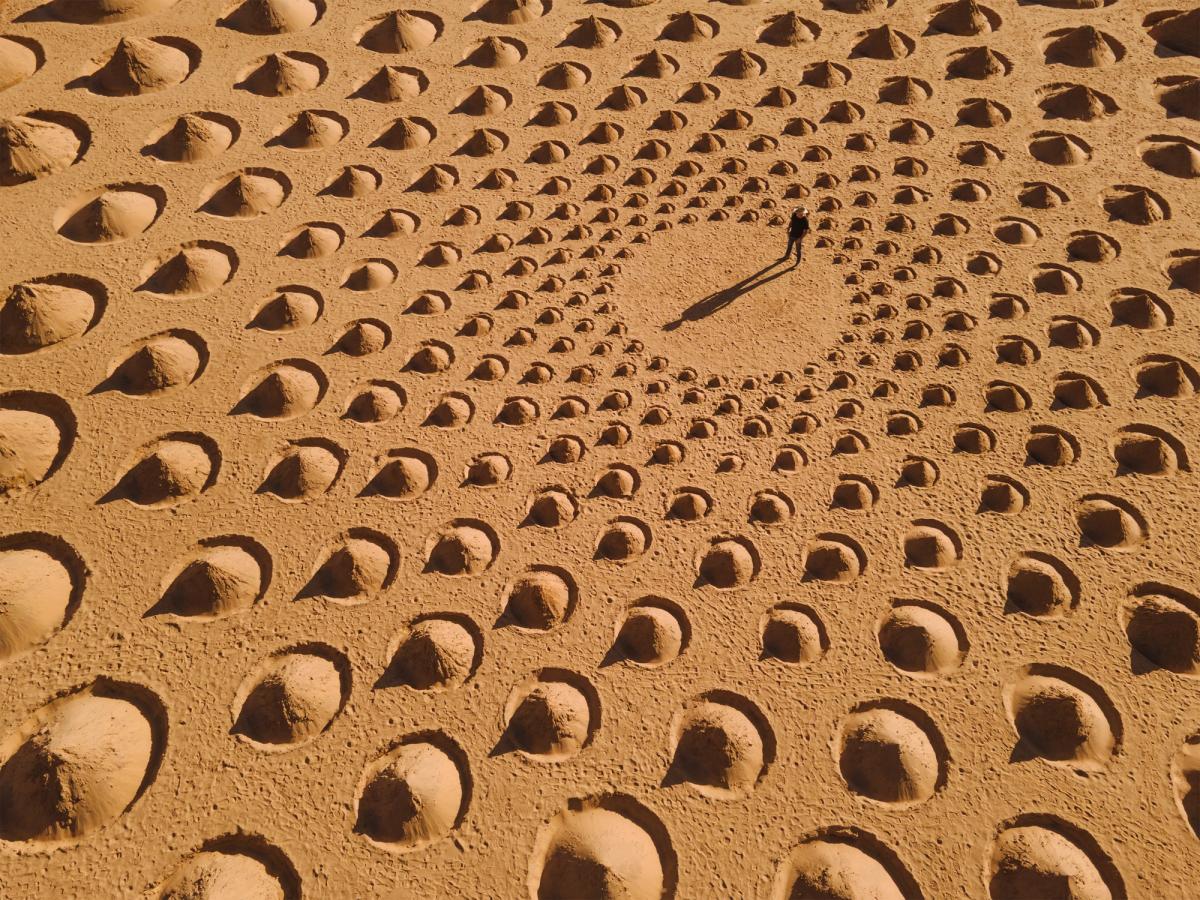

The California-based artist Jim Denevan has created unfathomably symmetrical ephemeral “paintings” on the sand since the mid-1990s, using a stick or rake to draw sometimes miles-long geometric and Fibonacci-inspired compositions. His monumental site-specific work Angle of Repose was a major highlight of Desert X AlUla’s second edition this year, comprising several concentric pyramidal mounds of various sizes that surreally altered the desert landscape.

While Denevan was previously best-known for the cult dining experiences that he has held since the late 1990s, called Outstanding in the Field, in recent years his compelling and laborious artworks have gained overdue recognition. Several photographs and other materials from Denevan’s archive were recently acquired by the Nevada Art Museum’s Center for Art and Environment, a research centre that holds one of the most comprehensive collections of art in natural and built environments that is spearheaded by the scholar William Fox. Denevan “recreates himself and recreates his art [with each work]—it’s not about ego”, Fox says. “It’s about the thing in and of itself.”

Denevan’s work was included in the Faena Festival’s 2019 programming coinciding with Art Basel in Miami Beach, where the artist created a 360-seat circular table symbolic of the cycle of life, death and rebirth. His work has also been exhibited at MoMA PS1, the Parrish Art Museum, the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and the Vancouver Sculpture Biennial.

