This year is shaping up as the year corporate Australia distances itself from art in a big way, with the Construction and Building Unions Superannuation fund (CBUS) poised to sell off its Australian art collection at Deutscher and Hackett’s Melbourne auction house across July and August.

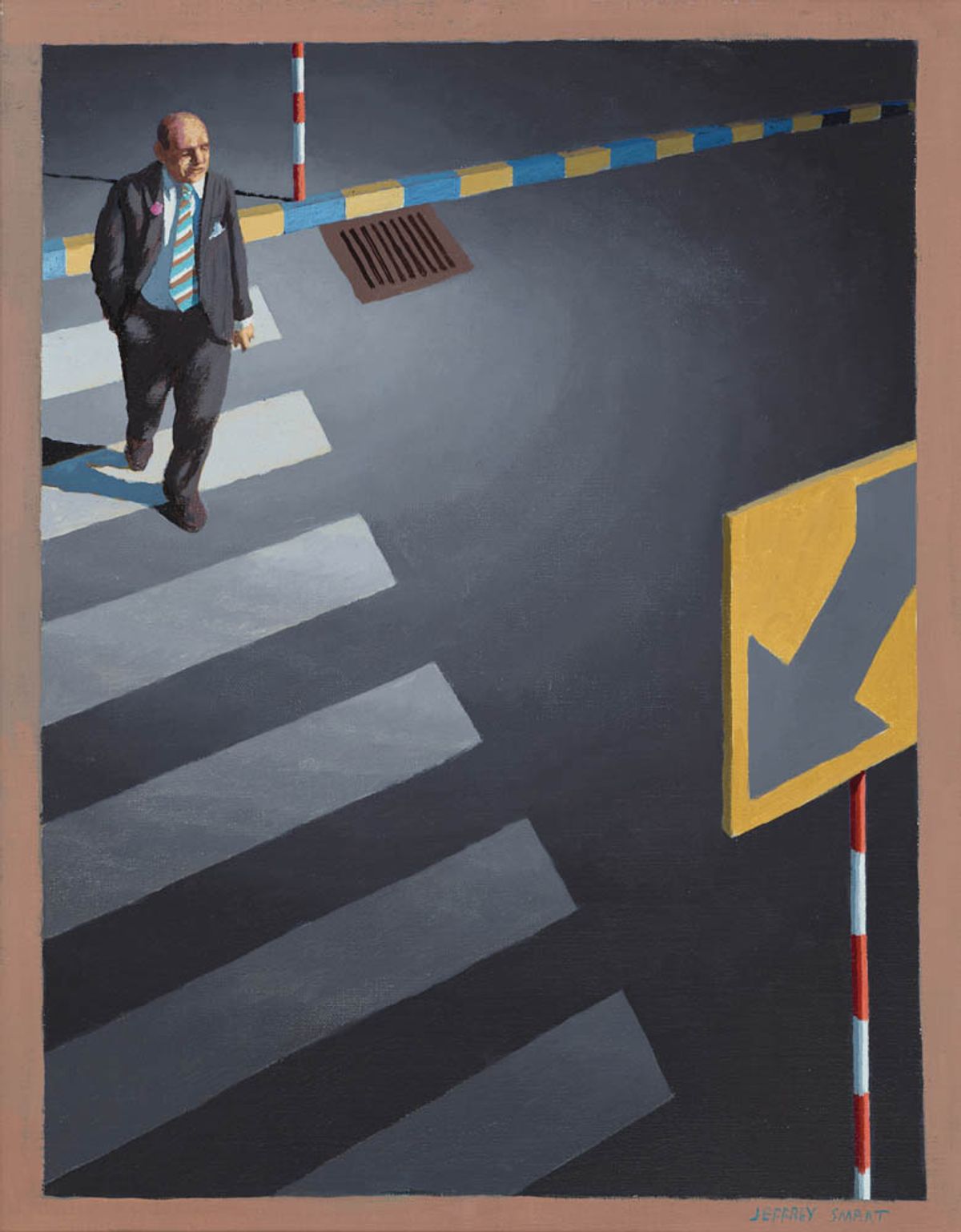

The auction comes hot on the heels of National Australia Bank’s fire sale of 2,500 works for A$10m (US$7m) in February. With CBUS expected to receive A$9m (US$6.3m) from around 300 works, it’s an indication of the quality and depth of a collection that includes paintings by Margaret Preston, Fred Williams, Sidney Nolan and Jeffrey Smart.

