In 1912, rare books dealer Wilfrid Voynich was rooting through dusty chests of manuscripts in Villa Mondragone, a Jesuit college just outside of Rome. The Jesuits had decided to sell some of their centuries-old collection and had invited him to see if anything might be of interest. As he explored, Voynich found, in his own words, an “ugly duckling”—a manuscript like no other. Turning the pages, his eyes fell on unusual illustrations and mysterious symbols that formed a unique and unreadable script. He immediately recognized its value. Voynich bought the manuscript, and it wasn’t long before it excited imaginations across the globe.

Today, the Voynich Manuscript, as it became known, is kept in Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Scholars have pored over its content for over a century, but no one has managed to understand its meaning. Do the Voynich symbols encipher a known language? Or are they the alphabet of an invented one? Is the content gibberish? What do the book’s illustrations mean? And what is its purpose? Such questions—and the lack of answers to them—have led it to be dubbed the world’s most mysterious manuscript.

The facts

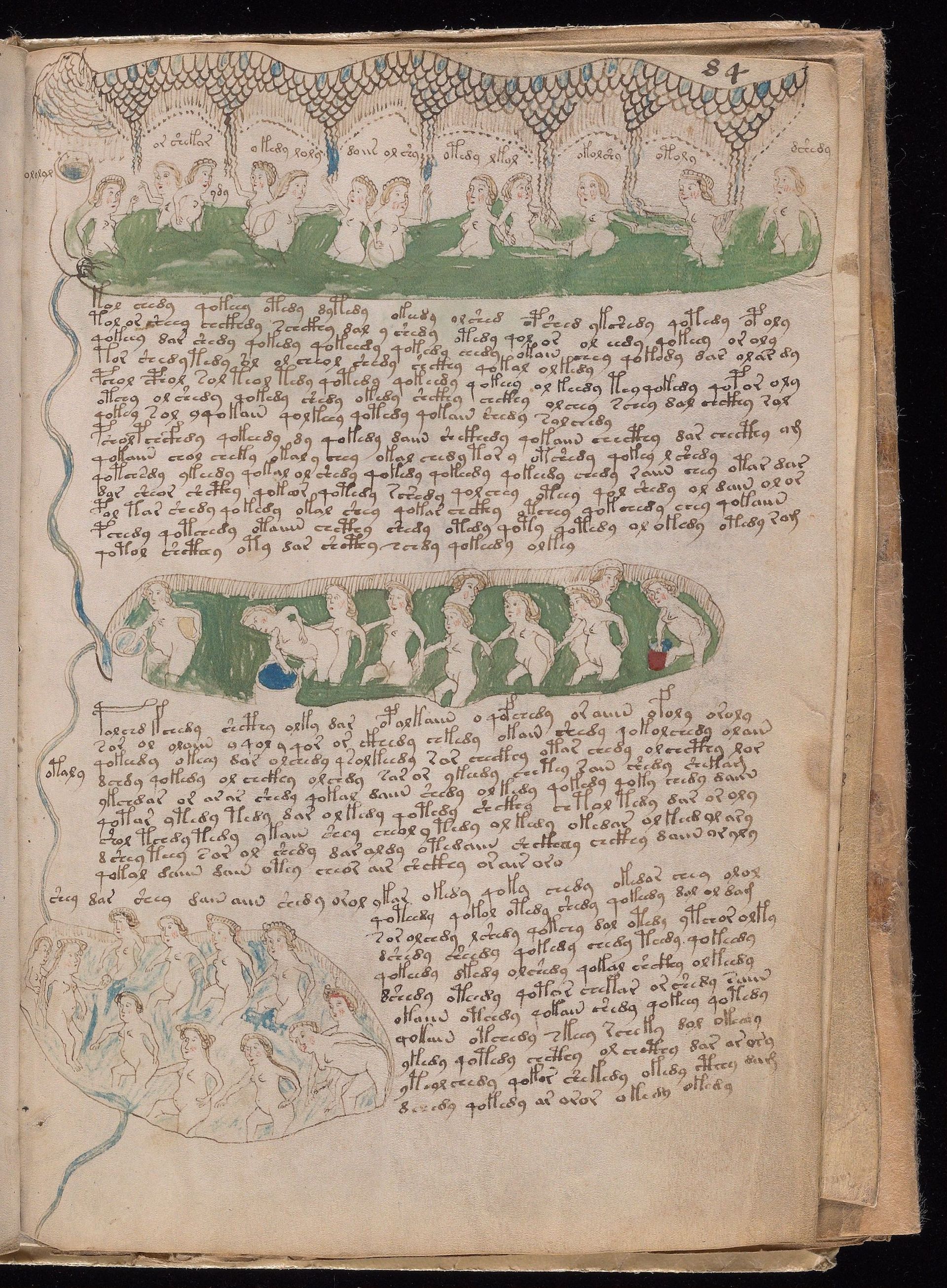

A page from the Voynich Manuscript Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

Although much remains a mystery, recent scientific investigations have greatly improved our understanding of its origins and creation. Scientists have radiocarbon-dated its vellum to between 1404 and 1438, and have shown that its scribes used iron gall ink to write the text and minerals to create its pigments, consistent with materials used during the early 15th century. Together, these results strongly suggest that the manuscript is not a modern forgery.

