Blaise Cendrars—the Swiss poet with one arm who was born under the name of Frédéric-Louis Sauser—is an unsung hero of European modernism. Cendrars apparently lost his limb fighting with the French foreign legion during the first world war, one of many colourful details in the life of this little known polymath who collaborated with key artists such as Fernand Léger and Sonia Delaunay.

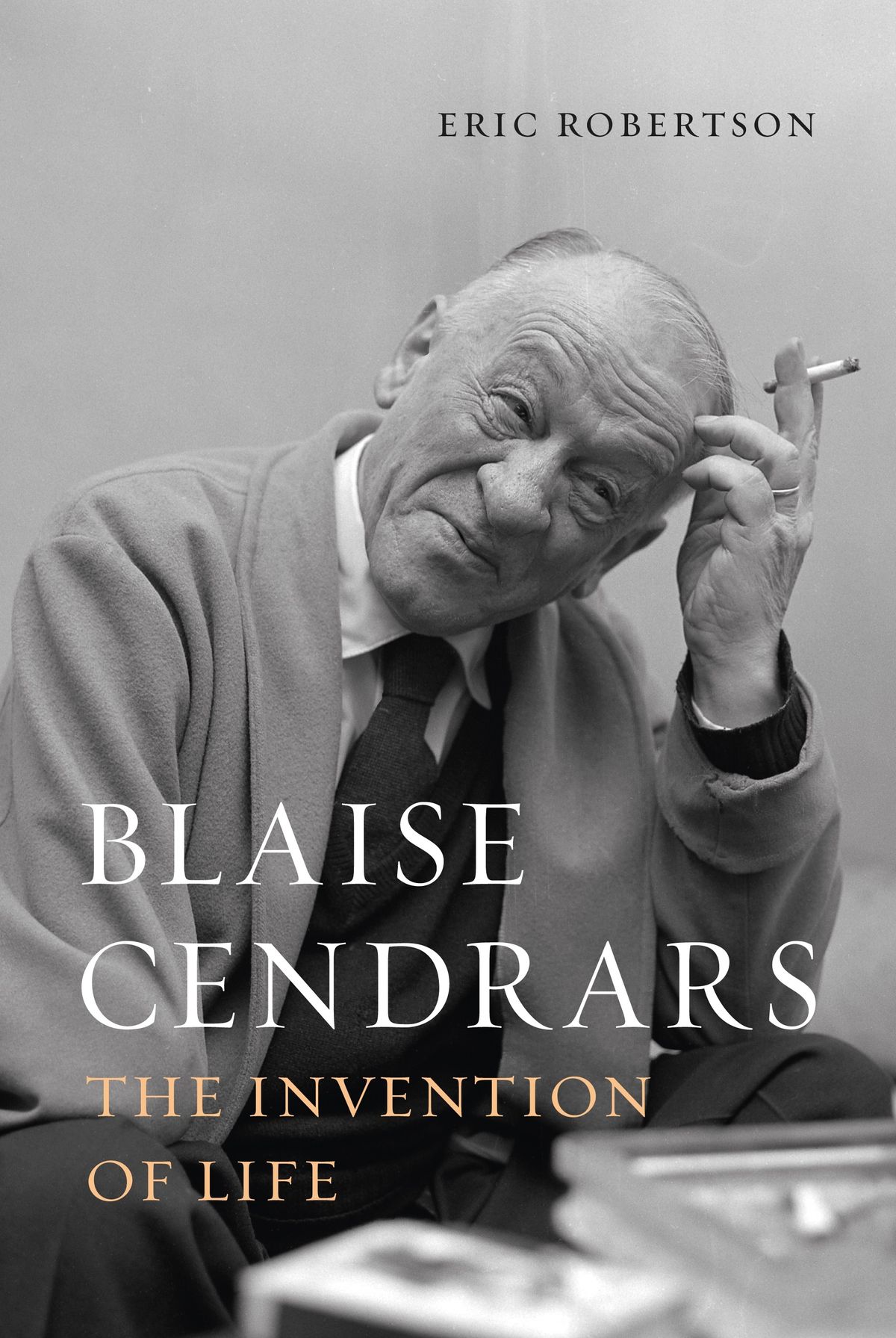

The Invention of Life, a new publication by Eric Robertson, professor at Royal Holloway (University of London), re-evaluates this revolutionary writer of the early 20th century who was plugged into avant-garde art and literature. “Engaging with Cendrars can be an overwhelming task; indeed, at times it seems implausible that a single individual could live as eventful a life as he did and somehow find the time to document it so extensively in writing,” says Robertson.

