Bruce Horak is a Canadian artist, musician, performer—and Star Trek’s first legally blind main cast actor. He portrays Lieutenant Hemmer, a blind, albino, telepathic alien who is the Enterprise’s chief engineer on the new streaming series Star Trek: Strange New Worlds. Horak, who lost more than 90% of his vision when he was an infant due to cancer, shares more than a visual impairment with his character on the show. He is similarly philosophical, forthright, dryly funny and determined.

A little over a decade ago, he started painting portraits of friends and fellow actors, with the aim of creating 1,000 portraits (he’s more than halfway done, with 640 so far). This practice turned into a second career, and in between acting projects, he continues to paint, conducting portrait sessions over Zoom as well as in-person since the pandemic started.

In 2013, he created the one-man show Assassinating Thomson, in which he paints a group portrait of the audience while telling them the mysterious history of the Canadian painter Tom Thomson, who was found dead in 1917 after disappearing during a canoe trip. He has taken the show across the country and is performing it this month at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa (26-31 July).The Art Newspaper spoke with Horak about his art practice over Zoom, while he was in Toronto working on another play.

The Art Newspaper: You started off your career in theater, but it sounds like all of the arts have been a big part of your life.

Bruce Horak: I grew up in a really artistic household. I started drawing and painting when I was really little—we always had music in the house, so I was playing piano, and then took up the drums and guitar when I was in junior high. Eventually, I focused on drama and thought I would go into playwriting. But I got bit by the acting bug. My career has been writing, performing, directing, producing, composing, singing and dancing. I jokingly say—although some people take me seriously—that I’d do absolutely anything to keep from doing a real job.

Did you have any training in visual art? You have a lot of technical skill.

I took art classes through junior high and high school. When I got to grade 11, there was a choice of whether I was going to take either theater or art classes, or if I could do both. And my high school art teacher—she was a fantastic teacher, but she was brutally honest—said, “I don't know the school that’s going to know how to handle how to teach a blind person how to paint or draw. There isn’t an institution out there that’s going to do that for you. Because in theater, it’s all about pretending to be something you're not. And if you can get on stage and convince me that you're sighted, then maybe that's the course for you.” I certainly sat down and thought pretty hard about what my post-secondary career was going to be. And theater school was accessible, it was affordable.

I went to an integrated school, I didn't go to the school for the blind or visually impaired, and as any teenager will tell you, there's this compulsion to want to fit in as much as possible. I struggled to create work that looked like a sighted person created it. I wanted to be able to show my work and people would say, “Wow, this is really great.” And then on top of it, “Oh my God, he can't see? Well, that's even better.” But it was pretty apparent that there was something up.

Years later I had an audition for a movie called Blindness, and in it, everybody goes blind. And my agent said, “Hey, you'd be perfect for this. The only problem is you don't look blind.” So I went to the Canadian National Institute for the Blind and got my very first white cane when I was 33 years old. It just completely changed my life. I started using it and realised that I probably should have been using it my whole life, but of course there's the fear, and there's the want to fit in and appear sighted, and all that other beautiful garbage that goes along with having a disability.

As I started to use the cane, more people started to ask questions about my eyesight. So I started to paint portraits of people as I see them, and actually exploring how it is that I see it instead of trying to create a work that looks like a sighted person created it. And that developed into a career in painting, which I honestly never expected.

There's a disability arts movement in Canada that kind of ebbs and flows. Every 10 years or so it seems to come to the forefront, […] then they get a couple of festivals—and then they cut the funding—and then it comes back. I just happened to catch it at a high-water mark, if you will. I started meeting other artists with disabilities, visual impairments, and had a few shows. It just seems like the door is open right now.

Installation view of Bruce Horak's portrait Installation at Tangled Gallery, Toronto. Michelle Peek Photography. Courtesy of Bodies in Translation/ Activist Art, Technology & Access to Life, Re•Vision/ The Centre for Art & Social Justice at the University of Guelph.

Do you think perceptions have changed in general about artists with disabilities?

It comes and goes. My theater history teacher back in school talked about the pendulum of art, and how it was always swinging back and forth, so you go from one extreme to the other. He was talking primarily about realism versus surrealism in theater, but I think that in terms of the spotlight on particular voices being heard, it's constantly swinging back and forth.

I've witnessed it in my admittedly brief career as an artist in Canada. There was, at one point, a whole disability arts festival in Calgary. And then again, the government shifted, it went from a liberal to conservative, so arts funding gets cut. And then the movement sort of goes underground—and that's when stuff starts to flourish.

I've certainly witnessed it in the last few years of casting calls in film and television looking specifically for blind or vision-impaired actors to play roles. That's how I stepped into Star Trek—they were specifically looking for a blind or visually impaired actor to play a blind alien. That sort of casting call wasn't around five years ago.

Bruce Horak as Hemmer and Celia Rose Gooding as Uhura of the Paramount+ original series Star Trek: Strange New Worlds. Photo: Marni Grossman/Paramount+

But making sure you keep working seems to be a big impetus for you. You’ve said before that an artist’s job is just to keep painting.