While the auction will give collectors access to works that are hard to come by from some of the country’s most bankable artists, the biggest losers will undoubtedly be the Australian regional galleries who have benefited from the long-term loans coming out of the collection’s stockroom.

Since its inception, the CBUS Collection of Australian Art has provided those galleries with access to art of the calibre only found in state and national collections through an arrangement brokered by its founder, the late Joseph Brown.

Margaret Preston's Coastal Gums (1929), est. A$180,000-A$240,000

“He insisted that [the Collection] wasn’t locked away,” Brown’s nephew Norman Rosenblatt, also an art collector, tells The Art Newspaper. “These [regional] galleries haven’t got the money to buy the paintings,” he says.

Geelong Gallery, Bendigo Art Gallery and Benalla Art Gallery have bolstered their permanent collections with long-term loans of between ten and 20 works each. While others have borrowed works on an ad hoc basis to support curated exhibitions.

For 15 years the collection has been managed by Latrobe Regional Gallery (LRG) in Morwell, nearly two hours east of Melbourne. According to its director Bec Cole, CBUS appointed LRG because the gallery shared a “connection” to the industries the fund services, namely coal-powered energy production and other heavy industries in the region. Pre-pandemic there was “a lot of [CBUS] member engagement with the collection”, Cole says.

In 2020, LRG staged Friendly Country, Friendly People, an online exhibition of Western Desert artists first seen in Alice Springs in 1990 and purchased in its entirety by Brown shortly afterward. It’s “sad that the works will be separated now”, Cole says.

Despite a number of the works in the collection being of “interest” to LRG, Cole believes it’s unlikely the gallery will bid, “given the price range”.

Just because you buy an asset doesn’t mean you can’t be benevolent and give some of the asset away.

Rosenblatt feels that even though Brown knew CBUS viewed the collection as an investment, he would be “turning in his grave” if he knew it was going to be “flogged on the open market. Just because you buy an asset doesn’t mean you can’t be benevolent [...] and give some of the asset away.”

Fred Williams's Sapling Forest (around 1960-62), est. A$180,000-240,000

In the late 1980s, Brown and Australian art historian Bernard Smith approached the superannuation fund (Australia's term for a retirement pension fund) with a proposal to invest in art. They argued Australian art was undervalued and at risk of being scooped up by international buyers. Shortly afterward the fund appointed Brown as art consultant and committed A$2m (US$1.4m) to establish a wide-ranging collection of Australian colonial, contemporary and Indigenous art. The final acquisition was in 2007, a portrait of Brown by Fu Hong.

Although it’s unclear why CBUS has decided to sell, some have speculated it is in response to superannuation disclosure legislation introduced by the government in November 2021. Under the changes, designed to improve the transparency of investment holdings, around 500 Australian superannuation funds were forced to disclose the value and weighting of their investments to members.

Data published by CBUS and viewed by The Art Newspaper suggests the process exposed their art collection to a heightened level of scrutiny, with individual works appraised and sorted in one of four distinct “asset classes” based on their rate of return.

Certain high-value artworks, with a combined market value of around A$7m, were classed as "high growth" assets. But the bulk of their collection made up around 8% of the fund’s “conservative growth” asset class with a very low rate of return.

When CBUS made its first stake in Australian art, it represented 0.5% of its investment portfolio. More than 30 years later, CBUS’s net worth is a staggering A$54bn (US$38bn), of which its art collection represents a mere 0.02%.

When asked for comment, a spokesperson for CBUS says it “acquires and disposes of assets with a focus on maximising risk-adjusted returns. To get the best outcomes for our members we are now offering the collection for sale.”

But, Rosenblatt says, the art collection is essentially “petty cash”. He adds: “I’m sure the shareholders would be happy if it was donated to galleries.”