“[The publication] will also consider some of his creative collaborations with painters, cinematographers and photographers and will assess their impact on his writing as well as considering the influence of other writers on his work.” Here are three “takeaways” from Robertson’s scholarly new analysis (disclaimer: I studied Cendrars under Robertson for my doctorate).

-Cendrars created one of the first artist books: La Prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France

An excellent starting point for an investigation into the relationship between visual and verbal modes of expression in Cendrars’s work is La Prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France (1913), a poem based on recollections of a train journey eastwards from Moscow on the Trans-Siberian railway. Cendrars teamed up with the artist Sonia Delaunay who produced a twenty two-panel illustrated piece to accompany the literary work, transforming the traditional book format into an object that unfolds accordion-style.

The arty poem was “billed audaciously by Cendrars as ‘le premier livre simultané (the first simultaneous book)… not only is [the text] intended to be read and viewed simultaneously, but indeed the text itself is built upon a series of spatial, temporal and stylistic juxtapositions,” writes Robertson. “Upon opening it, our first impressions are confounded, both by its heterogeneous appearance and its patchwork of textual and visual elements.”

Robertson reveals that on lifting the original colour sleeve, made of card and adorned with Delaunay’s geometric colour washes, we discover a route map indicating the train journey from Moscow to Harbin in northeast China. The Victoria & Albert Museum in London owns a copy of La Prose signed in blue ink and numbered in red ink '111' by Blaise Cendrars.

-Cendrars’s closest and most lasting artist friend and artistic collaborator was Fernand Léger

Cendrars had an affinity with the French painter and sculptor Fernand Léger, a bond exemplified in the closing poem of the collection Dix-neuf poèmes élastiques (Nineteen Elastic Poems, 1919), which “reflects the diversity of the modern world and celebrates everyday life”, writes Robertson. Léger’s industrial imagery is exalted in the poem Construction, “the cloudy geometry” of his art brought to the fore in the punchy syntax of the verse.

The most significant joint work produced by the pair is J’ai Tué (1918), a short text that conveys the influence of cinema. Robertson describes how three days before the armistice, on 8 November 1918, the text was published as an illustrated book with colour lithographs produced by Léger who was recovering from war wounds. Cendrars was heavily involved alongside the publisher François Bernouard in overseeing the typesetting and printing process at the latter’s publishing house, à la Belle Edition.

A cinematic perspective underpins the vision of both men. “In their fragmentation and so-called ‘tubist’ style, [Léger’s] illustrations reflect the same principle of montage that characterises the structure of Cendrars’s text, which presents a fast succession of juxtaposed points of view. These contrasts offer the reader a series of radically diverse perspectives on the action, rather like the mobile eye of the camera,” Robertson says.

