The Jubilee decorations have been taken down across the UK and the queen has retired to Balmoral for a well-deserved holiday. But now the thoughts of some of the royal household must be turning to a more sensitive subject: the coronation of her successor. One imagines the retrieval of dusty files and discreet conversations in gentlemen’s clubs on Saint James’s. One ancient tradition that might make the royal mandarins pause over their soup relates to a tapestry with a graphic depiction of The Circumcision of Isaac.

Thanks to a detailed late 17th-century account by Francis Sandford, we know that this was hung beside the throne in Westminster Abbey for the coronation of James II and circumstantial evidence indicates that this usage followed earlier practice. Whether royal sensibilities would embrace such a conjunction when Prince Charles is crowned remains to be seen, but it would certainly be an atmospheric evocation of ancient traditions, when lavish textiles and tapestries provided the staging for all such court ceremonies. And, having waited 73 years and counting to succeed his mother, it might be nice for Charles to be flanked by an image of someone who, according to Genesis, lived to the fine age of 180!

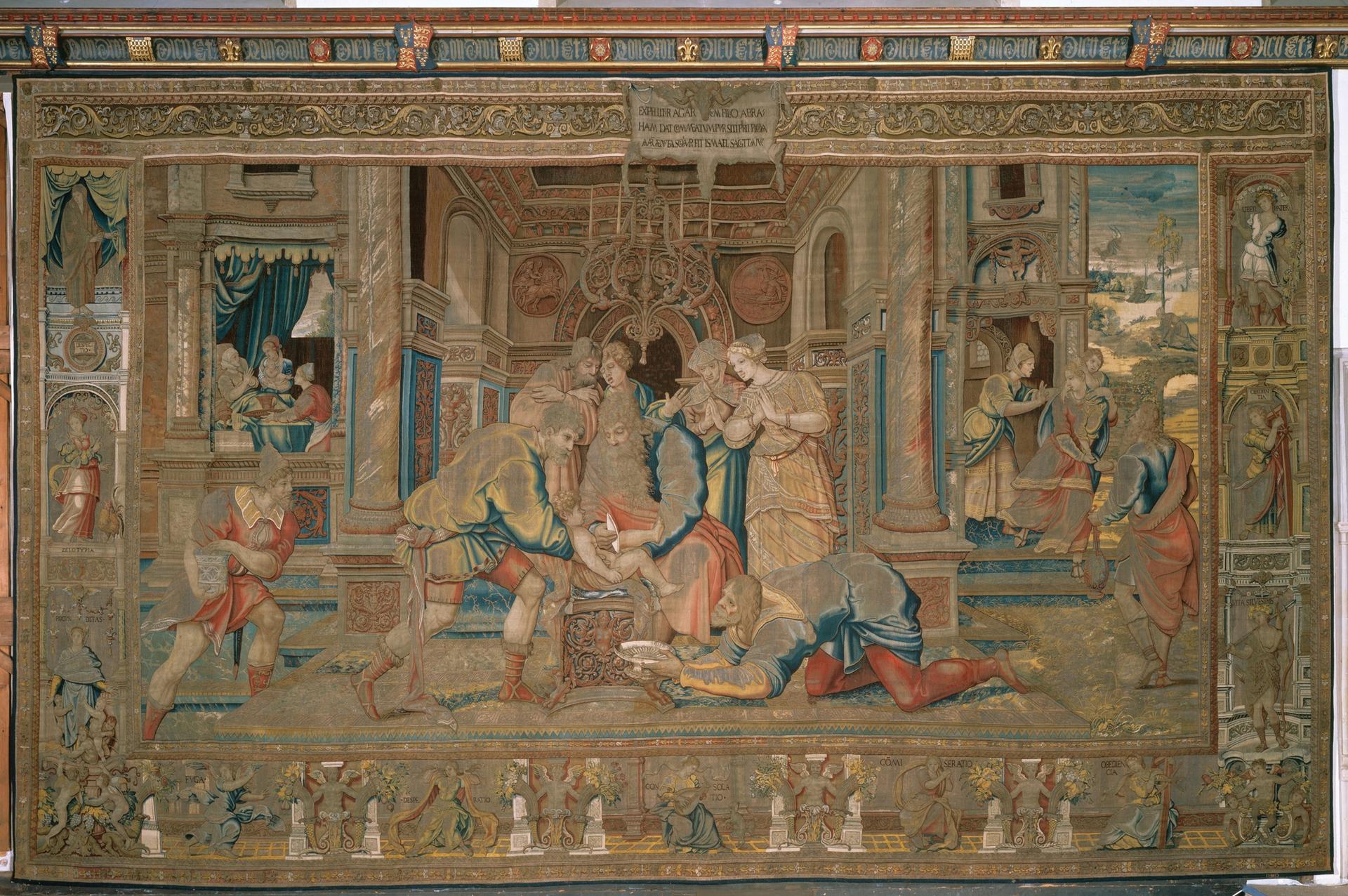

The Circumcision of Isaac is from the ten-piece tapestry set of the Story of Abraham that Henry VIII purchased in the early 1540s and that, remarkably, survives in entirety at Hampton Court. Lavishly woven with masses of gilt thread and with a total length of more than 80m, the ensemble is the most impressive tapestry set to survive in Britain.

Historically, such valuable textiles were only hung for special events, but such husbandry was abandoned when tapestries went out of style in the 18th century, with the consequence that the Abraham tapestries, like so many others, are now faded and their gilt thread tarnished. Nonetheless, they still make for an imposing display in the great hall, dappled with motes of coloured light from the stained-glass windows.

