Martine Syms’s solo exhibition, She Mad Season One, is a conceptual project in the form of a semi-autobiographical TV show. Unfolding across episodes made between 2015 and 2021, the experimental sitcom follows a young graphic designer, also named Martine and also living in Los Angeles, as she tries to make it as an artist. Composed of five video works installed on either side of a zigzagging metal structure that cuts across the gallery, She Mad draws on staged scenes, clips of TV shows, social media and memes to sketch a narrative around Martine’s daily life.

Syms is best known for her work in video that centres Black representation in popular culture, often by way of satire and digital media. Referring to herself as a “conceptual entrepreneur”, Syms has a practice elastic enough that it can encompass not only work across media, including graphic design and publishing, but also projects in branding—her collaborators have included Prada, Nike x Off White and Kanye West. Syms situates this work as part of a larger practice between art and life, and as a pragmatic question of survival as an artist.

But she is also noteworthy for making video work that is, at times, cinematic and narrative-driven, at times analytical and, at times, as it is in She Mad, nonlinear and experimental. While TV clips figure prominently in these videos, She Mad is itself distinctly un-TV-like. There are no character arcs or plotlines, although there is a catchy opening jingle. The project has the feel of a series of visual notes about the making of a future show, rather than the outline of a legible series in itself.

Installation view of Martine Syms: She Mad Season One at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Photo: Nathan Keay; © MCA Chicago

This effect is amplified by the montage of snapshot-like photos, culled from Syms’s personal archive, which plays between each screening: empty parking lots, hands removing candles from a birthday cake, giant teddy bears slouched into rolling office chairs, the album cover of a band whose name is a racial slur, palm trees against a glassy building, the contents of a refrigerator. Shot in the vein of what I think of as art school vernacular—bad flash, diagonal composition, a vague sense of alienation, a blurring of the urgent and unremarkable—the images cycle across each of the five screens. These recurring photos give the exhibition a muted ethnographic quality, like viewing the contents of someone’s Google Drive in full.