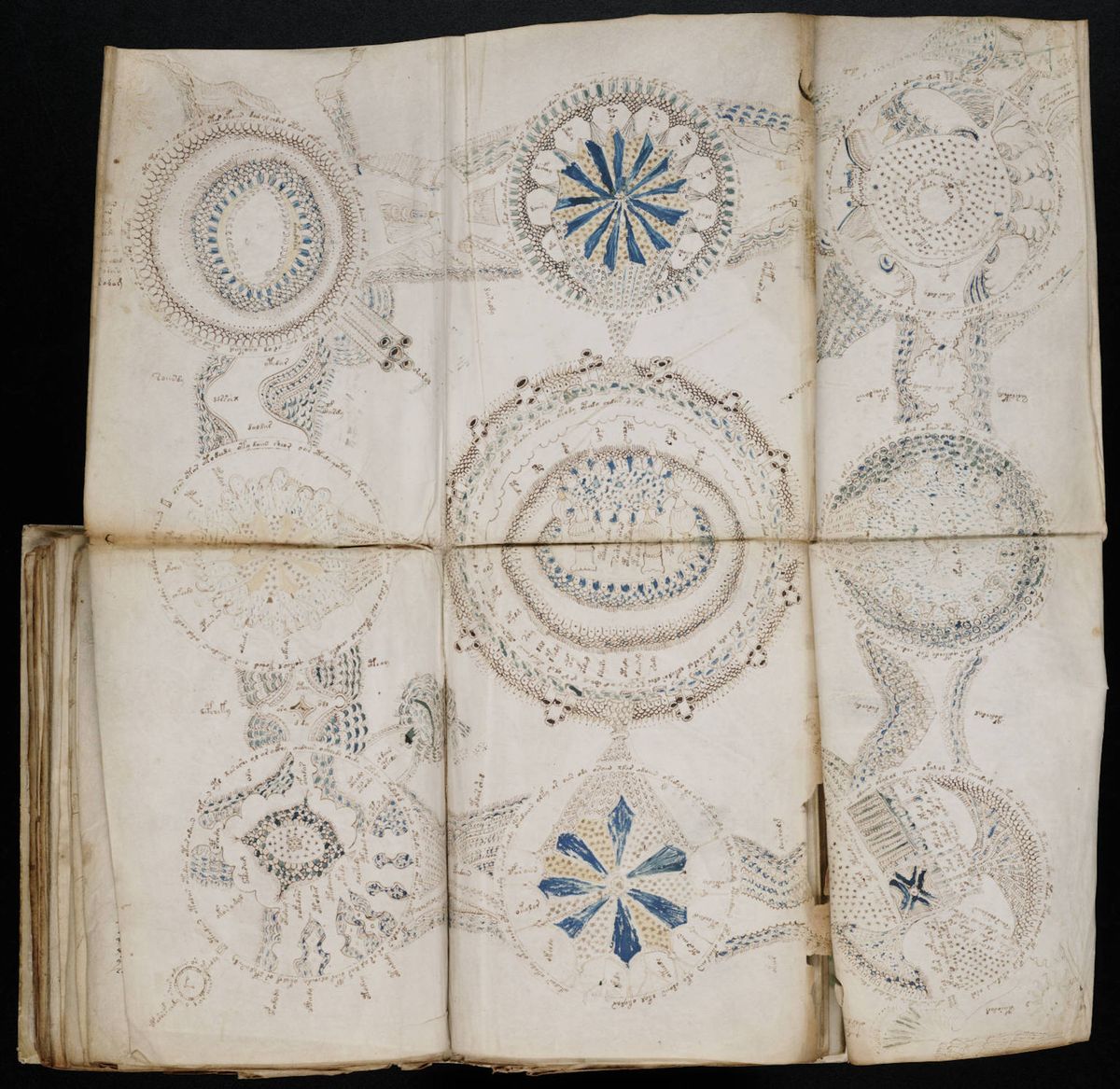

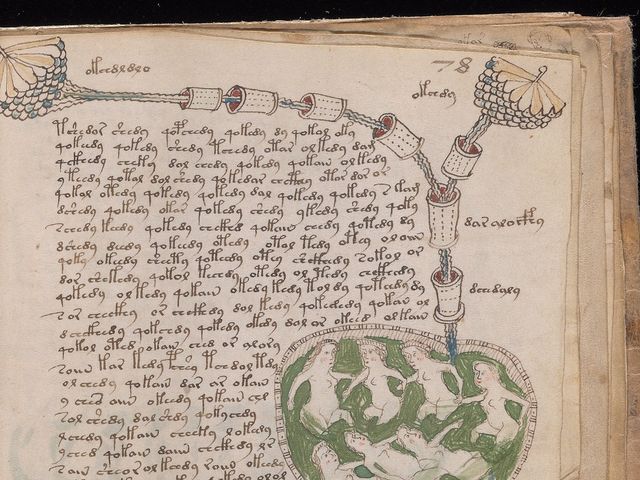

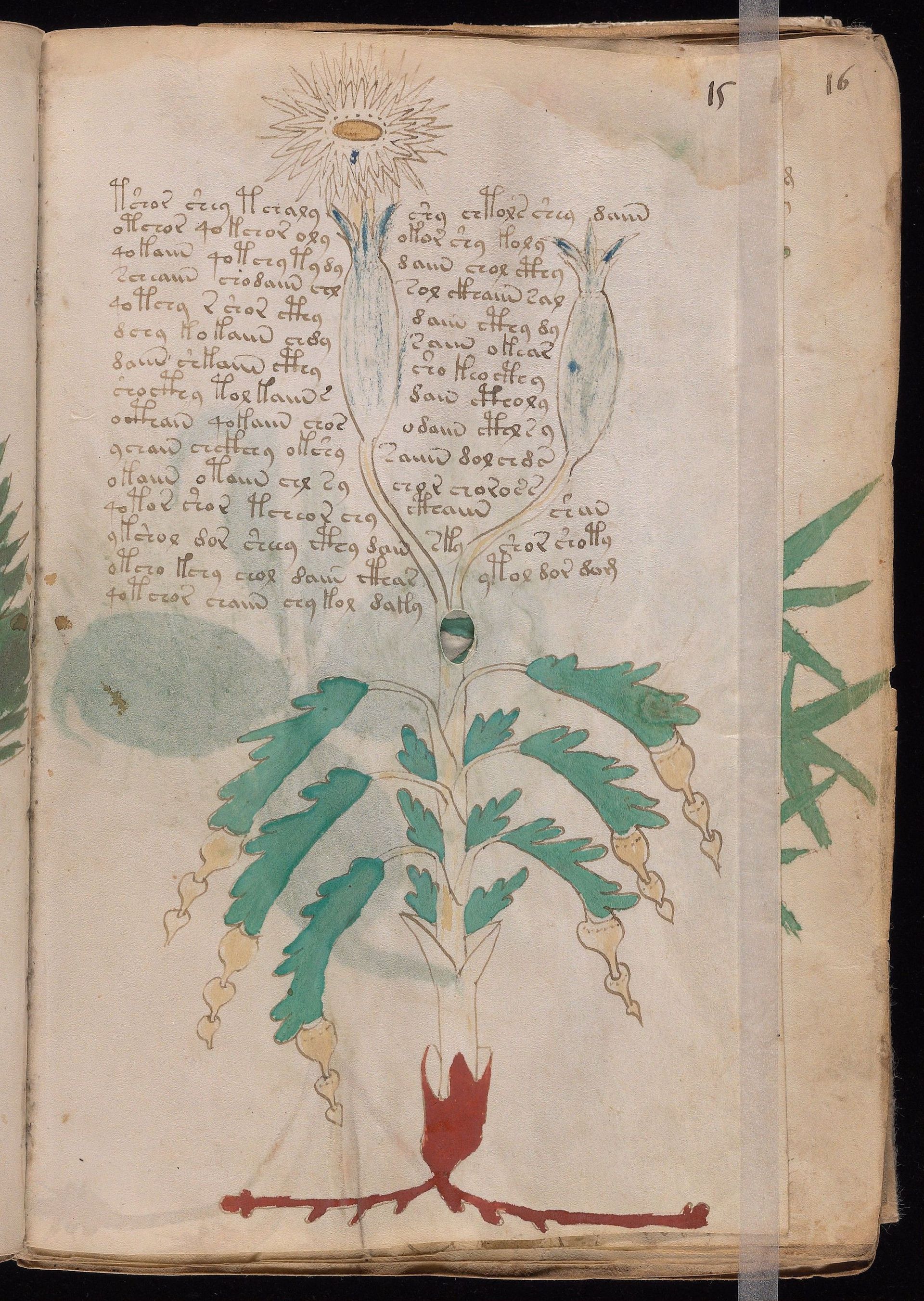

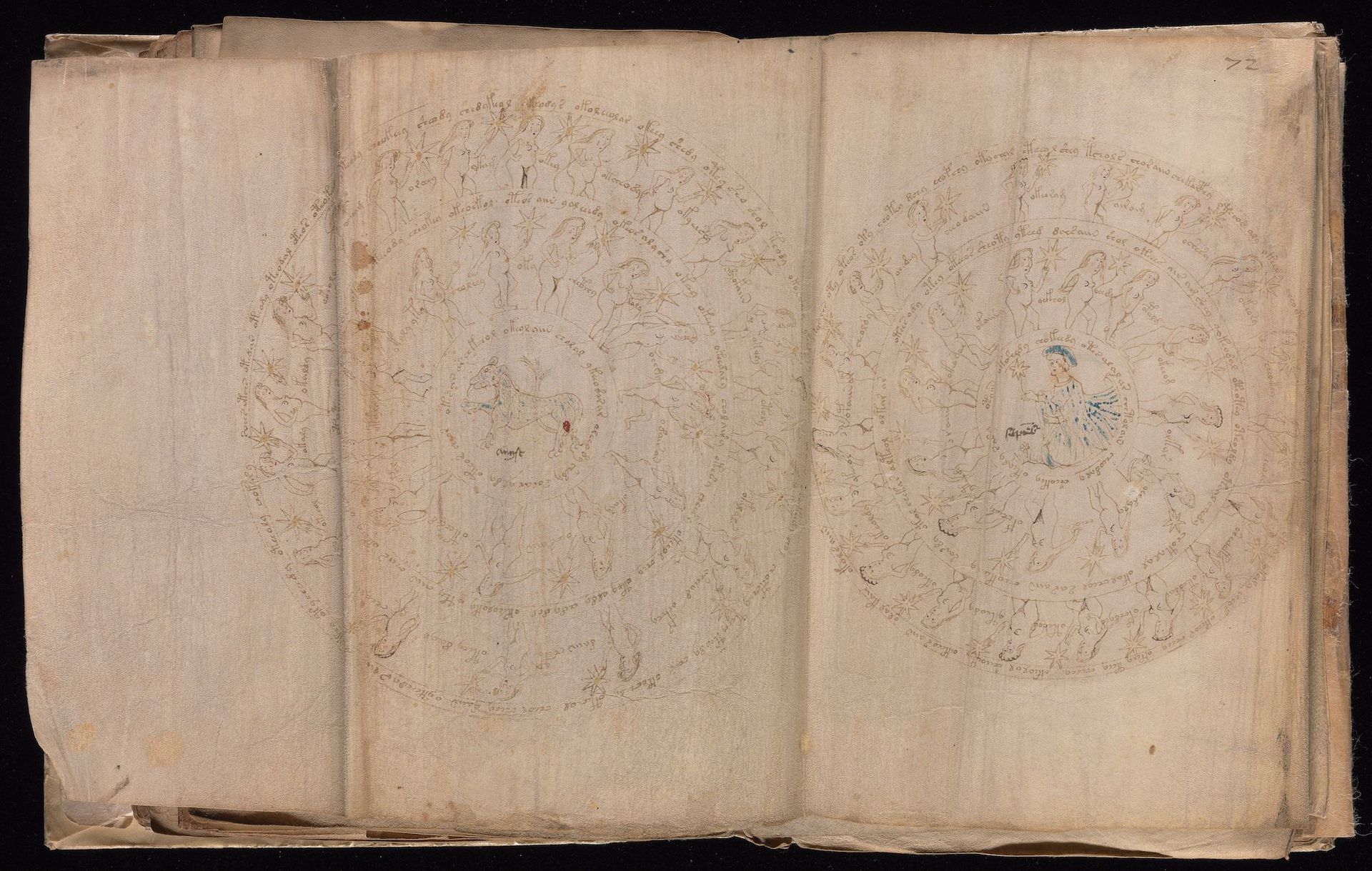

Throughout the manuscript’s 234 pages—a number of extra pages are now missing—there are colourful illustrations of plants and herbs, Zodiac symbols, bathing women, strange tubes, a dragon and a castle, among other imagery. Taking these together, historians have divided its content into six categories: botanical, astronomical and astrological, biological or balneological (bathing to help ease health problems), cosmological, pharmaceutical and recipes. Meanwhile, statistical analyses of the manuscript’s unique script have concluded that its content is not gibberish, and a recent study of the handwriting has shown