At this year’s Venice Biennale, one of the outstanding installations is Precious Okoyomon’s contribution to Cecilia Alemani’s main exhibition, The Milk of Dreams (until 27 November). It is occupied by totemic figures made in raw wool, yarn, blood and dirt, surrounded by vegetation—sugar cane and the invasive, entangling presence of Japanese kudzu, a plant brought to the American South to try to heal the damage to the soil caused by the over-cultivation of cotton. It is a symbolic landscape, a reflection on enslaved and displaced peoples, and their deep connection to land and environment.

It builds on an earlier work by Okoyomon, developed for the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt in 2020, where the kudzu eventually consumed the wool figures. That work was called Earthseed and it took its title directly from the new religion formed by Lauren Olamina, the visionary Los Angeles teenager at the heart of Octavia E. Butler’s 1993 novel Parable of the Sower (and its 1998 sequel, Parable of the Talents) in which Olamina struggles to survive and then build a new community in mid-2020s US. It is a place where civil society has largely collapsed after being ravaged by climate change and succumbing to a political zealot as president, who promises to Make America Great Again.

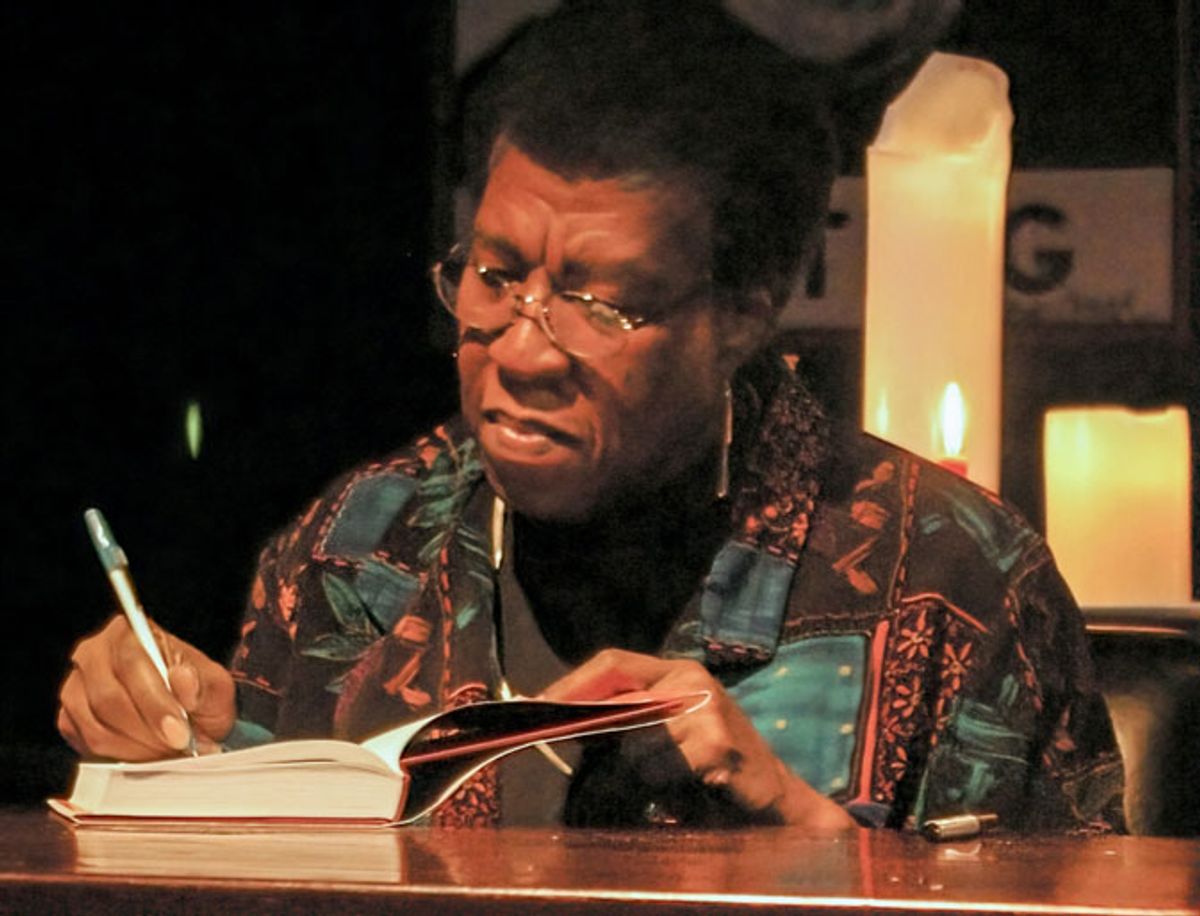

Butler, who died aged just 59 in 2006, created speculative fiction that ingeniously reflects on historic and contemporary inequities and forms of activism, from civil rights to feminism. Her wide-ranging novels, written over 30 years, veer from so-called “soft” or social science fiction like the brutal and brilliant 1979 masterpiece Kindred—where a 1970s writer travels back in time to 19th-century Maryland to intervene in the life of a slave-owner ancestor—to works that get closer to classic space-opera fantasy, like the Xenogenesis series, about human-alien civilisations formed after a nuclear apocalypse. Though she was the first writer in her genre to win a MacArthur Genius grant, and is regarded as among sci-fi’s greatest exponents, Butler was ambivalent about being pigeonholed. “I write about people who do extraordinary things. It just turned out it was called science fiction,” she said.

That Okoyomon chose to title her landmark project after Butler’s idea of Earthseed reflects the growing influence of the Pasadena-born writer among artists. Also in 2020, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, the painter Toyin Ojih Odutola—whose dynamic graphic work you could imagine illustrating Butler’s stories—wrote about Earthseed and Parable of the Sower for the gallerist Jack Shainman’s online social and racial justice platform, States of Being. “The speculative has always been my go-to in times such as these,” Odutola wrote, adding later that Butler’s words in Parable of the Sower “illustrate through Lauren’s fictional autobiography what resilience looks like: the day-to-day toil to build a new way of living—of seeing and becoming”. She also quoted Butler’s contention that sci-fi allowed her to explore “any aspect of humanity or the universe around us”.

