Over the last two years, the Morgan Library and Museum staged back-to-back blockbusters showcasing David Hockney’s drawings and everything Hans Holbein. This summer, photographs by Ray Johnson are on tap, along with the drawings of Rick Barton.

Who?

So inquired Rachel Federman, the Morgan’s associate curator of modern and contemporary drawings, when the artist William Anthony offered the museum a gift that included five works on paper by Barton. Acquired 60 years ago from Porpoise Books in San Francisco, they were a marvel to behold.

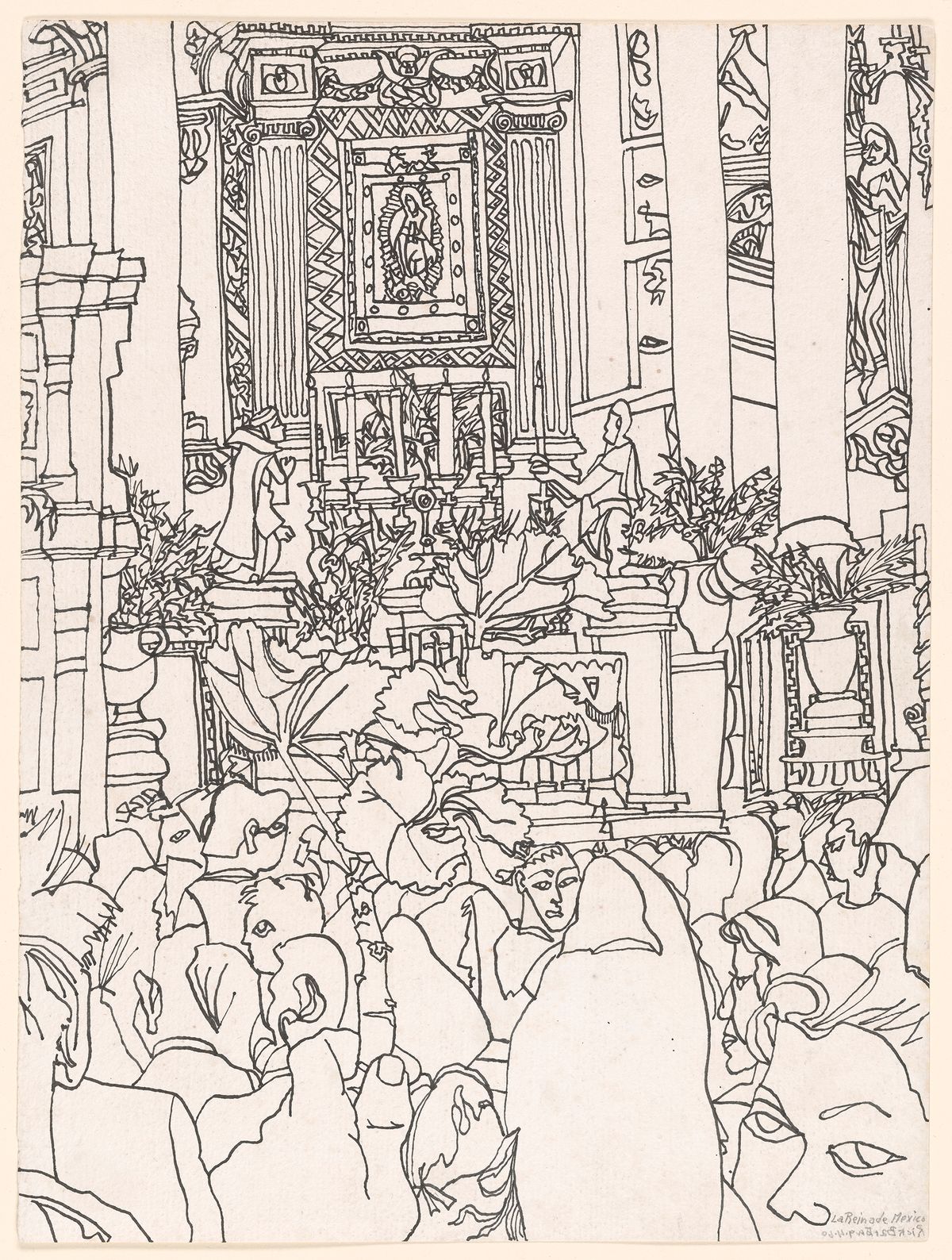

Among them was La Reina de Mexico, a pen and ink drawing from 1960 depicting the shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe, effectively Mexico City’s Mona Lisa. Millions pilgrimage there every year to glimpse the 16th-century apparition, said to have been miraculously imprinted on a peasant’s coat. Though faithful to architectural details of this chaotic scene, Barton inserted his thumb, rendered at the scale of the basilica’s statuary, into the foreground, framing the chaotic scene between it and a hand holding aloft a floral bough.

Her curiosity piqued, Federman began what became a consuming, five-year quest for more material by this mystery artist and any information she could find about his life. The 60 drawings, five linocuts and two astonishing, accordion-folded sketchbooks that now comprise Writing a Chrysanthemum: The Drawings of Rick Barton (until 11 September) are the triumphant fruits of her pursuit.