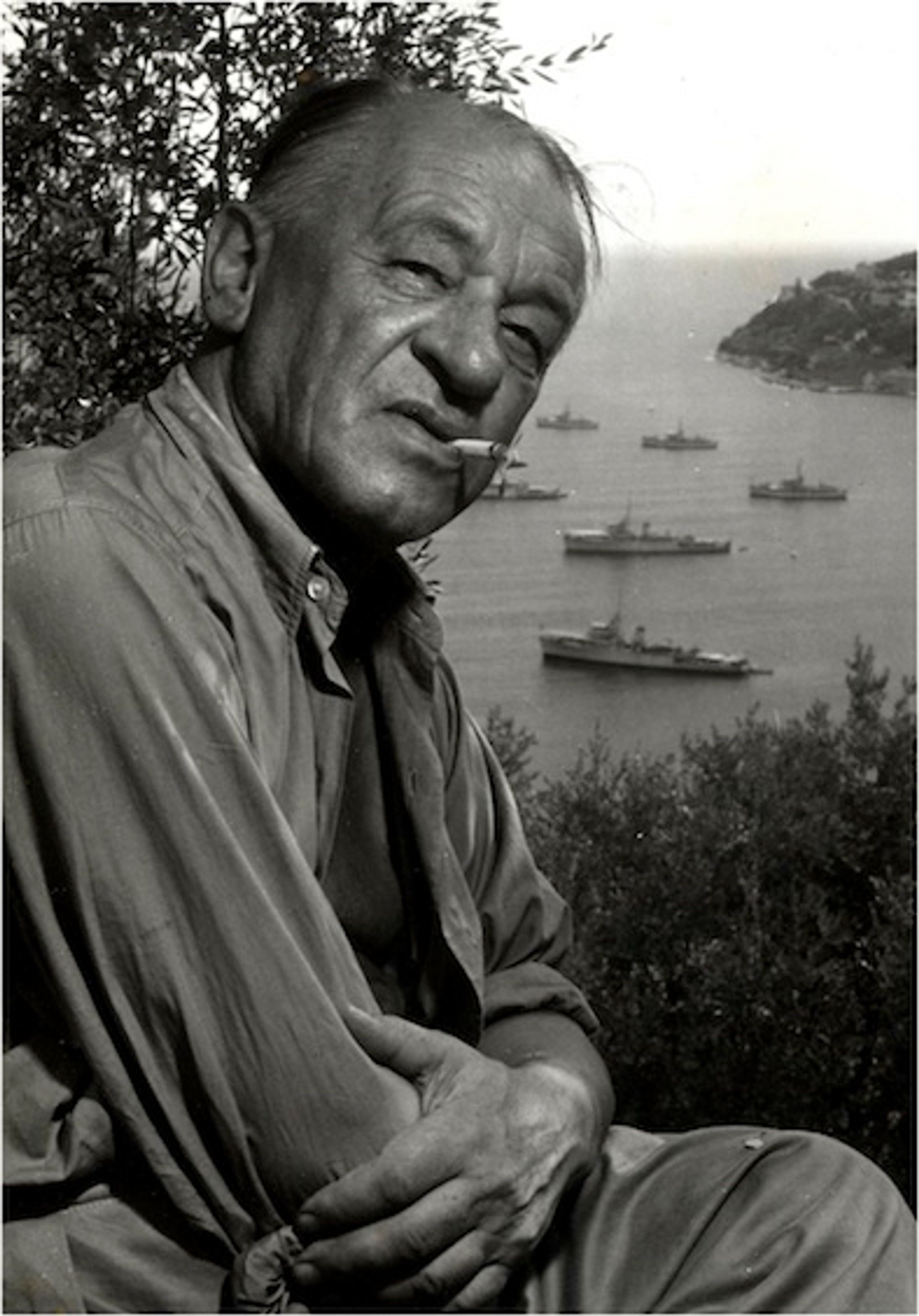

Blaise Cendrars. Photo: Robert Doisneau

-Cendrars helped to launch the career of the French photographer Robert Doisneau

Robert Doisneau is known for his ultra-romantic image Le Baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville (The Kiss by the Hôtel de Ville, 1950) but the photographer previously had a helping hand from Cendrars. The pair collaborated on La Banlieue de Paris (The Suburbs of Paris), a text accompanied by Doisneau’s photographs of austere, post war working-class Parisian neighbourhoods.

“Towards the end of the first section [“South”], Cendrars turns to Doisneau, his work and photography more generally. He also considers its distinctive qualities compared with literature: for Cendrars, photography is a more effective means of capturing the humanity of its subject,” Robertson writes, considering how Cendrars muses on the camera’s penetrative gaze.

The first section ends with the poet’s reflections on modern-day society and previous eras. “Cendrars returns to the medieval era and the construction of cathedrals, noting that Doisneau’s photographs are redolent of that historical period. Commenting on one of Doisneau’s photographs depicting a manual worker, he likens the photographer’s actions to those of a thief, intent on pursuing his target.”

Doisneau’s image of a dishevelled boy working along a road in Aubervilliers, Le fils d’Israël d’Aubervilliers (1949), draws an optimistic response from Cendrars. “[…] the tyre tracks on the road, to which Cendrars draws the reader’s attention, embody the free spirit of the bourlingueur (adventurer) and the insatiable desire to explore the world, even if that world is fundamentally hostile,” Robertson observes.

Blaise Cendrars, The Invention of Life, Eric Robertson, Reaktion Books, £25.00, 328pp (hb)