The idea of the knight is embedded in our cultural imagination. Chaucer’s “Gentle Knight”, forever “pricking on the plaine”, continues to shape our understanding of the medieval world. This collection of 15 essays, each by a different author—from the opening chapter “From War to Spectacle” by Richard Barber (University of York) via “Jousting under the Holy Crown”, covering the 16th-century Hungarian royal court, by Borbála Gulyás (Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest), to the “21st-Century Knight” by Tobias Capwell, jouster and curator (Wallace Collection, London)—opens up a subject that, as these chapter headings suggest, extends considerably beyond the 11th-century origins of the knightly sport of the tournament.

Indeed Tournaments: A Thousand Years of Chivalry provides a welcome antidote to the tendency for scholars of chivalric culture to announce the decline and death of their subject. Several chapters focus on changes to the form and function of the tournament over time, with Barber exploring its emergence as a practical preparation for war swiftly transforming into something much more complex, combining sport and storytelling with sociable bonding. Discussions of the development of arms and armour across the Middle Ages trace how the tournament at first reflected and then deviated from warfare. From the outset, tournaments were integral to the politics and diplomacy of the court, as shown in chapters on France, across the territories of the Habsburgs and in the Ottoman Empire.

Tournaments provided occasions for spectacle, music and the intricate art of equestrian ballet