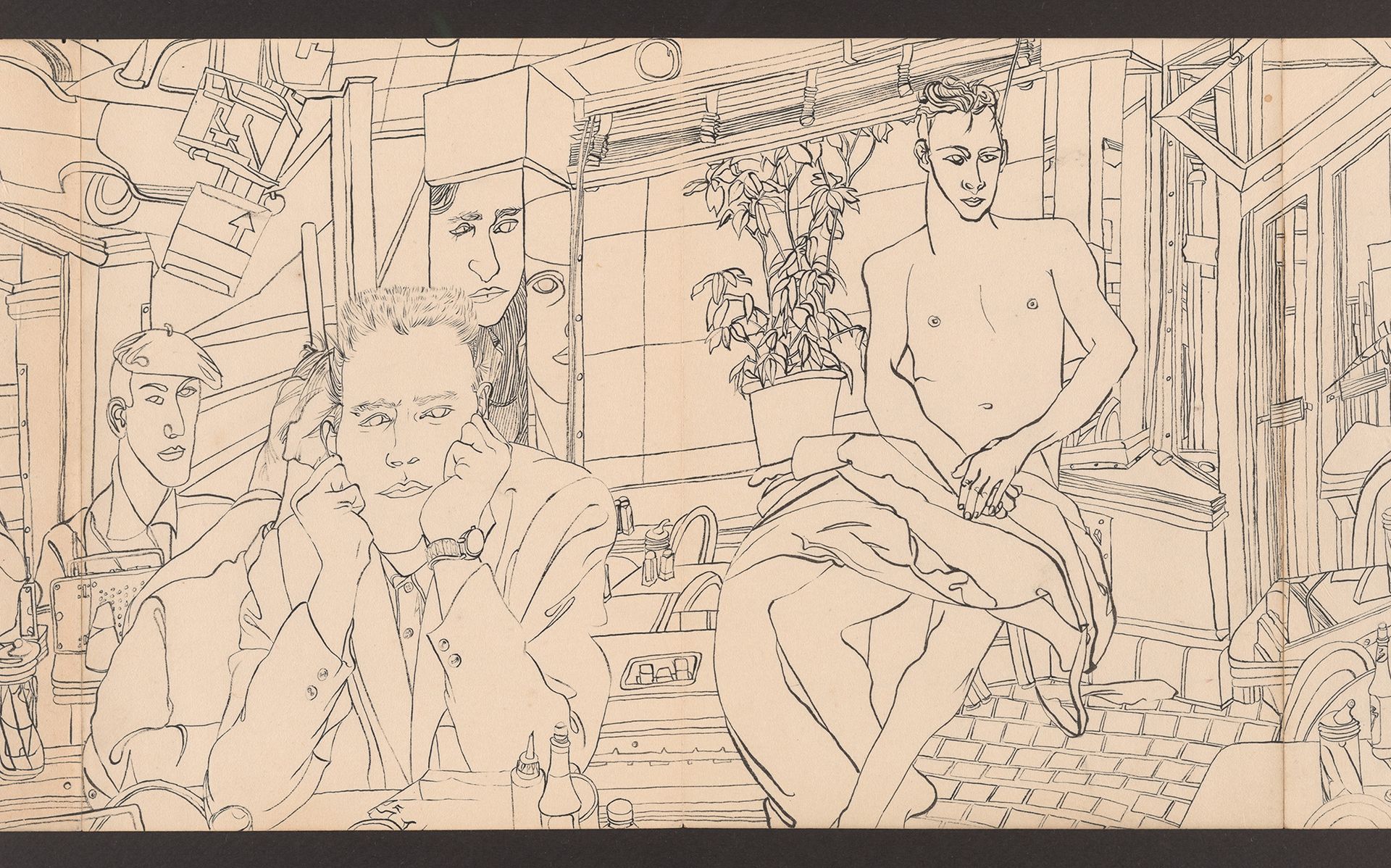

Rick Barton, Untitled sketchbook (detail), 1962. Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries. Photography by Tom O’Connell.

For a 116-year-old institution to move into territory mined more often by galleries and introduce a complete unknown is unusual. Intrigued, I met with Federman to tour the show and was hooked in an instant. The longer I stared at La Reina de Mexico, the more it seemed to levitate from the wall. The subject of another drawing—all works in the show date from 1959-62—is a room seen from behind a man seated with his legs crossed, yet his hands and sketchpad face the viewer, as if they belonged to a ghost. As still pictures go, it’s dizzying—as is the detective story that Federman recounts in her lively catalogue essay.

