Through the best works of her career, Barbara Kruger has been an incisive cultural critic, one blessed with arch graphic design skills and a wry sense of humour. In the 1980s, she made collages anticipating the meme as a dominant form of contemporary culture and understood going viral before the invention of the phrase.

In Untitled (No Comment) (2020), a nine-minute-and-25-second video work on view now at David Zwirner in New York, certain moments come close to doing what the artist does best—that is, they put words to images in a way that sparks a little tension, or a dose of irony. In the same way that her early paste-ups assumed the popular media format of their day, this montage of audio and video clips invokes the popular media of the present. Snapshots of cats in toilet bowls, the wedding footage of strangers and sound bites of Kardashian commentary are layered and stitched together, echoing with the absurdity of millennial-aged advertising and the rapid-fire content barrage of the internet.

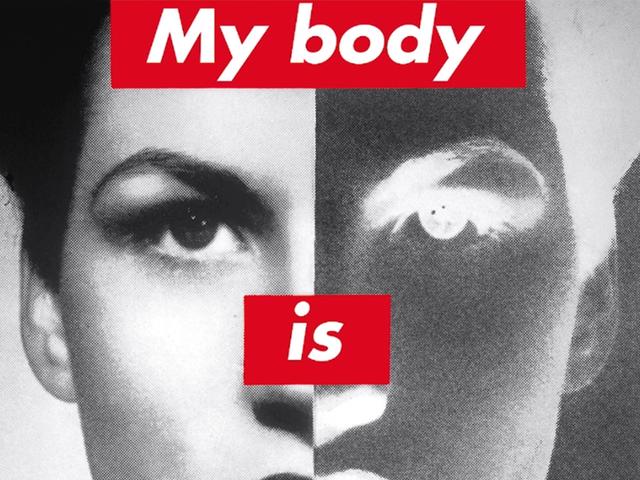

The rest of Kruger’s survey at Zwirner, however, engages mainly with the past, revisiting and remixing her greatest hits. Early icons like Untitled (Your body is a battleground) (1989) and Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am) (1987) are resurrected as freestanding LED screens, animated with special effects. The words change to the clicking sounds of a typewriter—“I need therefore I shop”, “I love therefore I need”—before collapsing into a pile of puzzle pieces. It is a digital repackaging that does very little to improve upon classic works, but it does add an air of novelty, a new format in which to sell them. (I think of this as the gift shop phase of an artist’s career.)

