (part of the National Museum of Asian Art). So it’s only natural that the space—originally a London dining room and the only extant decorative interior by Whistler—requires an occasional deep clean and refresh.

This summer, the Freer closed the gallery to conduct a major conservation project that was the largest in three decades. Conservators focused on cleaning all the painted and gilded surfaces but also reinforced the room’s magnificent shutters, which feature handpainted peacocks. Officially titled Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room (1876-77), it will reopen on 3 September with an installation of ceramics that shows the room as it appeared when owned by the industrialist and museum founder Charles Lang Freer.

Conservation work being done on James McNeill Whistler's Peacock Room at the National Museum of Asian Art. Courtesy National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

“Rooms, when they’re continuously open to the public, get some wear and tear, naturally,” Diana Greenwold, the Freer’s curator of American art, says. “We’ve taken really wonderful care of it, but we really hadn’t done a major look across at the stability of the room as an object with our conservation team. We made every effort to not add new aspects but really make sure that what we were doing was bringing the space as close to Whistler’s original vision as we could.”

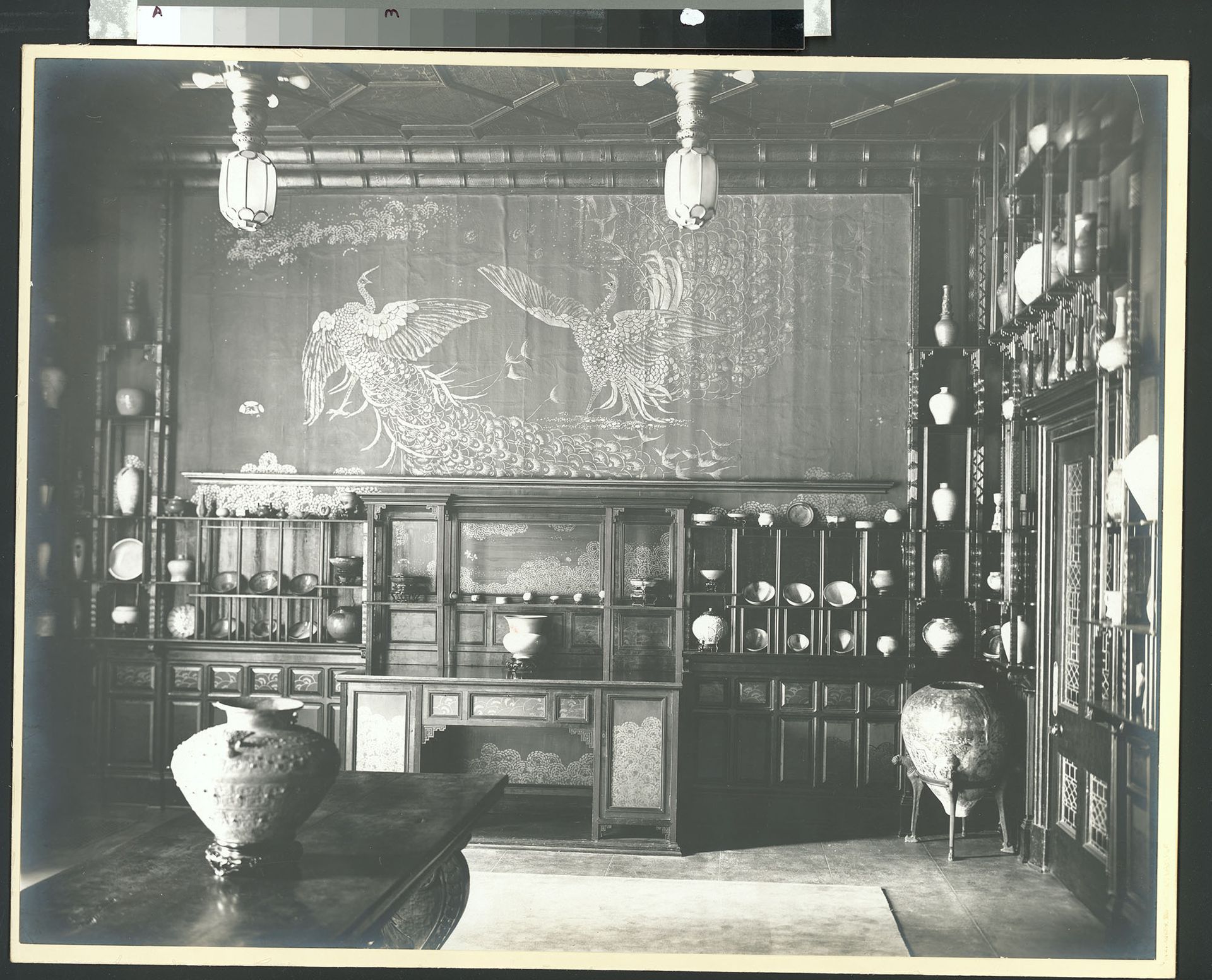

James McNeill Whistler, Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room, (1876-1877), as it appeared in the Detroit home of Charles Lang Freer. Charles Lang Freer Papers, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Gift of the estate of Charles Lang Freer, 1906. George R. Swain

Open to the public at the Freer since 1923, the Peacock Room is an exemplar of Gilded Age grandeur, with its gilded walnut shelves, soothing blues and greens and marvellous avian-inspired embellishments. However, it was never supposed to look like that. Its original owner was the British shipping magnate Frederick R. Leyland, who had commissioned Whistler in 1876 to redecorate the dining room in his London home so he could display his collection of blue-and-white Chinese porcelain. Leyland favoured subtle tones and complex surfaces textures, but Whistler followed his own extravagant vision, ultimately surprising his patron when he returned from vacation.

Their friendship disintegrated amid a bitter feud over aesthetics and money, but Leyland kept the room as is. After his death in 1892, the Peacock Room—which could be taken apart and reassembled—was purchased by the businesswoman and collector Blanche Maria Georgiana Burrell Watney, who sold it to Freer in 1904. Freer had it shipped to his Detroit home, where it remained until gifted, upon his death, to his namesake museum in Washington, DC.

Conservation work being done on James McNeill Whistler's Peacock Room at the National Museum of Asian Art. Courtesy National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