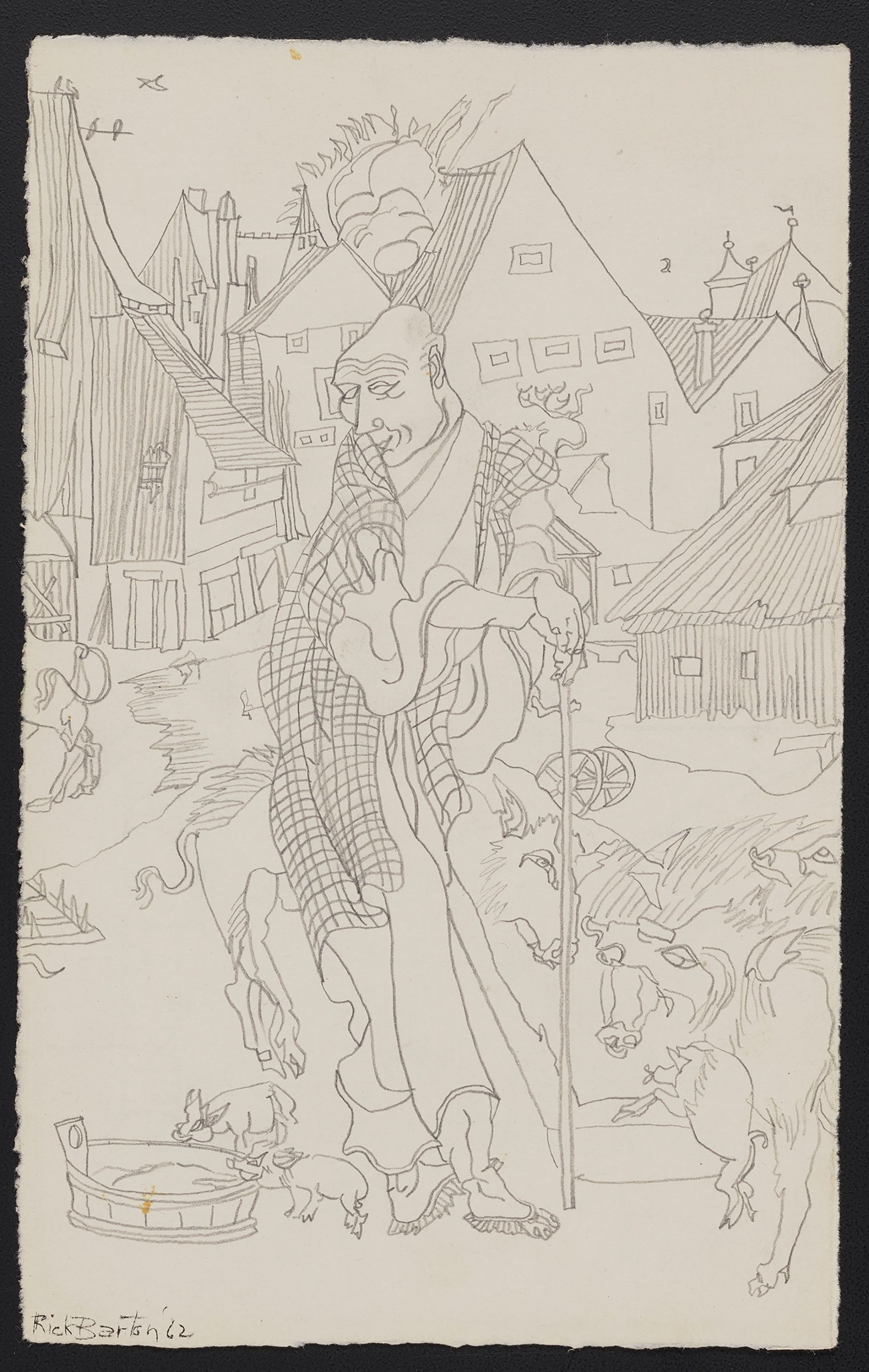

Barton’s biography largely eluded her, but her tale of the hunt is as remarkable as his drawings are obsessive, tender, and strange. I was dumbfounded by their intensity, whether the subject was his shabby room, his intimates or the churches and botanicals he took obvious pleasure in capturing. His fluid way with a line reminded me of early Warhol as well as late Picasso. One work makes simultaneous reference to Hokusai and Dürer. Others seemed influenced by Jean Cocteau, but all of them document Barton’s world in a wholly original way.