This imaginative freedom is key to explaining why Butler’s oeuvre is hitting home with countless, enormously diverse, artists. For the Turner Prize-shortlisted Sin Wai Kin, who uses drag to explore gender identity and racial injustice, Butler’s kind of speculative fiction has been crucial in finding ways to imagine “what a better world looks like, and how it functions. So, in this way, it functions like drag, in that it’s a way of taking yourself out—for science fiction, out of your environmental and social context, and for drag, out of your bodily context.”

Alberta Whittle, who is representing Scotland at the Biennale, quotes directly from Parable of the Sower in her climate-justice themed video installation From the Forest to the Concrete (to the Forest) (2019), and draws on the notion of “hyperempathy”, the fictional (and deeply metaphorical) congenital disease that Lauren Olamina must bear in the Parable series, where she physically feels the pain and pleasure experienced by those around her. Among the artists who have long looked to Butler is Isaac Julien, whose video work Encore II (Radioactive) (2004) is directly inspired by Lilith Iyapo, the cyborg protagonist in Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy (now known as Lilith’s Brood), intertwined with references to the African American explorer Matthew Henson. Butler’s interspecies beings also helped the sculptor Francis Upritchard imagine her distinctive multi-limbed figures, fused with historic Asian gods, among other things.

Candice Breitz, the South African artist, said in a conversation for The Art Newspaper’s podcast A brush with… that she returned to Butler’s feminist science fiction “quite specifically” in relation to Labour (2019), a video piece in which she imagines infants who would grow up to be totalitarian rulers being sucked back into their mothers’ wombs. Breitz lauds Butler’s “ability to use a future language to describe the present, and the exquisite balance in her writing between observation of lived realities that aren't going away anytime soon— oppressions and hardnesses that are very real and very now—but then the way in which she reflects on them through constructions of possible utopian futures, which sometimes slip into dystopia. And, of course, the very powerful feminist messaging that resonates throughout her work.”

As Odutola puts it, “Butler’s virtuosity collates a variety of interests”. Through them, she liberates artists to do the same; probing the past, responding to the present and imagining possible futures.