It wasn’t until the late 1940s that the room underwent restoration to retouch some of the surfaces, but the result was a “heavy-handed application of overpainting, some of which was done pretty clumsily”, Greenwold says. The next major conservation effort occurred from 1989 to 1992, which brought the room closer to its original look. “It was one of those kinds of high drama, Sistine ceiling kind of moments where layers of grime were removed to reveal a totally vibrant and revamped decorative programme.”

This most recent project involved much more subtle interventions. Conservators, led by the museum’s exhibitions conservator Jenifer Bosworth and objects conservator Ellen Chase, stabilised the shutters and metal floor vents—which were untouched during the 1990s restoration, cleaned layers of grime and repaired damage caused by heavy visitation. The shutters and grates are “themselves intricately decorated,” Greenwold says. “They shine now in a kind of holistic way with the rest of the space.”

James McNeill Whistler, Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room, 1876-1877. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer. Courtesy the National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

The Freer typically keeps the shutters closed to showcase their impressive paintings but also to avoid damage from sunlight. It previously opened them once a week to demonstrate how the room shimmers in natural light, but stopped doing so because of the pandemic. The effect is especially striking when Freer’s ceramics are on view, as he favoured high-lustre, iridescent works, most of them from East Asia and the Middle East.

This presentation will be recreated when the Peacock Room reopens, with curators referencing archival photographs of the space as it appeared in Detroit in 1908. “What you get from that is not only a kind of wonderful microcosm of Freer’s collecting interests and his tastes—from Syria, Japan, China, Korea—but you also see his wonderful capacity to use the full space almost as a decorative object in and of itself,” Greenwold says. “He arranges them often by groupings of colour. He kind of paints the space with these individual objects that then combine to make this glorious whole.”

James McNeill Whistler, Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room, 1876-1877. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer. Courtesy the National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

The conservation and installation were planned as part of the National Museum of Asian Art’s centennial celebration in 2023, a moment when the institution is reflecting on its past but also considering how to tell Freer’s story in new ways. The terms of the founder’s will dictates that, in general, only objects from the collection can be on view in the galleries, but curators are exploring different ways to have “more contemporary reflections”, Greenwold says, through tools like digital storytelling and audio. “There are ways that we can begin to unravel some of the stories around Orientalism, around cultural appropriation, that are endemic to a space like this. That’s something we’re certainly exploring in the next couple of years.”

- The Peacock Room at the National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, DC, reopens on 3 September.