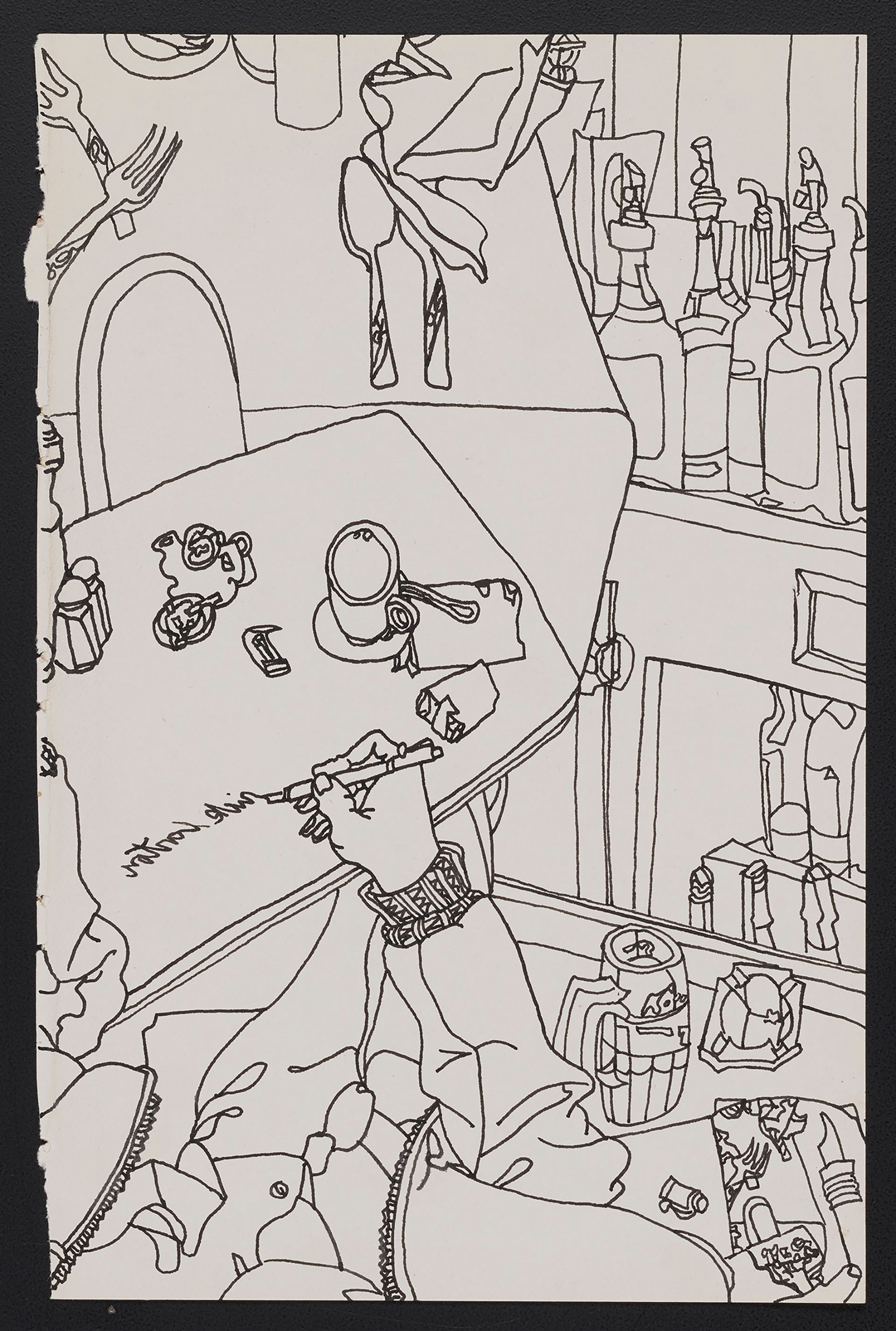

Rick Barton, Untitled [Signature self-portrait], 1961. Rick Barton papers, UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

Barton (1928-1992) grew up impoverished in Manhattan with a single mother and a grandmother. He quit high school and later had some formal training in the school ofAmédée Ozenfant, but largely educated himself by spending long hours in the New York Public Library and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1946, at age 17, he enlisted in the Navy and served in the Far East. Before his early discharge (evidently for mental illness), he picked up an opium habit as well as a Chinese inkpot that he kept at the ready in a vest pocket, with a Japanese drawing tool. In the mid 1950s he moved to San Francisco, where he lived on veterans’ benefits in hotels for transients, sustaining himself on buttered crackers and drawing in cafes patronized by gay men like himself.

He told people he was “paranoid psychotic”, Federman learned from the few whose recognition of his genius made them willing to tolerate his craziness. Foremost among them was Henry Evans, the proprietor of Porpoise Books and founder of the Peregrine Press, which published Barton’s portfolios of linoleum-block prints. In 1971, Evans gave nearly 700 drawings and prints by Barton to the University of California, Los Angeles Special Collections Library, where Federman discovered them in boxes that no one else ever had opened. A couple of sketchbooks turned up at Northwestern University in Chicago. With loans from both institutions and Anthony’s gift, she put together the first-ever exhibition to document Barton’s vision.