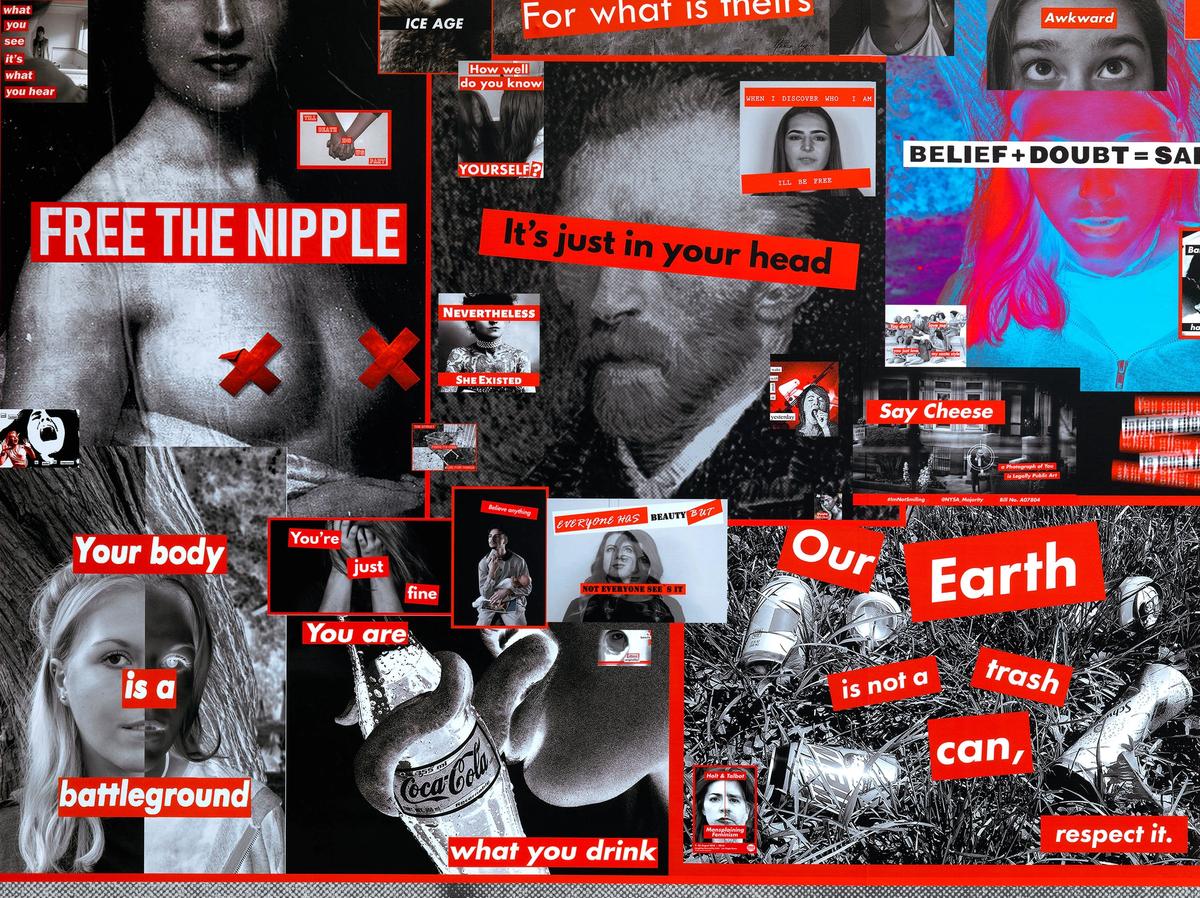

Like a shrine to the enduring appeal of her relentlessly copied branding, the latter work stands in a gallery wallpapered with various Kruger knock-offs—amateurish memes and fliers that have appropriated her familiar red bands and white sans-serif typefaces, dragged and dropped into new collages that look worse than their constituent parts. Scored by the animation’s rhythmic clicking, this room seems to imply that an infinite number of monkeys at typewriters could not reproduce the perfect synthesis of word and image of Kruger’s early works. Alternatively, perhaps, she assumed we are no longer reading what she is writing very closely.

Installation view, Barbara Kruger, David Zwirner, New York, 2022. Courtesy David Zwirner.

The groundbreaking feature of Kruger’s early work is the way her words functioned as an extension of her gaze. When her razor-sharp vision sliced through the veneer of the visual landscape, her aphorisms spelled out the shameful truths lying below the surface. The imagery eventually gave way to text-only work—colossal room wraps, murals, MetroCards, skateparks—and as her one-liners grew larger and longer, they began to say less. Texts projected onto Zwirner’s walls hold the reader’s attention and control the pace of their engagement by unfolding word by word. Animated with redactions, rhyming replacements and annotations, they ultimately do not amount to the tightly crafted insights on American exceptionalism and language that they purport to be, instead functioning as protracted musings on the words “post,” “you”, “I” and “this”.

At the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), a concurrent immersive Kruger experience fills the museum’s central atrium with alternating black and white bands of text, drawn from a repertoire of stock phrases recycled from other bodies of work: “Money talks”, for example, or “The moment when pride becomes contempt”. It’s sometimes difficult to discern what is intended to be facetious from what is meant to be read as sentimental. According to one wall, “This is about loving and longing”—but what about living and laughing?

Installation view of Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You., on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2022-2023. Photo: Emile Askey.

Kruger is rightly lauded as one of the most influential living figures in visual culture, both in popular culture and in fine art. Wrongly, she’s also been designated the art world’s moral compass. In May, in response to the leaked Supreme Court opinion overturning Roe v. Wade, the artist debuted a new work in the New York Times opinion pages. In alternating black-on-white and white-on black text, it read, “IF THE END OF ROE IS A SHOCK, THEN YOU HAVEN’T BEEN PAYING ATTENTION”, a phrase that lags a few beats behind Jenny Holzer’s expertly crafted “Abuse of power comes as no surprise”. It was widely shared but seemingly poorly understood.

In the fine print, Kruger blamed a “lack of strategic voting and thinking” for the current composition of the Supreme Court, rather than the structural flaws that corrupt the American electoral process; the inaction of corporate Democrats already in office or the ineffective media culture that she was once so adept at dissecting. The Times piece operated in the opposite way of how her art allegedly works: not as a provocation or speaking truth to power, but as reassurance to the art-consuming class. As a digital bumper sticker, it provided a way of marking oneself present in the moment, specifically to fellow members of the art world.

It felt like the continuation of a long-running mistake—a product of critical nostalgia, projection and hyperbole—for the art world to turn to Kruger as its most trusted brand of political commentary. “I never say I do political art, nor do I do feminist art,” Kruger told Interview in 2013. “I’m a woman who’s a feminist, who makes art.”

In 2020, when images of protestors being arrested in front of Kruger’s murals in Los Angeles flooded the news, the difference between art and activism should have been abundantly clear. The activists were the ones in handcuffs, the artist was arguably the cameraman who captured the footage. And those of us who cannot tell the difference (alongside the city’s law enforcement) make up, to borrow another Kruger-ism, the remaining “ridiculous clusterfuck of totally uncool jokers”.

- Barbara Kruger, until 12 August at David Zwirner, New York

- Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You., until 2 January 2023 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York