That's it 100%. And there's nothing more frustrating than an artist who's calling himself an artist and then hasn't picked up a paint brush in 10 years. Or a musician who's got their piano covered with a blanket and plants on top of it. That's not a piano anymore, that's a table. You have to kind of take a step back and go, are you creating?

How did you first turn to painting?

I rented a place in Calgary, Alberta. It was this beautiful old church that some theater friends of mine had converted into a performance space and workshop. I was going to run a clown class, and on the first day, I had just one student show up. This was supposed to be a 10-day, pretty intensive workshop, and it was just going to be me and my buddy, Brandon.

We'd gone to theater school together, and he knew that I had a visual impairment, but he didn't know the extent of it. And I said, “Well, I'm not going to run this workshop for you, but I'll make you a coffee, let's sit and have a chat.” And we started talking about my eyesight, and my cane and he asked all sorts of questions. So I sat and painted his portrait to show him how I see him.

And while we were chatting, he gets a text message from his wife, who is a painter as well, asking him to stop at the art store. There was a call for submissions at the Harbourfront Center in Toronto, looking for portraiture. It was just absolute serendipity. They were looking for 12 images and an artist statement.

So that night I went downtown to a theater bar in Calgary, and I just started asking all the actors who were there, “Hey, I've got the studio for a week, would you come and sit for a portrait?” And I found myself totally booked. I was doing three portraits a day. I just packed it in, 25 portraits done in the 10 days I had the space and I felt like I had a submission.

The next thing I knew I had a showing of one of my pieces at the Harbourfront in Toronto. And eventually doing this portraiture turned into my performance Assassinating Thomson, where I paint a portrait of the whole audience, and tell my story, and answer questions. And it essentially is a portrait sitting, but instead of a one-on-one, it's one-on-200.

The dream with that show is taking it beyond Canada. It's not just a story for Canadians, it's a story of Canadian art. I’d like to be made a cultural ambassador to the world, and tour Assassinating Thomson to all the embassies, and someone should make that happen. Justin Trudeau needs to give me a—what do you call it?—a Governor General's award and make me an ambassador. And if this could happen before I'm 50, that would be great.

