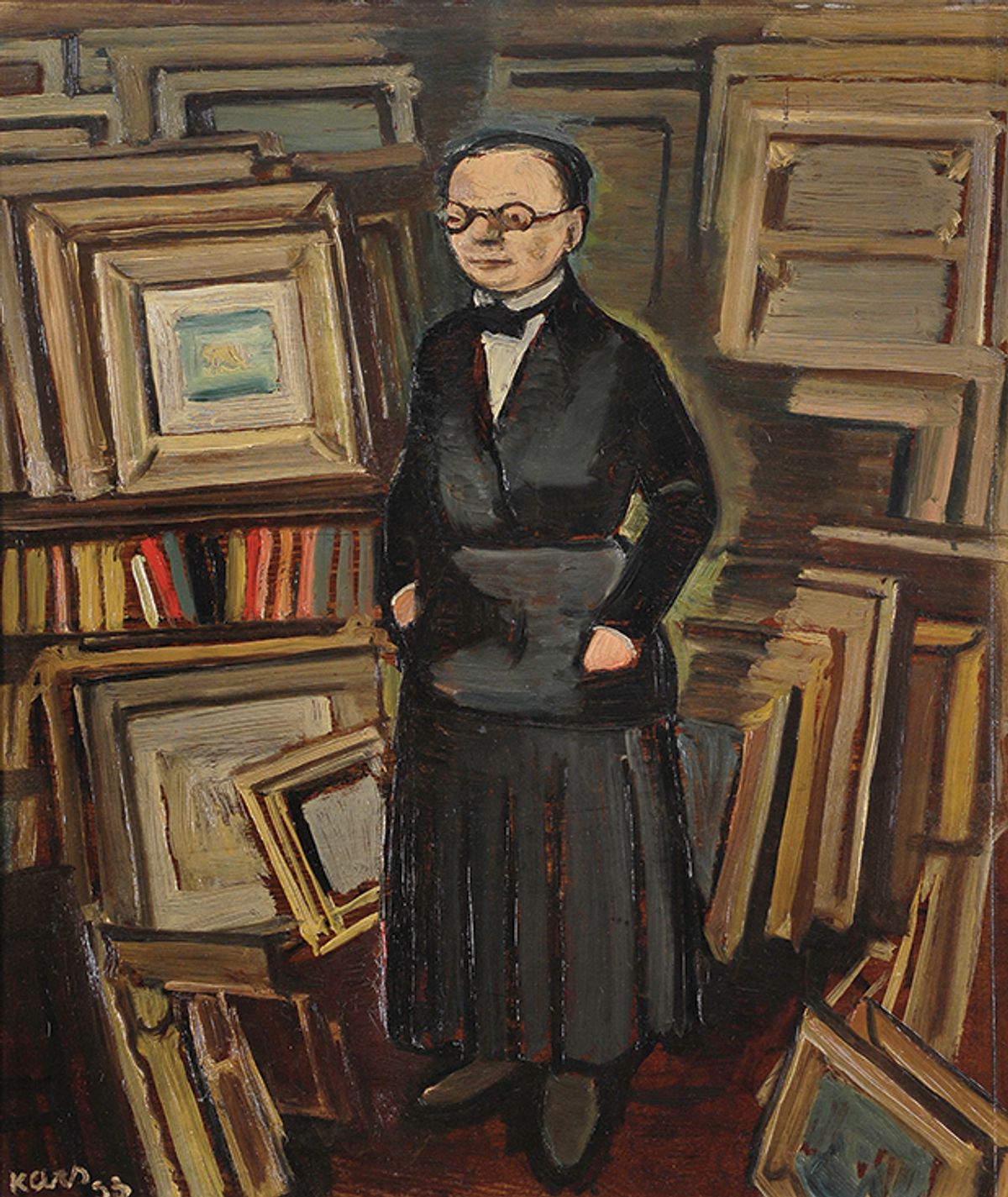

The memoir of the pioneering Parisian dealer Berthe Weill (1865-1951), originally published in 1933 as Pan! … dans l’oeil! … ou trente ans dans les coulisses de la peinture contemporaine 1900-1930, rockets along with astonishing energy reflective of her own dynamism. In projecting the reader through rather more than 30 years in the art world, Weill marshals a mass of detail, clearly culled from her stock books and her diaries that must have been to hand as she wrote.

The fact that it is the first English translation is perhaps not surprising, as the difficult text matches what Weill herself called her “music-hall-style” of writing, a bantering engagement with a knowing audience now only made comprehensible to most readers by the critical apparatus supplied in this edition.

Weill’s considerable achievements have languished in relative obscurity, despite the memoir. She should be a familiar name; she supported the unknown Pablo Picasso and his Barcelona colleagues around 1900, she showed the equally struggling Henri Matisse and the Fauves soon after, and—probably the most familiar story—gave Amedeo Modigliani his only lifetime exhibition (immediately closed by the police chief who lived opposite and who objected to the nude showcased in the gallery window).

As important at the time, and a salutary reminder today, was her consistent inclusion of the work of the women artists of the avant-garde throughout the existence of her gallery, including Emilie Charmy, Marie Laurencin, Jacqueline Marval, Valentine Prax and Suzanne Valadon. Such support for the soon-to-be-famous, as well as those women whose reputations continue to be eclipsed by their male counterparts, shows Weill’s perceptive eye and

generosity of spirit, conveying how survival as a dealer to the avant-garde proved a relentless struggle. As an unmarried Jewish woman art dealer, she was triply marginalised and her memoir addresses the racism and misogyny within the precarious world of Parisian Modernism in a period of speculation and financial instability.

Among the questions that recur in reading Weill’s text is how the characters who are exposed to her occasionally caustic tongue reacted to its publication in 1933. Many probably revelled in the account of their youthful exuberance but some (like the painter Maurice de Vlaminck, whose pomposity is satirised) may have found it difficult to forgive. Most curious is that the original edition was prefaced by an ill-judged critique of fellow dealer Ambroise Vollard; the English edition removes this article to an appendix, allowing the reader “to dive headfirst into Weill’s lively saga”, as the editors put it.

If the uncertain response of her contemporaries comes to mind, Weill’s book is also a reminder of the fragility of notoriety, success and fame. For every familiar name there are a dozen she expected her readers to recognise but who have fallen into obscurity. By bringing her own account to an English-speaking volume, the editorial team help Weill to regain the place she established for herself. As the scholar Marianne Le Morvan hearteningly reveals in her introduction, in old age Weill’s by-then successful artists repaid that early confidence by donating to an auction, the proceeds of which supported her in later life.

• Berthe Weill, edited by Lynn Gumpert, translated by William Rodarmor, introduction by Marianne Le Morvan, foreword by Julie Saul and Lynn Gumpert, Pow! Right in the Eye! Thirty Years Behind the Scenes of Modern French Painting, University of Chicago Press, 280pp, 12 half-tone illustrations, $22.50/£17.89 (hb), published 14 June

• Matthew Gale is an independent art historian and curator, formerly senior curator at large, Tate Modern