Denevan’s artistic and culinary trajectory was the subject of the documentary Man in the Field: The Life and Art of Jim Denevan that was released late last year and directed by the California-based director Patrick Trefz. Outstanding in the Field is holding a six-location European tour this summer, which began this week in an Italian sustainable farm in Grosseto and will feature temporary artworks made by both Denevan alone and with collaborators.

Installation by Jim Denevan, Single Line Spiral, Tunitas Creek Beach, CA (2011). Photo: Peter Hinson. Courtesy Jim Denevan.

The Art Newspaper: The documentary begins with you recalling the first “sand drawing” that you made on a beach in California in 1994—the outline of a fish. What compelled you to do that?

Jim Denevan: Most of what I do is on the whimsical side. The fish was an extension of my interest in making whimsical drawings. I covered the entire beach—a pretty substantial area encompassing somewhere between 70 to 100 sq. yards. I was intrigued with the idea of physically exhausting myself and drawing until I filled the beach, or until the tide was coming up. I quickly became obsessed with the process. I was drawing on the sand at every single low tide for many years. It’s been thousands and thousands of miles of walking.

You gradually shifted your focus from figurative drawings to geometric abstraction. What inspired that transition?

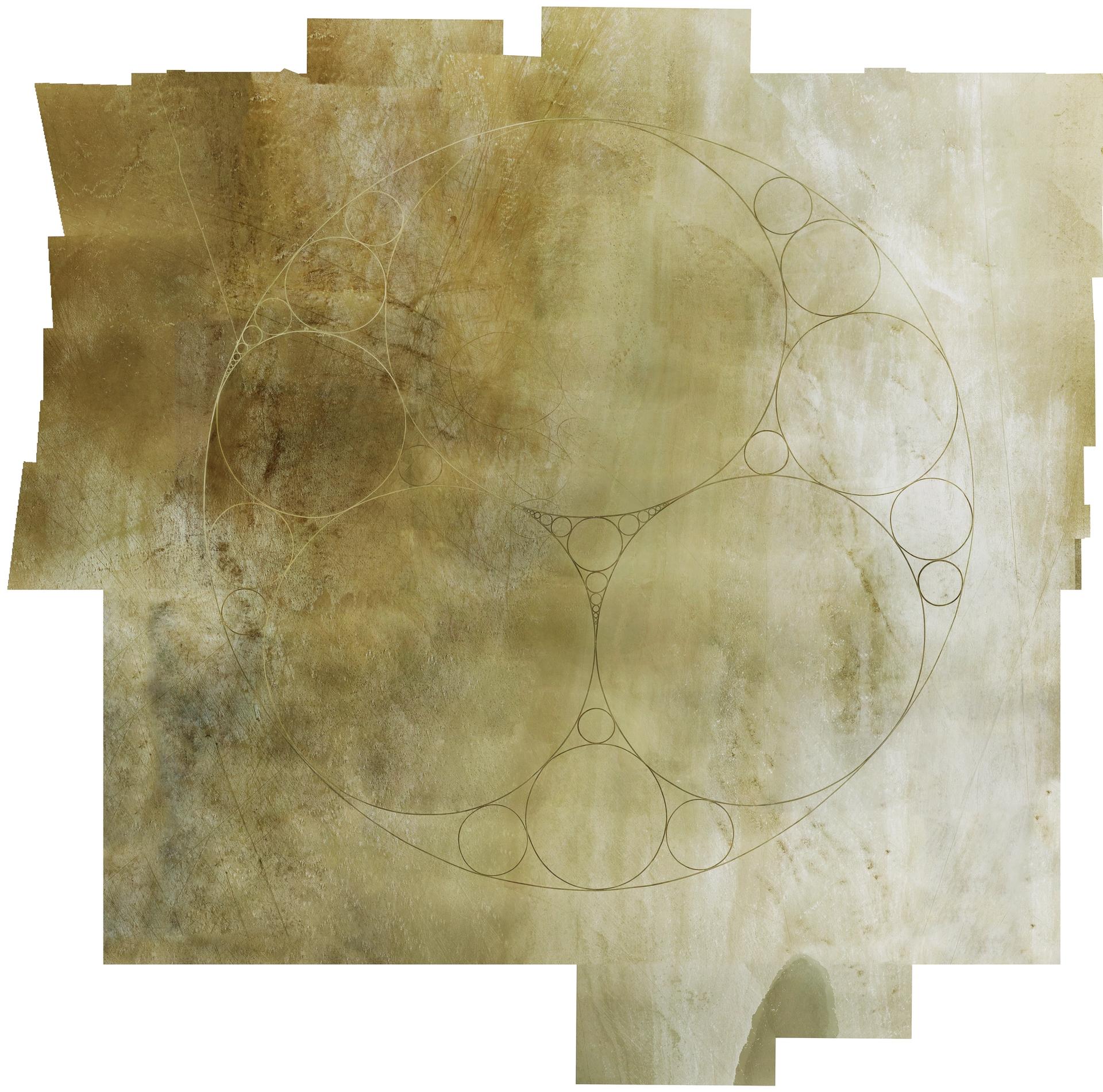

I was curious about what was possible but I still enjoy both equally. One day I was doing a series of spirals and another day I was doing a figurative drawing and someone came to me on the latter and asked: “Where’s that fantastic spiral?” It’s an odd thing to create work in a public space, where it’s always visible, and observe people’s desire to be critical or appreciative. The work relates to the Fibonacci sequence and what some people would call “sacred geometry”, although for me it’s a pure form of meditation. I don’t need to goose it up by calling it “sacred” because it is just naturally that.

Your works are extremely linearly precise. It almost seems impossible to have made them without an aerial vantage point.

People often asked me whether I would run to the top of the cliff and then run back down to check my work, but basically there’s never any checking of the pieces from above. The composition is very coherent and precise as a result of the motions that I’m making on a flat surface. There are no drones, no renting helicopters, although some of the work has been photographed with these tools and even satellites. Geometrical compositions are limited in the fact that you need to see them from above.

Among Denevan's largest installations was the Apollonian Gasket (2009) in Nevada's Black Rock Desert. With a total circumference of over nine miles, which was recognised by the Guinness World Records as the world's largest single artwork, although his 18 square mile 12.5sq mile spiral of circles along a fibonacci curve that he etched onto the frozen surface of Lake Baikal in Russia in 2011 was larger. Installation of Jim Denevan, Apollonian Gasket, Black Rock Desert, NV (2009). Courtesy Jim Denevan.

So much of your work was never documented. The ephemeral nature of the pieces is an inherent part of the work.