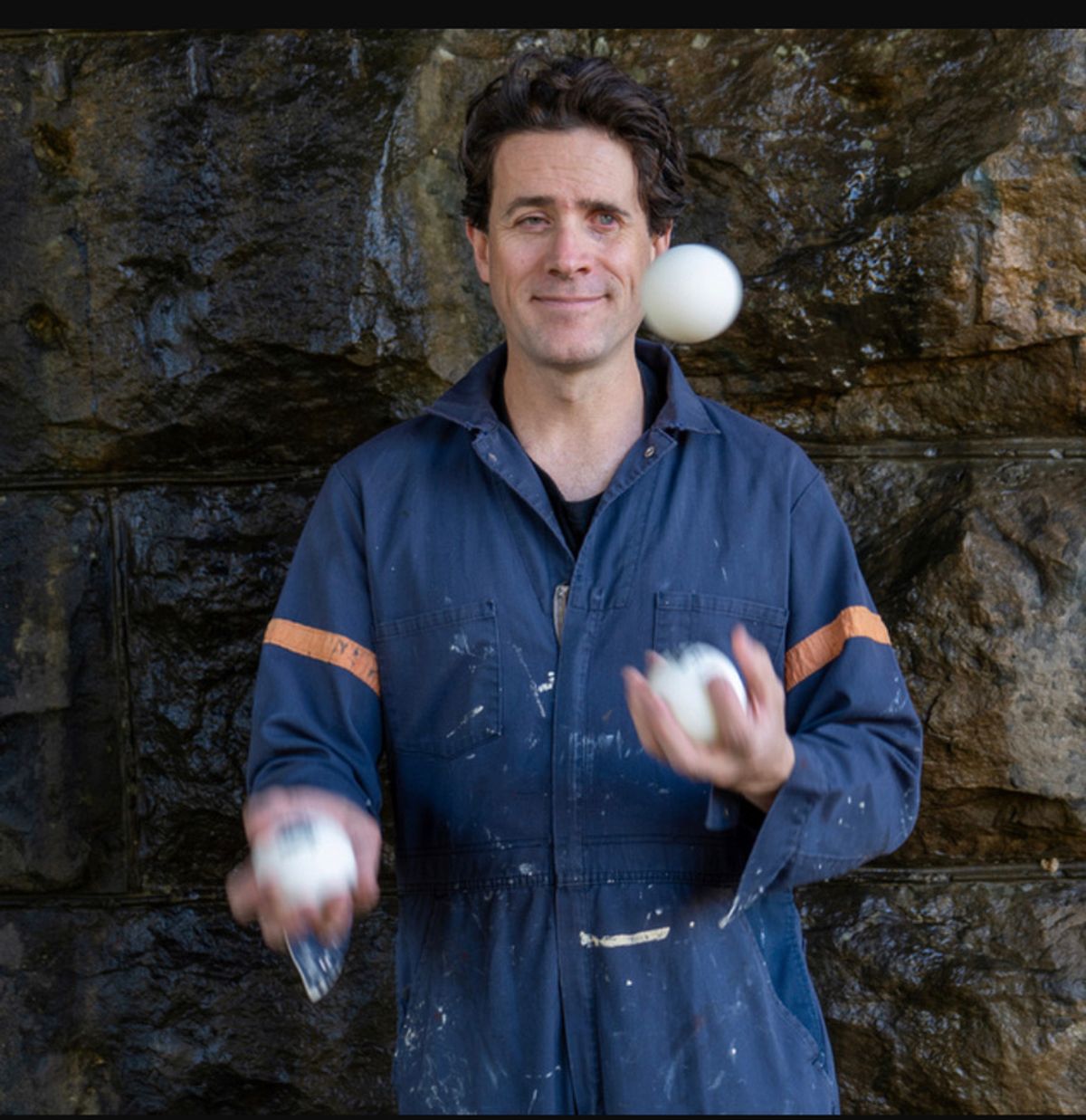

Bruce Horak in a publicity photo for Assassinating Thomson

What's the process like painting a group portrait versus painting individual portraits?

I really had to let go of my desire to get it right, because it's only an hour that I give myself. So it's not going to necessarily be representative, there’s an abstraction to it. And I'm talking at the same time, which I think a lot of artists will tell you, is like using conflicting parts of your brain. I'm trying to operate on all these different cylinders at once, it's a real exercise in full brain usage.

I've done this show now maybe 300 times in 10 years, and I look back on those early ones, when I was really trying to get figures down, and get the lighting right. Now it's more of—here's the impression. Because I have really narrow tunnel vision, so in order for me to see a whole, I have to focus on small parts at a time. Whereas in reality, I do a quick scans all the time. I'm taking in as much as I can to see if there is something that's going to hit me in the head or coming at me quickly. Once I've figured out that there's no immediate danger, then I can relax and just take things in. So it's a fun balance between just pure impressionism and—there's a yellow coat, there's a white hat, there's a pair of blue boots. There's a play between different approaches within a single painting.

It also depends on the venue, it depends on the day. Sometimes, my eyes are really tired and I don't make out much more than glaring lights. It depends on the people that are sitting there and what they're wearing. And that's true of my individual portraits as well.

Sitting back and just trying to see how I see is really liberating. And it's a real challenge, because as somebody who has a visual impairment, I spend most of my time out in the world trying to figure out how other people are seeing. This is just an opportunity to sit back and go, “Okay, so how is my brain interpreting this?” I think it's in that Betty Edwards book, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, where she talks about how the eye is the instrument and the brain is actually the conductor, it is the true artist.

Your brain interprets what your eyes see. And my eyes are so heavily damaged that I think my brain is filling in a lot of what my eye isn't seeing. I'm constantly editing out the floaters, the flashing lights and the auras, because that's not necessarily what’s out there. It's what’s in my eye. So it's taking a step back and actually witnessing the reality that I'm seeing, and trying to interpret and express it. Which I guess is the goal of every artist, to express what they see, how they see.

Installation view of Bruce Horak's portrait Installation at Tangled Gallery, Toronto. Michelle Peek Photography. Courtesy of Bodies in Translation/ Activist Art, Technology & Access to Life, Re•Vision/ The Centre for Art & Social Justice at the University of Guelph.

You’ve been touring this show around the country, and you’ve been painting and drawing all over the place. You call yourself a Hobo Sapien, which I think is a great name for this romantic idea of an itinerant artist. Is that how you see yourself?

That was my dream, when I started busking in high school, a buddy of mine and I would go downtown and sing for change. And I found it totally romantic, the notion of, like Woody Guthrie—just grab your guitar and hop on a train town to town. There’s a real desire—this certainly ties into my disability—for autonomy and to make my own way in the world with my skills.

And yet at the same time, I was always working with other people because there was a fear of doing it on my own. Going and busking by myself is terrifying, because I wouldn't be able to see if somebody was rushing in to take the money out of my guitar case, or was coming at me. So I would always work with my friends. And slowly over time I've learned to find that autonomy. The white cane has actually been probably the best tool that I’ve ever had, because it's allowed me to travel independently on my own, to do the work that I want to do. I wish I had had it much earlier.

I don't know that I would've gotten to where I am, had I had it earlier though. I probably would be on a different path. But it really is an incredible tool. And I know a lot of visually impaired people who have fought against it. And people who are losing their eyesight who see the stigma around having the white cane, and the fear around it. Is this is going to make me a target, or this is going to weaken me in some way, or is this going to make me stand out? But for myself—and I say this to anybody who's considering it—it's a great tool. And every tool is a weapon if you hold it right, to quote Ani DiFranco.