The group exhibition Women at War at Fridman Gallery in New York includes the work of 12 artists who either live under war in their nation or have fled to different parts of Europe as refugees. The curator Monika Fabijanska was initially hesitant about keeping artists busy with preparations for the show, but long conversations revealed that art could be helpful and healing in dire situations.

“Logistics of a show could add to the fear and exhaustion that they had to go through,” the Polish-American curator told The Art Newspaper. “But it became clear that making art and thinking about it provided another contact with life—a framing deadline or putting final touches to a work provided them a distraction.”

Fabijanska has previously organised exhibitions that also touched upon harsh topics, such as rape in the 2018 exhibition The Un-Heroic Act at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. But with this exhibition she felt the incomparable reality of an ongoing war. Practical challenges such as days-long pauses in artists’ email conversations or difficulties with shipping were eventually solved, but the trauma she witnessed in her community prevailed.

Fabijanska made a preliminary wish list with three artworks by each artist and researched which one in the trio would be available to loan. “This is the first time I brought together artists before getting to know them,” she says. “But we have built deep relationships after months of communication and sharing.”

Except a 1963 linocut portrait of poet Ivan Svetlichny by Alla Horska who was blacklisted for her political art and was presumably murdered by the KGB in 1970, the show’s paintings, drawings, photographs and videos are from the last eight years since the Russian invasion started in Crimea and Donbas. In fact, underlining the war as an ongoing crisis, rather than a recent case, is a crucial aspect of the project.

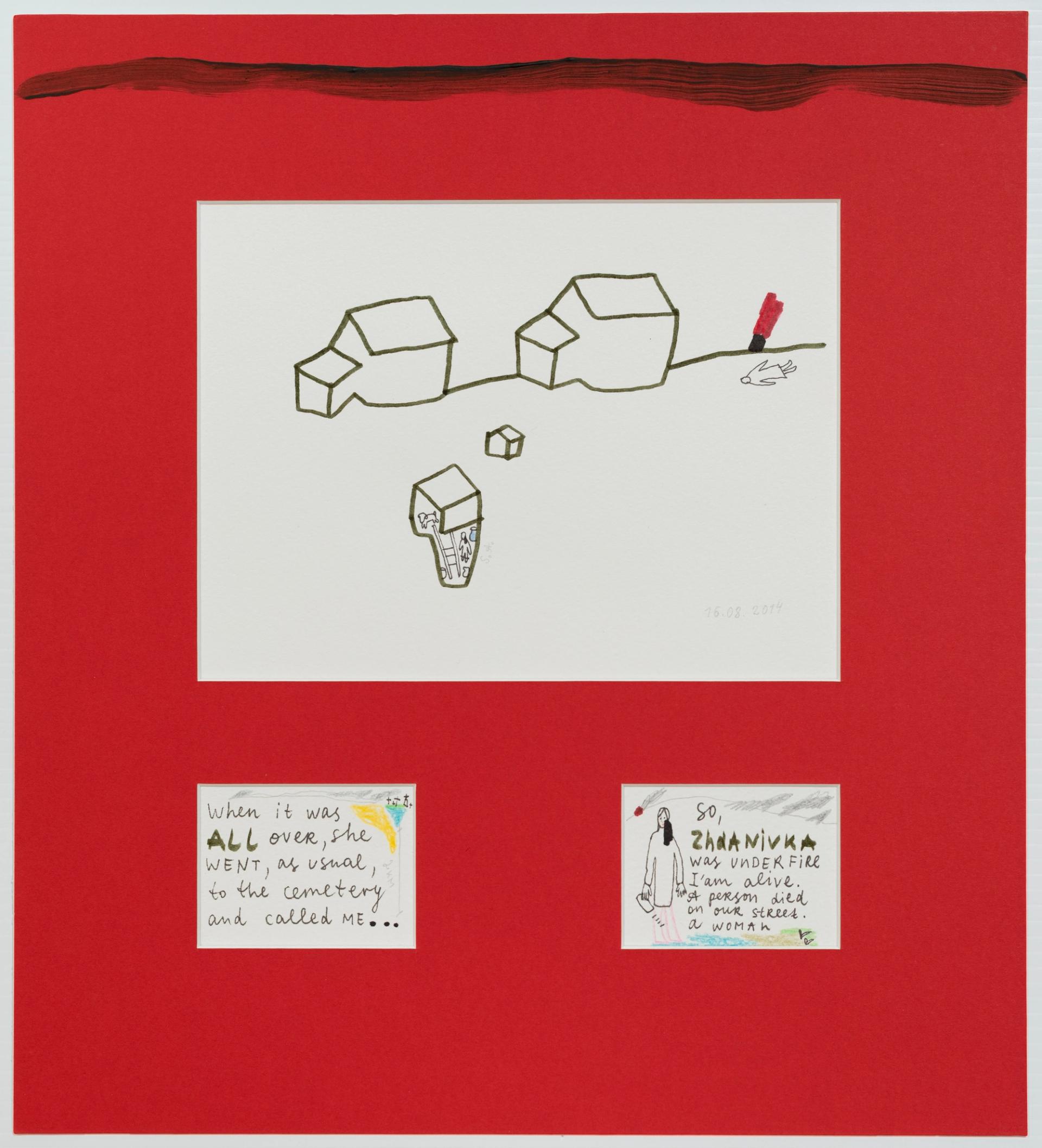

Some highlights of the show include the 10-drawing series Strawberry Andreevna (2014-19) by the artist Alevtina Kakhidze, who still lives near Kyiv. The work conveys the heartbreaking story of her mother who remained in Donbas during the invasion and traveled to the local cemetery every day to have phone service to call Kakhidze. The final drawing depicts the mother’s death due to heart attack on her way to collect pension. “I still feel the emotion of knowing I would fly back to New York with Alevtina’s drawings the next day, and she back to Ukraine,” Fabijanska says.

Alevtina Kakhidze, Strawberry Andreevna #4 (2014). © Alevtina Kakhidze. Courtesy of the artist.

Hope, however, also flourishes in the artists’ stories. Lesia Khomenko’s life-size painting Max in the Army (2022) depicts her sound artist partner Max Robotov, who is currently enlisted, like many Ukrainian men. With emphasis on the soldier’s sharp expression and hefty uniform, the painting is a brisk illustration of longing and anticipation, which somewhat found the couple few weeks ago when Khomenko traveled to Budapest from New Jersey and met her new husband—the marriage took place via Zoom—after a 10-hour bus ride to the Ukrainian border.

The gallery’s founder Ilya Fridman invited Kyiv’s Voloshyn Gallery, which also represents the show’s two artists, Khomenko and Zhanna Kadyrova, to collaborate on the show while the gallery currently remains nomadic due to war. After a pop-up in Miami, Voloshyn will participate this September in the Armory Show with a two-person booth for Khomenko and Nikita Kadan.

Fall will also mark a new chapter for the exhibition. The show will travel to the art gallery at Eastern Connecticut State University in Willimantic in September. In the meantime, Fabijanska will keep the discussion alive through programming. After a screening of Ukrainian filmmaker Alexander Dovzhenko’s silent film Zemlya (1930) with music by Kyiv-based quartet DakhaBrakha, on July 27 the gallery will host a virtual panel with two of shows artists and curator Ksenia Nouril.

“The show gives ‘first names’ to the war,” Fabijanska says. “The show proves art is a tool for survival and to process our fears.”

- Women at War, until 26 August at Fridman Gallery, 169 Bowery, New York