When I started, I was simultaneously presenting work that was gigantic and also made in environments where there weren’t many people around. I would generally go to beaches where there were no people. I was very relaxed about it, in the sense that I felt I had discovered something that I could explore that other people hadn’t tapped into yet. There wasn't anyone else that was spending every low tide drawing on the sand. I didn’t have to compete against other artists. The pieces are grand but also fragile because it all disappears. I would feel somewhat uncomfortable creating work in an environment where it took up too much space. It’s all imbued with this attention to transcendence.

The works are philosophically similar to Buddhist sand mandalas.

Yes. I read a lot about Buddhism and Eastern philosophy in my twenties. I’m curious about the various considerations of one’s place in the universe both personally and spiritually. I’m also intrigued by the idea that those things are personal. My meditative motions have realised these compositions. The ratio of the works also has a cosmic significance.

What is your process for creating a piece?

I made some rules for myself at first, including that the drawings would be freehand and that I would use only a stick. I always threw away the stick. Sometimes it washed up on the beach the next day and I used the same stick, but it was always thrown away again. I would go down there with nothing, find the stick, make the composition and sometimes take pictures and sometimes not—but always throw away the stick. I’m in no hurry to become “good” at or master a drawing. I handle it very slowly and even just the walking and the physical part of the process becomes as interesting as the visual result. The physical motions are just as significant as what might be seen from a finished composition.

Denevan working on a piece in Mundaka, Spain. Photo: Patrick Trefz. Courtesy Jim Denevan.

You premiered your largest work to date in 2011 in Lake Baikal, a piece that spanned nearly 20 miles comprising a series of circles drawn on the frozen lake. What was that process like?

I faced challenges with the weather there. The idea was that the snow was like the desert. I pushed the snow off the black ice. The lines are only around six feet wide, so you couldn’t see the composition until you were close to it. It’s a composition that can’t be communicated that well in its entirety in a book or magazine because the width of the line is such that you have to zero-in on it.

It made me think about what other large compositions are out in the world; there’s the Marree Man in Australia, the Palm Islands in Dubai and other colossal marks on the earth. I just thought: “I’m going to make the world’s biggest one.” It was entirely walked, with no vehicles used. The circles are quite imperfect, but tolerances are greater for something that is extremely gigantic. I think I walked hundreds of miles but I don’t like to be precise about that because I don’t have a pedometer. Measuring or gridding obsessively is annoying and I do not want to do that.

You’ve mentioned becoming quite emotional after completing a work, especially some of the larger pieces you have made.

There’s an equal aspect of mental concentration and physical action that goes into it. I figured out that I could make extremely large, semi-accurate circles that could sometimes be an hour and a half walk. I would be walking toward the sun or the mountains, and then I would arrive at the same place that I started. To spend the entire time deeply concentrating and walking and being extremely focused, then to see that initial mark, is almost overwhelmingly emotional. It’s never a fully accurate circle, but in some sense it doesn’t have to be, because you always arrive at the same place.

- Man in the Field: The Life and Art of Jim Denevan is available to stream from Apple TV, Amazon and other digital video services.