For more than four decades, Henry Darger created hundreds of watercolours, pencil drawings, collages and more in his small Chicago apartment, envisioning his own world through storybook-like scenes of adolescents, ridden with violence. It was only after his death in 1972, at the age of 81, that the lifelong recluse became one of the world’s most well-known outsider artists.

Now his archives are at the centre of a legal battle between his distant relatives and his former landlords, who saved Darger’s art upon his death and promoted it through exhibitions, publications and sales. A case filed 27 July in US District Court by the Darger estate accuses Kiyoko Lerner and the estate of her husband, Nathan Lerner, of exploiting the artist’s “unpublished and copyrighted artwork” and seeks to name the Darger estate as the sole and exclusive owner of all works and copyrights. The complaint alleges that the Lerners used Darger’s legacy to generate “tens of hundreds of millions of dollars”.

“Defendants’ acts are willful with the deliberate intent to cause confusion and deception in the marketplace, and deprive the Estate of control of the Darger Works, and tangible personal property, and associated revenue that is rightfully the Estate’s,” the court papers read.

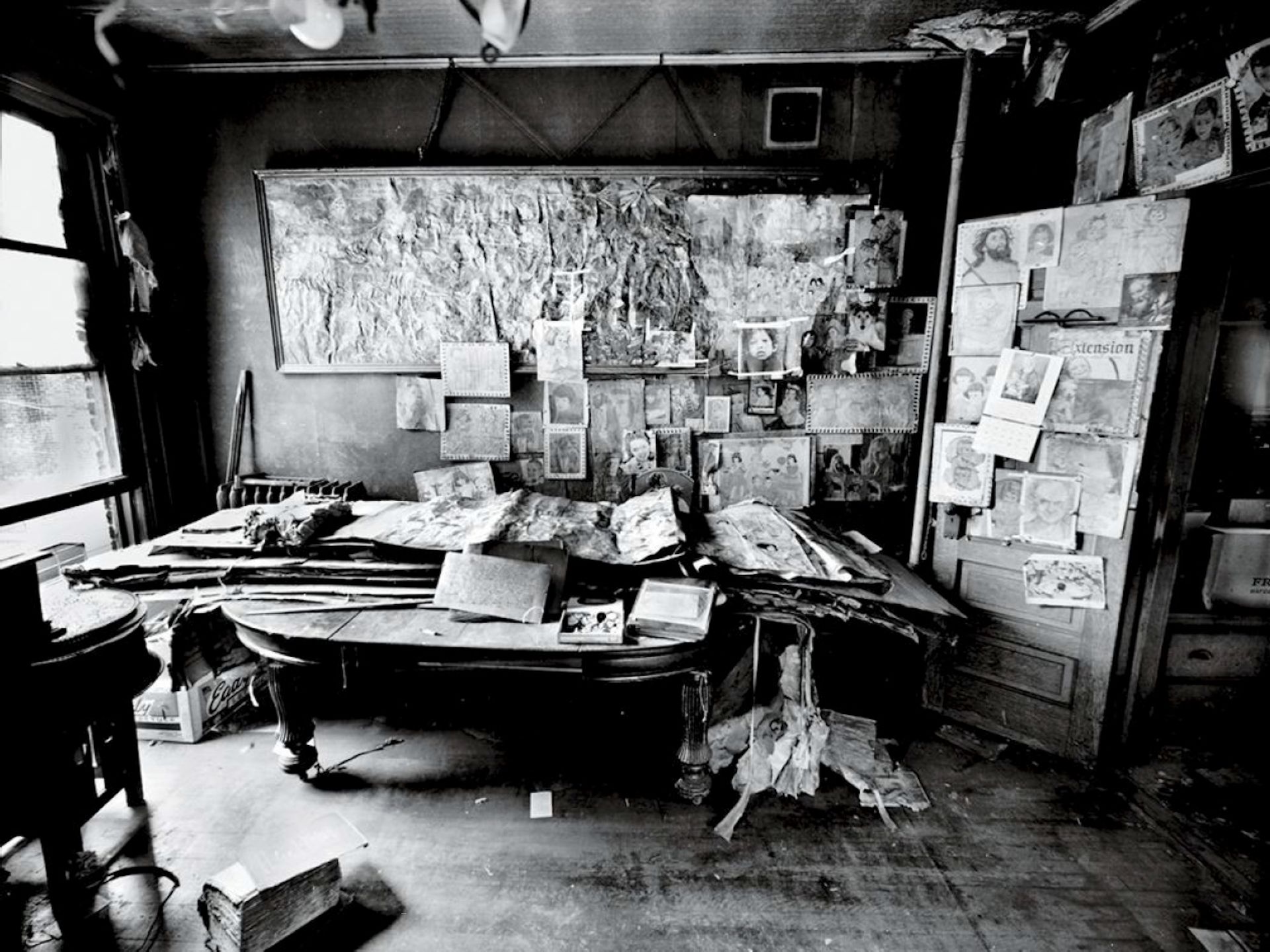

The Lerners were Darger’s landlords from the late 1950s to 1973, when Darger moved to a care facility due to medical issues. Upon his death in April of that year, the Lerners entered his former apartment to clear it out and discovered a trove of artworks amid stacks of newspapers, notebooks and other paper ephemera. They began promoting the work, although Darger had allegedly told Nathan Lerner to “throw everything away”, as Kiyoko Lerner recalled in a blog post. “Nathan felt that Henry’s soul was still in the room and he could not destroy it,” she wrote.

A room in Henry Darger's Chicago apartment as it appeared shortly before his death in 1973 Via court documents

The couple worked with the Hyde Park Art Center to mount Darger’s first exhibition in 1977. Over the years, he gradually rose to art-world fame, with his posthumous inclusion in institutions from the Museum of Modern Art to the American Folk Art Museum. In Chicago, a replica of Darger’s room is on permanent display at Intuit: The Center of Intuitive and Outsider Art, its contents donated by Kiyoko Lerner.

The fight over the rightful ownership of Darger’s work first reached the courts when a group of 50 or so people claiming to be his relatives filed “petition for determination of heirship” in an Illinois probate court last January. According to The New York Times, Chicago collector Ron Slattery had tracked down several descendents and raised to them the question about rights, believing that family should manage an artist’s estate. Most are first cousins twice or three times removed.

Last week’s suit follows a key decision made 2 June by the probate division of a Cook County court that named Christen Sadowski, a Darger relative, the supervised administrator of the artist’s estate. The complaint notes that Sadowski is “authorised to take possession of and collect the assets of the Estate, including its copyright and personal property interests”. These assets include significant Darger works such as In the Realms of the Unreal, a 15,000-page illustrated narrative of a disturbing fantasy world of girls fighting abusive adults. The suit also asserts that “copyright interests do not transfer with the tangible and material art objects or literary objects. Any claim of ownership in the copyright interests to the Darger Works [that] Lerner asserts is, therefore, invalid and unenforceable, as well as the alleged transfer of the tangible personal property, which is an asset of the Estate”.

In addition to seeking a binding judgement that the Darger estate is the sole and exclusive owner of the copyright of Darger works, the heirs are asking to be awarded damages and the defendants’ profits, as well as the transfer of the domain for the officialhenrydarger.com website, which the Lerners operate.

Still, others argue that Darger’s international renown would not have been possible were it not for the Lerners, who went to great lengths to preserve not only his art but also his manuscripts. “Most landlords would have been, ‘Let’s rent the room, get out the dumpster,’” the dealer Andrew Edlin, who has represented the estate of Darger since 2006, tells The New York Times. “Nathan Lerner spent 25 years protecting his legacy. If not for him, we would never know about Darger.”