that the text is the work of five scribes, writing in at least two dialects. It appears, then, that a real language hides behind the symbols.

A spread from the Voynich Manuscript Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

Much of the manuscript’s history can be reconstructed too. Its earliest named owner appears to have been the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II in Prague, who bought it from an unnamed individual for 600 ducats. As Rudolf lived from 1552 to 1612, this leaves at least a century of the manuscript’s earlier ownership missing. From Rudolf, the manuscript passed to the court pharmacist Jacobus Horcicky de Tepenecz, who wrote his name on the inside, and then, via other hands, to Johannes Marcus Marci, a royal doctor and scientist. In 1665 or 1666, Marci sent the manuscript from Prague to the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher in Rome, hoping that Kircher could crack its code. It then remained in the possession of the Jesuits until Voynich bought it.

The mysteries

Where the Voynich Manuscript was created remains unknown—Yale University’s library catalogue cautiously suggests “Central Europe [?]” as its place of publication—and we still can’t read its unique script or identify which language it hides. William Romaine Newbold, a philosophy professor at the University of Pennsylvania, made the first attempt to solve this problem in the 1920s. He attributed the manuscript to Roger Bacon, the famous 13th century Franciscan friar and philosopher, and argued that tiny Latin letters formed each Voynich symbol. His theory was discredited within a few years of its publication.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

Little has changed since Newbold’s time—solutions appear with great regularity and are just as quickly dismissed by scholars. Over the years, suggestions for the hidden language have included a medieval North Germanic dialect, the Aztec language Nahuatl, Latin and Proto-Romance. Most recently, in 2020, the Egyptologist Rainer Hannig concluded that the language is based on Hebrew. Researchers have also tried to identify the plants shown in the illustrations, with some arguing that they represent species known from the Aztec world. Yet, until someone fully and incontrovertibly translates the manuscript’s text, none of these theories can be proven.