Heads up: the Imperial State Crown sits on a cushion at the state opening of Parliament in May; it will sit on Prince Charles’s head when he succeeds the Queen Hannah McKay; Reuters/Alamy Stock Photo

The set was the most expensive that Henry purchased during his reign, and that is saying something—the inventory of royal goods taken after his death lists more than 2,500 tapestries of varying qualities and ages. Based on the cost of other such gold woven tapestries at the time, we can estimate that it must have cost at least £2,000, at a time when eminent court artists such as Holbein were paid annual salaries of £30 and a few pounds more for each painting.

Heart of the Reformation

Why would Henry have spent so much money on a set of tapestries depicting Abraham? The answer takes us to the heart of the English Reformation and the steps that Henry and his advisers had taken to consolidate his standing as the head of the English church. As every British schoolchild knows, the pivotal drama of Henry’s life hinged on his desire to produce a male heir. Katherine of Aragon failed him in that respect, producing only Princess Mary, and some time in the mid 1520s, Henry decided on divorce so that he could marry Anne Boleyn, a conflation of desire and duty that was to change the course of British history. In the face of vehement opposition from the papacy, Henry broke with Rome and declared himself the head of the English church, arguing that ancient precedent defined Britain as an empire and the British king as independent from any other worldly jurisdiction.

As the conflict with Rome intensified, legalistic arguments were augmented with a more personalised form of identification between Henry and the Old Testament patriarchs. Henry was a second Ezekiel, sent from heaven to reform abuses; a modern King David, delivering England from Goliath, the pope; a second Moses, leading England, a new Israel, out of bondage. Works of art produced for Henry during the late 1530s portray patriarchs such as Solomon and David with the King’s features. The cover plate of the Great Bible published in 1539 goes one step further, portraying Henry in direct communication with God and then disseminating the Bible, quite literally a prophet and apostle to his own people.

An illustration from Francis Sandford’s The History of the Coronation of James II (1687) depicts The Circumcision of Isaac next to the coronation throne Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and the Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1943

The notion that Henry was the nation’s patriarch was reinforced in court ceremony by the ubiquitous display of tapestries depicting Old Testament forebears, some inherited, but mostly new acquisitions. The finest were made in Brussels and while the local artists and weavers could not produce overtly propagandistic images for Henry because of close scrutiny by agents of Charles V—several leading weavers and artists were prosecuted for heresy during the late 1520s—there was nothing to stop Henry purchasing sets that depicted old testament patriarchs.

Abraham, the founder of the Hebrew nation and first of the great patriarchs, was the Old Testament model most resonant for Henry as he sought to establish a new Church of England centred on the Tudor dynasty. The Abrahamic analogy would have been additionally appealing after 1537 because, with the birth of Prince Edward, Henry finally had an heir, just as Genesis established Abraham’s undisputed succession of his house through Isaac.

While no documentation for the conception and order of the set survives, we know it was delivered to the English court sometime between September 1543 and September 1544. A set of this size and fineness would have taken at least two years to weave, possibly more, so the designs and cartoons—attributed to the workshop of Pieter Coecke van Aelst, the leading tapestry designer of the time—must have been conceived some three to four years earlier, that is, when Prince Edward was in his infancy.

The borders of the Abraham tapestries expand the analogy between the old testament patriarch and his modern-day successor, featuring more than 100 allegorical figures. These provide a running commentary on the scenes depicted within the tapestry, expanding the analogies between Abraham and Henry, Isaac and Edward into a broader affirmation of the moral values embodied by the Tudor kingship. In sum, the tapestries provided a vast speculum principis—a mirror for princes—that would have been readily understandable to everyone in Henry’s circles.

The Circumcision of Isaac, from the Story of Abraham series of tapestries (1540-43) by Pieter Coecke van Aelst might be considered too explicit, but it made an appearance at James II’s coronation Courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

For what forum was the Abraham set intended? It was first inventoried at Hampton Court in 1547 along with some of Henry’s other most expensive tapestry purchases, and it has remained there ever since. Hampton Court was undergoing major development during the late 1530s and early 1540s and the tapestries could well have been intended to hang in the great hall and subsequent audience chambers. That said, considering the phenomenal quality and volume of gold thread in the tapestries, it is possible that from the start Henry had a second and grander venue in mind: Westminster Abbey where, sooner or later, his long-awaited heir would be crowned as his successor.

Threads of history

While records of the tapestries utilised at the coronations of Edward, Mary, Elizabeth I and Charles I are lacking, we do know that Westminster was adorned with scenes from Genesis for the coronation of Elizabeth. During Charles’s reign, the Lord Chamberlain’s office was ordered to investigate the traditions surrounding royal ceremonies. And at Charles II’s coronation, four Abraham tapestries, which duplicate those at Hampton Court, were purchased for use at the coronation (whether the originals were also used is unclear). Thus, the use of the Abraham tapestries at Westminster Abbey for the coronation of James II seems to have been based on historical precedent. The selection of The Circumcision of Isaac to flank the high altar was no coincidence. The circumcision was the physical manifestation of God’s covenant with Abraham and the continuation of his house through the line of Isaac. What more resonant a scene for the transition from one monarch to another, and the continuation of the blood line?

When I recently inquired with the Royal Collection as to the condition of The Circumcision of Isaac tapestry in the hope of borrowing it for the Tudor exhibition that will take place in New York, Cleveland and San Francisco next year, I was told that it was too fragile to travel. But one might hope that the royal coronation would elicit a more positive response. It would be a fine resurrection of long-standing tradition, and resonant reminder of the intertwined origins of the royal succession and the Church of England, if this same tapestry were to be ready for use, once again, when the time honoured-words are soberly proclaimed: “The Queen is dead, long live the King.”

• Thomas P. Campbell, director of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (and formerly of the Met), and author of Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty, Yale, 2007