For decades, a handheld mirror in the Cincinnati Art Museum’s collection of East Asian art was thought to be a simple looking glass made of bronze, with an invocation of the Amitābha Buddha inscribed on one side. Now, after a chance discovery by a curator, the circular object has become something of a mystery: when illuminated with a bright light, it projects a gauzy image of a Buddha surrounded by rays of light—a figure who is otherwise undetectable.

“There is nothing on the surface, it’s just a polished reflecting surface with a bit of corrosion,” says Dr. Hou-Mei Sung, the museum’s curator of East Asian art, who found the hidden image. “It doesn’t give you any clue.”

Thought to date to the 16th century, the mirror is an example of a “magic mirror”, or mirrors known as 透光鏡 (tòu guāng jìng), or light-penetrating, that were made in China and Japan. It will be on permanent view from 23 July in the East Asian galleries.

Front and back of the Buddhist bronze mirror, China or Japan (15–16th century). Courtesy Cincinnati Art Museum. Photo: Rob Deslongchamps.

Sung, who had last displayed the work in 2017 in an exhibition on Japanese arms and armour, revisited the mirror because she was on the hunt for more Buddhist objects to include in a rehang of the galleries. During her research she learned about Buddhist magic mirrors, which typically featured the same inscription: “Hail to Amitābha Buddha”—the Buddha of Infinite Light—on the back.

“Just by chance I asked our object conservator to do a test, to shine a light on the back to see if it has this magic nature,” Sung says. “To our surprise, we found that it does indeed project a hidden image of the Buddha.”

The mirror was accessioned in 1961 but entered the collection earlier. With no complete record to reference, Sung has been piecing together its history and significance by looking at other examples of magic mirrors. In part because of their cryptic nature, however, few others have been identified. One is in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum and another in that of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Both date to the Edo period and feature the same six-character chant to Amitābha in simplified Chinese characters, which were commonly used in Japan. The Cincinnati Art Museum’s mirror, however, uses traditional characters, suggesting that it was made in China.

The origins of magic mirrors can be traced to the second century BCE, during the Han Dynasty, Sung says, when people held small mirrors in front of sunlight to cast decorations on their backs onto a wall. These early designs were traditional, consisting of repetitive circular patterns and auspicious sayings, and they were used for ritual purposes. The curator believes the Buddhist versions developed during the Ming Dynasty and were likely used for worship of Amitābha, with adherents chanting the invocation to gain rebirth into the Western Paradise after death. They were more technologically complex, showing no trace of their projected designs.

“It appears to be more magic,” she says. “It’s not reflecting the decoration on the back of the mirror, but an image hidden inside the mirror, like a miracle.”

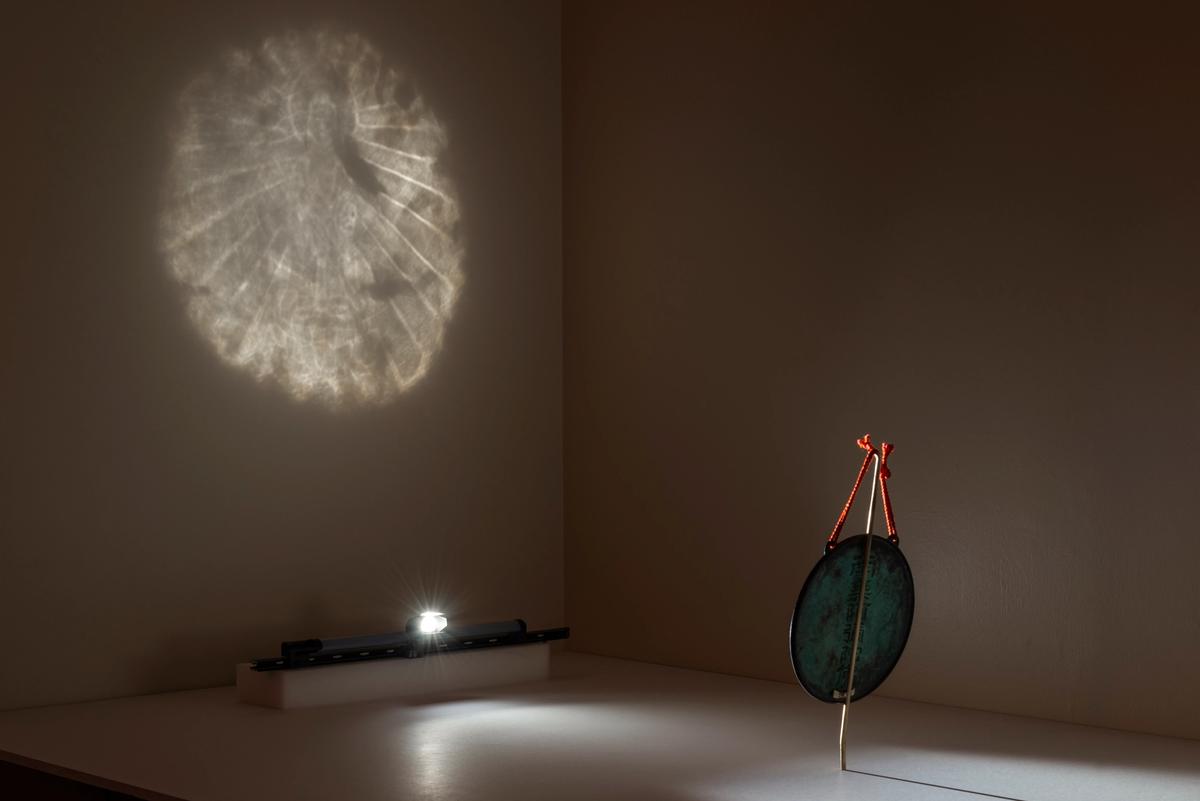

Buddhist Bronze Mirror, China or Japan (15–16th century). Courtesy Cincinnati Art Museum. Photo: Rob Deslongchamps.

Scholars have been researching the craft behind magic mirrors as early as the seventh century. One theory is that makers polished the backs of mirrors in a deliberate way to create subtle but precise marks to manipulate light that hit the surface. Modern research has found that the technique involves “two metal discs soldered together so the Buddha image is sealed within the mirror on the back side of the front surface,” Sung says. “It is very technical. It is tremendously difficult to reproduce.”

The Cincinnati Art Museum will illuminate the hidden Buddha when the mirror goes on display by shining a light on its reflective surface. Visitors will still be able to see the other side and read the inscription as they gaze upon the phantasmagorical figure. “We are just trying to create a way to demonstrate the magic nature,” Sung says.