Quotidian Blackness

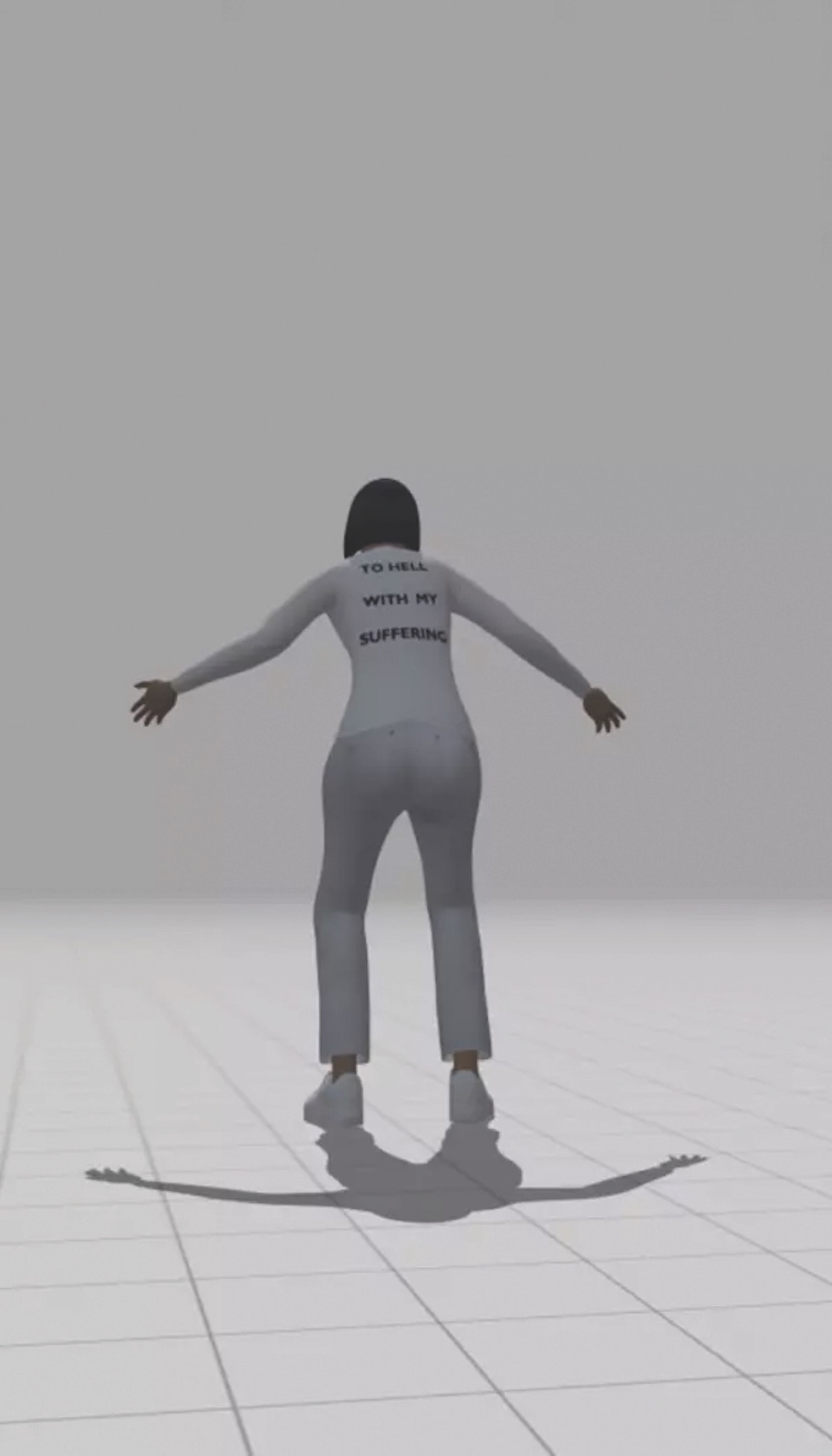

This makes sense, given Syms’s ongoing focus on everyday narratives in Black cultural production. In her 2013 work The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto she critiques the central tenets of Afrofuturism (“the connection between the Middle Passage and space travel is tenuous at best”) and praises a sort of quotidian Blackness instead. In a cultural context that too often presents Black characters as perennial “others”, sensationalises Black suffering or erases identity and structural violence altogether, Syms is interested in the political possibilities of a Black banality. In Intro to Threat Modeling (2017), a 3D-modelled representation of the artist dances around in a T-shirt emblazoned with the text “To Hell With My Suffering”.

Martine Syms, Intro to Threat Modeling, 2017, still. Courtesy of the artist and Bridget Donahue, New York

In the context of this larger atmospheric project, moments of narrative or theoretical clarity take on added significance in shaping the work as a whole. One of these touch points is the plot of the second video in the work, Laughing Gas (2016), which references an early silent film in which a woman visits a dentist who gives her nitrous oxide. In Syms’s video, Martine meets the same fate. We see her at a dentist’s appointment, scrolling through her phone in the examination chair; shortly after having her wisdom teeth removed, a dental assistant informs her that the $1,700 bill is not going through to her insurance and asks if she has another way to pay for it (“You want to maybe give dad a call?”). Martine runs away from the office and boards a bus, but because she’s under the effects of the gas, she can’t stop laughing. The scene recalls both the history of medical abuses against Black Americans as well as the costly farce that is the US healthcare system.

Avoiding clear representation or a linear narrative altogether, what Syms suggests with She Mad is a strategy to also avoid these pitfalls

But it’s a moment in the first piece in the series, A Pilot For a Show About Nowhere (2015), which suggests why Syms has avoided narrative convention for this project. Framed as a pilot episode for the season, it begins with Martine imagining what the show would be like. “The opening sequence would have an establishing shot of Los Angeles. Probably the 1-10-10 interchange downtown, none of that Hollywood shit,” Martine-as-narrator says. The episode cycles through clips of early shows and the long history of racist stereotypes in film and television; Syms traces the first sitcom to a radio show voiced by two white actors in blackface, which was in turn based on a minstrel show. In one of several talking heads segments that deal with TV and Black representation, an interview subject notes that although The Cosby Show was able to appeal to many Black viewers because it presented its affluent characters as a normal family facing everyday issues, it also erased any of the real challenges that poor and working-class Black people face. Avoiding clear representation or a linear narrative altogether, what Syms suggests with She Mad is a strategy to also avoid these pitfalls. It cannot fail its subject, because its subject refuses to be contained.

One of the possibilities offered by presenting TV-like work in an exhibition space is playing with the sense of linearity between episodes. Syms makes compelling use of the audio, with sound from one video blending into that of another. The steel structure that cuts across the space —painted a deep purple (Syms has said that her signature use of this tone forces people to say “the colour purple” aloud, referencing Alice Walker’s famed 1982 novel)—also allows for easy movement between episodes in any order: although placed chronologically, moving from right to left, the screens are installed on either side of the framework, and gaps between the girders make for easy passage from one viewing area to another.

Martine Syms, Bitch Zone, 2020, still. Courtesy of the artist and Bridget Donahue, New York

The last episode of She Mad, called Bitch Zone (2020), which plays on a large transparent LED screen set into the back corner of the steel structure, parodies the artist’s actual experience of attending a summer camp at age 13 run by the supermodel Tyra Banks. Set in the year 2000, the scene is acted out by Syms’s contemporaries (their impeccable early-Noughties fashion sense—centre-partings, puka shell necklaces and all—lends period veracity). A character named BBQ takes the stage in front of the seated campers and launches into a motivational speech about body positivity.

The tableau takes on a garish quality, though, when BBQ has the young women play what’s supposed to be a teambuilding activity. Because race isn’t discussed enough in the US, she says, it’s time to have it out in the open by saying aloud different racial stereotypes. “White people can’t digest spice,” says one camper; another responds, “Black people have thick nails.” “Asian people don’t have sweat glands,” shouts a third. Shot in red and black, the group becomes increasingly enraged and the camera spins upward as they begin to attack each other.

It’s a poignant end to She Mad, the exhibition and the season. It’s both humorous and almost unwatchably dark in its spot-on satire of how strained talking about identity and structural violence is in a country so deluded about its own history that teaching about slavery in school curricula remains a divisive issue. In Bitch Zone, Syms’s camera delights in the chaos, converting pain into entertainment. And as viewers, we too participate in the spectacle. “To hell with my suffering,” as Martine—auteur, avatar or character—declares on the back of her shirt, deflecting voyeurism as much as she acknowledges its structural power and the impossibility of avoiding it.

- Martine Syms: She Mad Season One, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, until 12 February 2023

- Curators: Jadine Collingwood and Jack Schneider