Unsurprisingly, then, with so much unknown, the Voynich Manuscript’s purpose is impossible to determine with certainty. For now, the best guess is that it’s a work of medical, magical or scientific thought, but our understanding could change—scholarly investigations are ongoing and continue to reveal new clues.

An online conference will be held by the University of Malta from 30 November to 1 December, bringing together Voynich experts from across the globe. After centuries of silence, perhaps the Voynich Manuscript will finally reveal its secrets.

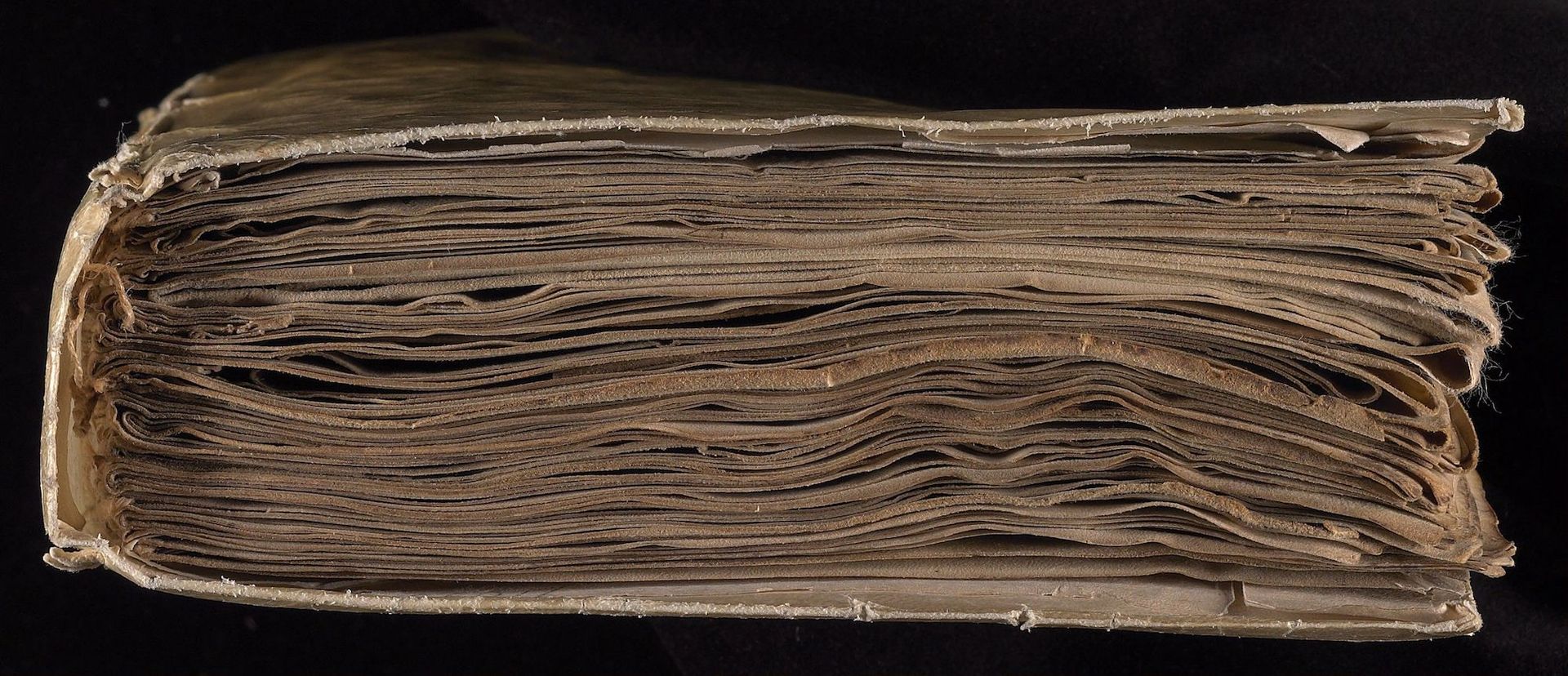

The top or head of the Voynich Manuscript Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut