For more than 90 years, architects have been at the heart of the Triennale Milano art and design expos: from the hypermodern Casa Elettrica at the 1930 international exhibition by Gruppo 7 to the display installations at this year’s edition designed by Francis Kéré—winner of the 2022 Pritzker Architecture Prize—who will also curate two installations dedicated to the voices of the African continent.

So when Triennale Milano and its Museo del Design Italiano, home to the Triennale's permanent collection, chose to explore its 99-year history in virtual reality (VR), it was more than appropriate that the museum curators, working with the Milan-based creative agency Reframe VR and the VR platform Vive Arts, should have chosen the architecture of the Palazzo dell’Arte, the international exhibition’s purpose-built 1933 headquarters in central Milan, and the drawings by its architect Giovanni Muzio, as the narrative and aesthetic framework for the VR piece. Impluvium, the first chapter of the VR experience 1923: Past Futures, will be launched at the inauguration of the 2022 international exhibition—Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries—on 15 July, with the remaining chapters due to be launched on 1 September.

Recreating lost spaces

The project focuses on two areas of virtual reality of specific use both to Triennale Milano and to museums more widely: the ability to recreate lost objects or installations—as Matteo Lonardi of Reframe VR says, “to recreate lost spaces in three dimensions so that the viewer can live in them”—and the ability to play with narrative timelines. Whether in the biography of an artist or an institution, VR has the power to offer users a cleaner and clearer documentary line. It can offer a choice to follow “life” or “works”—and to switch between the two—rather than a single “life-and-works” narrative, with other narrative spaces potentially devoted to historical, political or cultural context. It is an approach well-suited to managing the information surfeit available in a retrospective of either an artist or an institution.

Vive Arts—which has previously worked with Tate, in London, on a Modigliani studio recreation in VR, and with the Victoria and Albert Museum on an Alice in Wonderland experience launched in 2021—approached Triennale Milano to suggest a VR piece. “Initial ideas focused on looking at spotlighting an Italian designer represented in the collection,” Celina Yeh, executive director of Vive Arts, says, “but [ultimately] the Triennale team decided to use VR to showcase moments from the history of the international exhibition.”

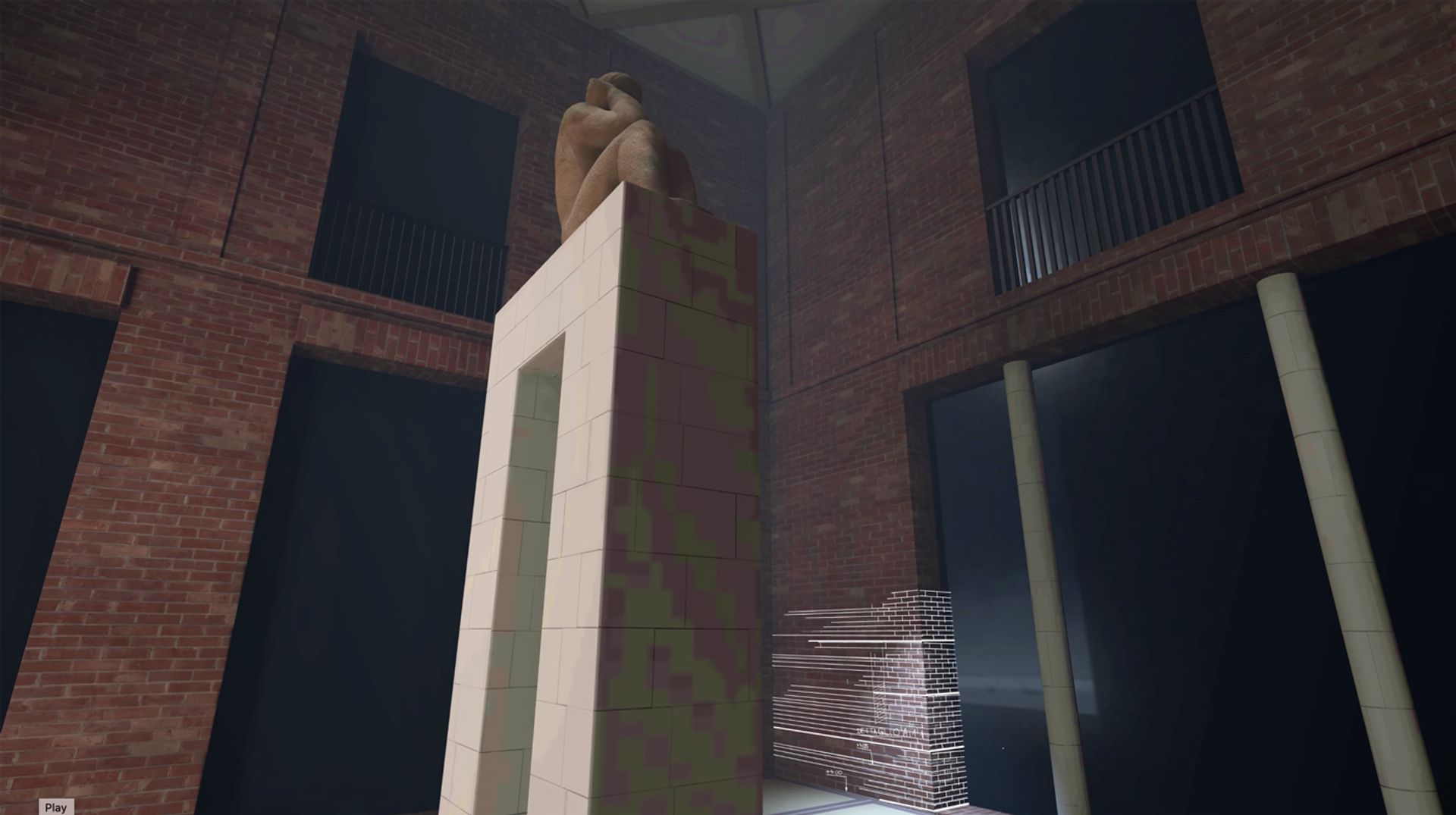

The Impluvium in Giovanni Muzio’s new-built Palazzo dell’Arte in 1933, with fountain statuary by Leone Lodi, designed by Mario Sironi. It is being recreated as the opening chapter of the triennial experience Triennale Milano—Foto Crimella

The Sironi sculpture features in a preview still from Impluvium, the first chapter of the VR experience 1923: Past Futures, produced by the Triennale di Milano with Reframe VR and Vive Arts, and inspired by the aesthetic of 1933 drawings by the architect Giovanni Muzio

Vive introduced the Triennale Milano team to Reframe VR—founded by the Milanese brothers Matteo and Francesco Lonardi—whose Reframe Saudi attracted large crowds at Art Dubai in 2018. The brothers had worked with Vive previously on Il Dubbio, a two-episode VR piece, which was shown at the 2021 Venice Film Festival. Matteo Lonardi says that museums are ideal partners for VR makers: “Because the problem of VR is distribution, the museum already has the built-in audience—both the space and the audience.” The Triennale Milano curators are targeting two groups with what is their first VR piece. In a statement to The Art Newspaper, they said they are looking to attract local audiences aged 20 to 35—“they are already part of our public but we would like to increase their presence and involvement with the institution”—as well as “cultural and tech-enabled experience seekers and international visitors”.

Exploring past futures

The experience will recreate stand-out installations from the fractured history of Triennale Milano's international exhibition: the event was launched as a biennial in Monza, 20km north of the centre of Milan, in 1923, before becoming a triennial in 1930 and transferring to Milan in 1933. There was an unavoidable break during the Second World War, and a 20-year gap without an official expo between 1996 and 2016. The Triennale set up its Museo del Design Italiano in 2009 and has established an outstanding archive, a rich visual resource for the VR project.

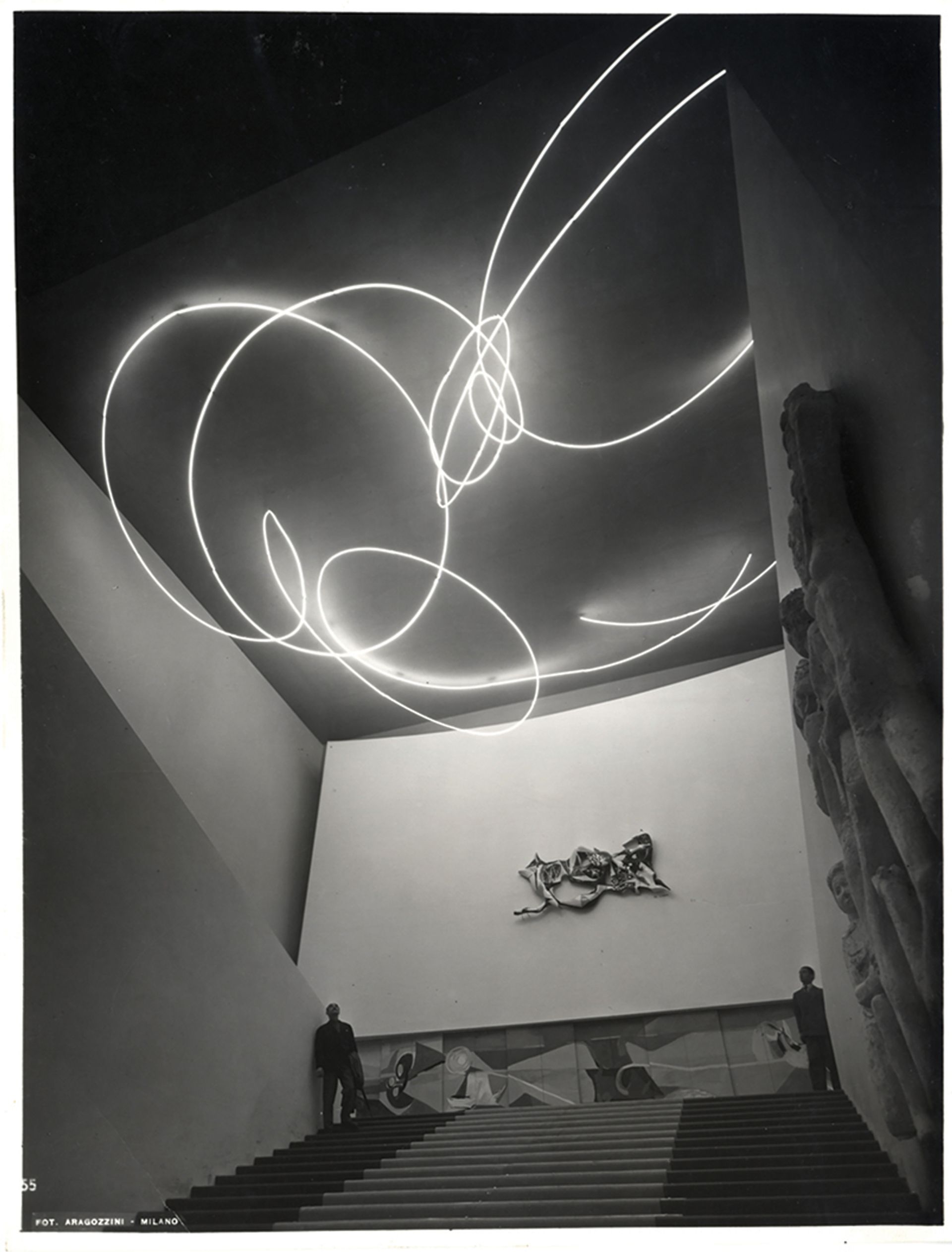

Lucio Fontana’s neon light installation Luce spaziale on the main staircase, a star exhibit at Triennale Milano's first great post-war international exhibition, in 1951, floating above a ceramic piece by Neto Campi and a mural by Giuseppe Ajmone Triennale Milano—Foto Aragozzini

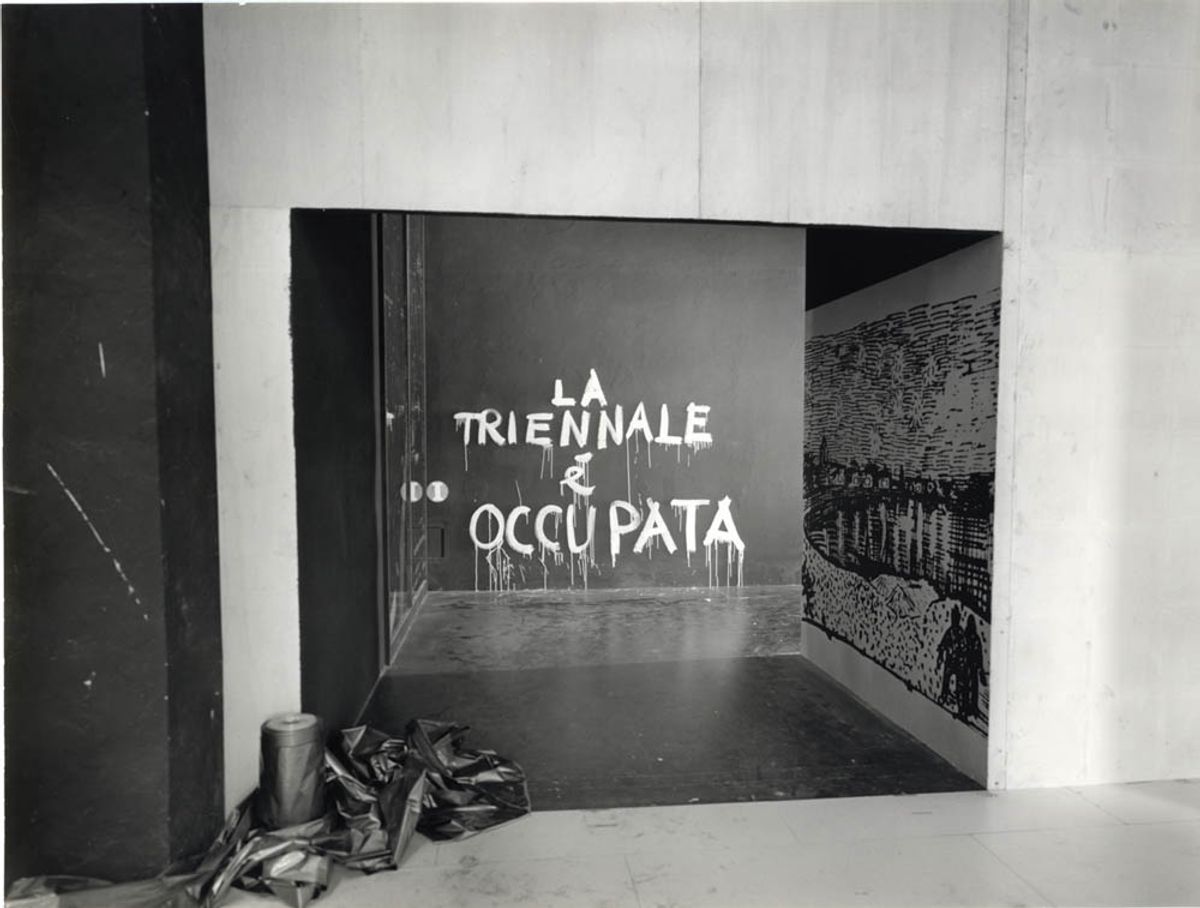

The historic installations that will be brought to life include the Impluvium courtyard installed in the newly built palazzo in 1933, with statuary designed by Mario Sironi; the fantastical neon installation on the main staircase by Lucio Fontana from 1951; the futuristic Caleidoscopo from 1964; the “Triennale Occupata” of 1968, when protestors, fired by the demonstrator-led evenements in Paris, occupied the Palazzo dell’Arte; a recreation of the Room of Change, the first part of the 2019 Broken Nature international exhibition; and a virtual visit to the museum’s archive, which will serve as a gateway to a piece by the landscape artist Giuliano Mauro, before coming home to what Lonardi calls “the wise voices” of the 2022 expo.

Lonardi, who is working closely on the VR experience with Marco Martello, Triennale Milano’s digital manager, explains how Muzio’s drawings suggested the framing for the VR experience. “It was important to ground the experience in some kind of identity. And the identity of the Triennale is related to architecture and the drawings of Giovanni Muzio,” he says. “So we are trying to create a look which is a bit vintage. You click [using the hand controllers of a Vive headset] and see the lines of the Impluvium forming around you.”

Lonardi and the curators see the experience as a “time machine”, where the user will be able to move between the installations from 1933 to 2022 and back, and as grounded in the “past future”. (As part of the 2022 international exhibition, Marco Sammicheli, the director of the Museo del Design Italiano, is curating a show whose subject, La tradizione del nuovo—“The tradition of the new”—plays with this “past-future” theme.)

For the Triennale’s curatorial team, the VR piece “is a starting point. Its modular structure allows it to be enriched and expanded,” the statement says. “Next year we will celebrate Triennale Milano’s hundredth anniversary, and with virtual reality we will be able to explore more past futures. To be continued.”