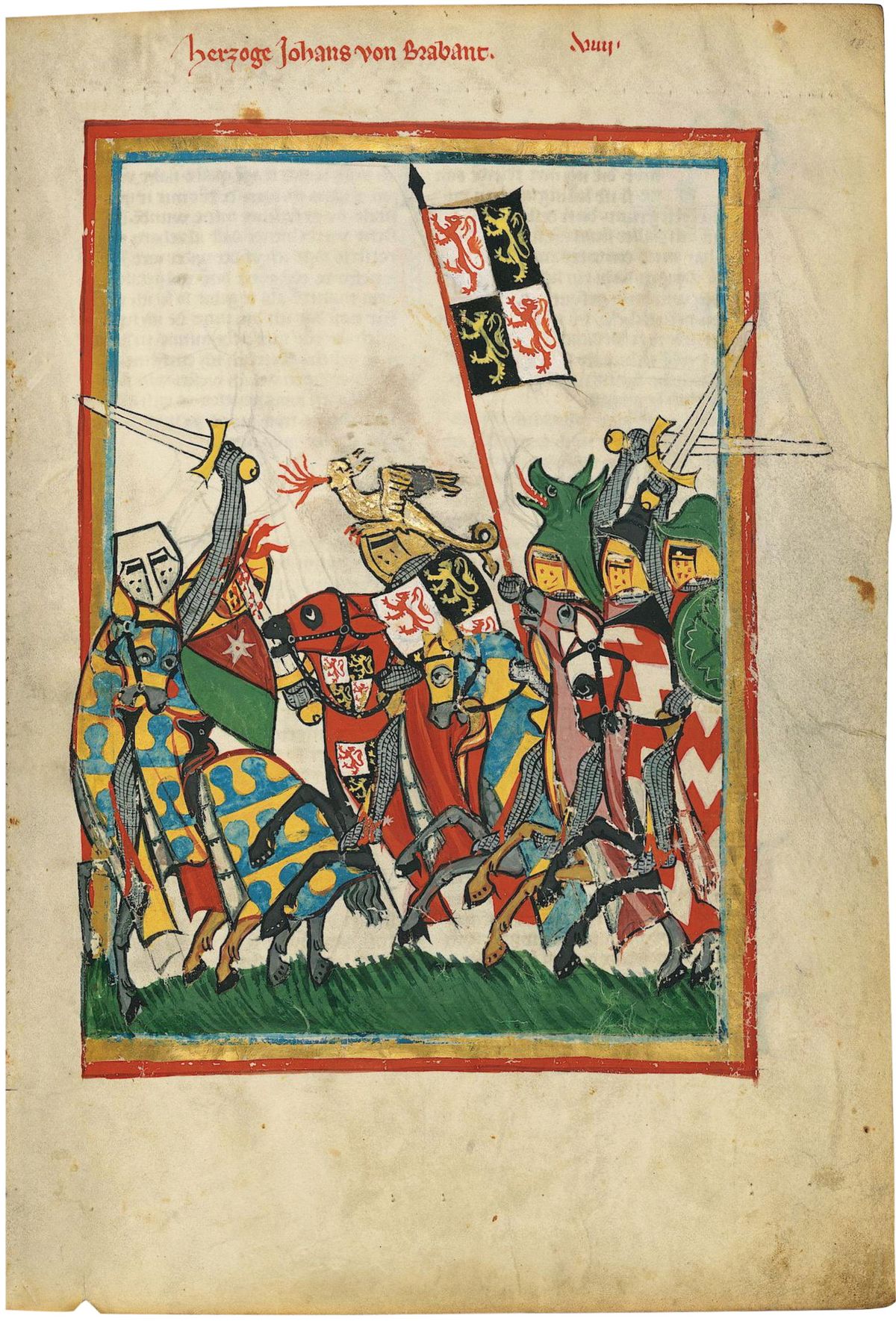

Courtly tournaments provided occasions for spectacle, music and the intricate art of equestrian ballet, discussed by Marie-Louise von Plessen (“Dancing with Horses”). They also formed a central aspect of aristocratic identity, shown in a striking portrait of the Tudor aristocrat Peregrine Bertie, Lord Willoughby de Eresby reclining in his bespoke suit of Greenwich armour. Tournaments is splendidly illustrated, with brightly coloured manuscript illuminations appearing alongside glowing photographs of grimly functional chunks of metal, with the jagged edges of a coronel lance head giving an idea of the physical force of the joust. The gory hand injury suffered by Capwell while jousting at a tournament in 2012 demonstrates how knowledge and expertise can only limit the risk of riding against an opponent armed with a solid wooden lance.

A sallet (light helmet) from the 1520s that belonged to of Louis II, King of Hungary and Bohemia Metropolitan museum of Art, New York

We learn that parasols were used to shelter armoured men in the 16th century

There is great delight in the detail, such as the symbolic intricacies of the sash or “band” worn by members of the Castilian Order of the Band (established 1332) conferring talismanic properties on the field of battle as well as denoting membership of a “courtly brotherhood”. The rules of the Order—the first to be written and codified for tourneys and jousts in Western Europe, as described in Noel Fallows’s chapter—include guidance on foods to avoid in the interests of good health, notably “foul and base fruits and vegetables”. We learn that parasols were used to shelter armoured men in the 16th century, preceding their inclusion in satirical lithographs depicting the fictional character Lord Farcington in the French journal La Mode in 1839.

For anyone who has struggled to make sense of the displays of armoury in museums and historic properties across the world, the book sheds considerable light on the form, development and functionality of these objects. They are shown to be beautiful, with intricately worked decoration highlighting the connection between violence, display and identity. A 16th-century sallet (light helmet) bearing the interlinked initials of Mary of Hungary and her husband Louis II Jagiellon, rescued from dusty obscurity as photographed in 1920 within the former imperial arsenal in Istanbul, gleams from its present-day home at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Illustrations from Freydal, the tournament book commissioned by Emperor Maximilian I in the early 16th century, provides a welcome reminder of the excellent exhibitions staged in New York, Innsbruck and Augsburg in 2019 to commemorate the 500th anniversary of his death.

Revival and re-enactment

A more nostalgic atmosphere emerges in Jonathan Tavares’s account of the Eglinton Tournament held at Eglinton Castle, Scotland, in 1839, where just six hits were recorded on the second day. Tournaments continued to be associated with ideas about national identity, with efforts to revive the sport in the 19th and 20th centuries throughout Europe and the US. Nicolas Baptiste’s chapter on early 20th-century Belgium shows how their Burgundian heritage was used to generate national identity through historically themed pageants and carefully staged re-enactments of past tournaments featuring Maximilian, Henry VIII and Francis I.

Readers may find the inclusion of a single appendix and the absence of an index confusing, and certainly the latter makes the book hard to navigate for anyone seeking to draw connections across chapters. A longer introduction might have helped to frame expectations, and no subject of this scope can be covered in its entirety in a single volume. Nonetheless, Tournaments is a rich collection that demonstrates the potential of international collaboration between scholars, curators and conservators and makes a distinctive contribution to the subject.

• Stefan Krause (ed.), Tournaments: A Thousand Years of Chivalry, Thomas Del Mar, 278pp, 131 colour and 40 b/w illustrations, £85 (hb), published 28 March

• Janet Dickinson researches the history of the court and elites in early modern Europe. She teaches for the Department for Continuing Education at the University of Oxford and for New York University in London