Rick Barton, Untitled [After Dürer and Hokusai], 1962. Rick Barton papers, UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

Though solitary, Barton was not a loner. In San Francisco he formed a small cohort that he dubbed “Academia Vinciana”, after Leonardo. “They were the Beats you never heard of,” Federman says. Enthralled by Barton’s skill and the Socratic dialogues he led, members of the group came to cafes for daily lessons in drawing. For two years, one of them, David Nelson, was his lover—and a critically important source for Federman. “Most of the colour in the story came from David,” she says.

Another perspective came from the late, Lebanese-born poet and artist Etel Adnan, who befriended Barton in the early 1960s. In a poignant recollection written for the journal Discourse, Adnan credits Barton for introducing her to the accordion-folded book, a format she then adopted. One of the sketchbooks on view in Writing a Chrysanthemum—the show’s title comes from Adnan’s text—has 28 panels of startling, brushed-ink portraits and lies unfolded in a vitrine that runs to nearly 20ft.

Barton moved to San Diego sometime in the 1970s and died there in 1992. What he did in the intervening years is unknown. He undoubtedly made thousands of drawings in his lifetime, but as far as Federman knows, many have not survived.

“I think people will enjoy the drawings,” she says, “but to me this is about the precarity of art history. There is brilliant art out there that no one is aware of, so this was an opportunity to show one of those artists who fell by the wayside.”

- Writing a Chrysanthemum: The Drawings of Rick Barton, until 11 September, Morgan Library and Museum, New York