While most Shanghai-based artists have waxed introspective during the hard Covid-19 lockdown that has suspended the city of 26 million inhabitants since 1 April, artist Gao Jie has, since day 18, been documenting in simple, expressive drawings the period’s daily absurdities and indignities. Softer mundanities like endless nucleic acid and antigen testing, or the scramble to obtain food, are punctuated by unsanitary quarantine centres, mass removals of neighbourhoods, and violence by the white hazmat suit-clad enforcers, called Dabai or Baymaxes. Videos and photographs of abuses go viral among a rapt, captive audience before being, mostly, censored from social media.

“The shock from all the chaos today is far more powerful than any work of art, film or literature,” Gao says. “Dealing with immediate pain, with the daily imminent danger” of testing positive or being quarantined due to proximity or clerical error, “has become intrinsic to being Shanghainese and Chinese. The information society means that everyone sees ever more videos of the suffering of people around them, the recordings of arguments between intellectuals and law enforcement, the videos of physical conflicts.”

Gao was born in Xiamen, studied at the School of Fine Arts in Le Mans, France, and is based in Shanghai; he had a solo show last year at the ShanghART Gallery in the city. His work was also shown at the ninth Shanghai Biennale (2012-13) and at Tang Contemporary Art in Beijing in 2013.

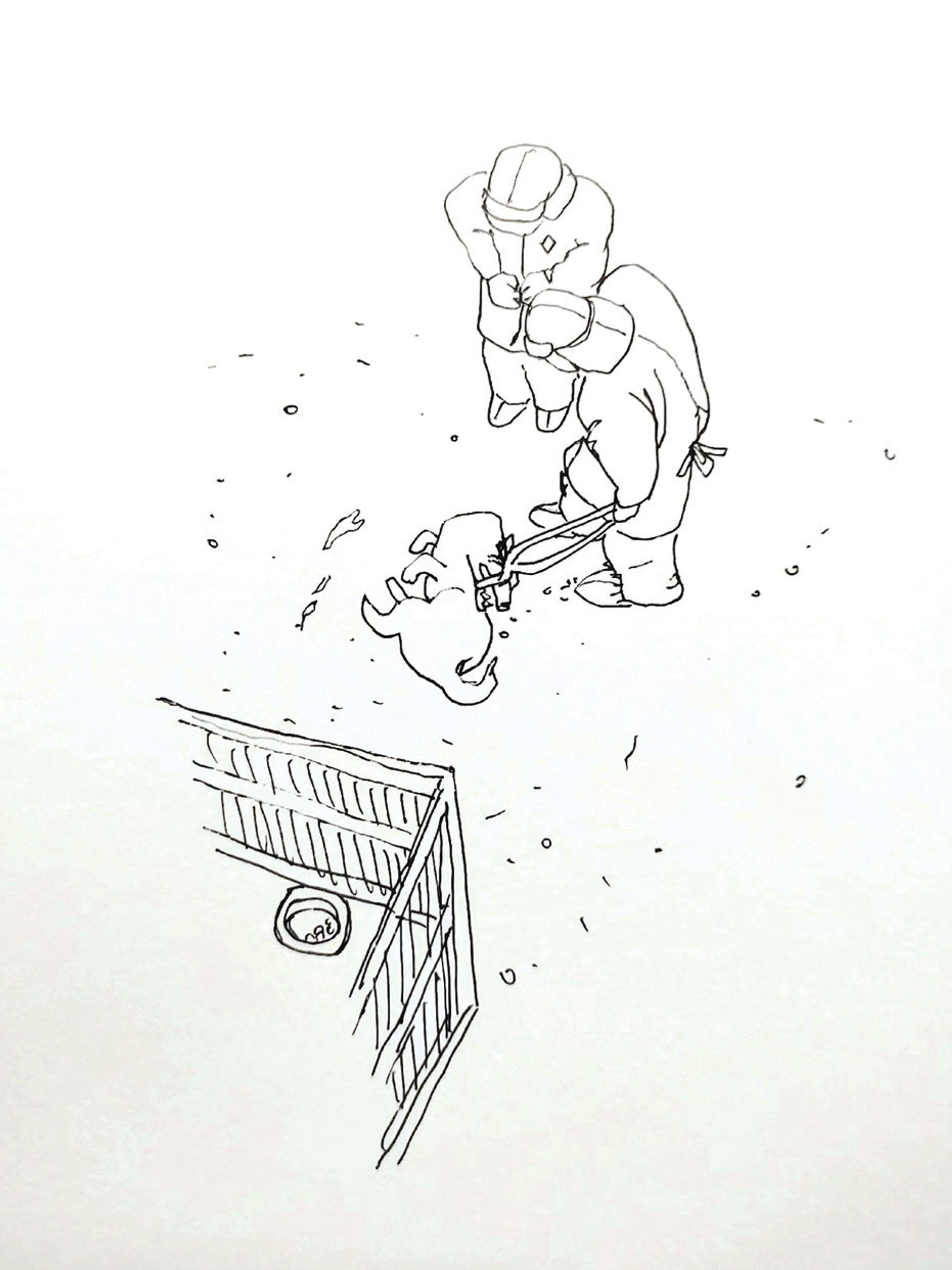

Gao Jie’s Beaten Dog (2022) © Gao Jie

He began the Covid project after the most recent lockdown, originally announced as lasting four days, started dragging into weeks. He was stuck at home after his wife, curator Chao Jiaxing, had smuggled herself to the airport and out to Venice. “I found myself in a very embarrassing situation: I lacked food and couldn’t even go to the corridor,” he says, let alone obtain painting materials. All he could find at home was a packet of drawing paper.

‘Morality in resistance’

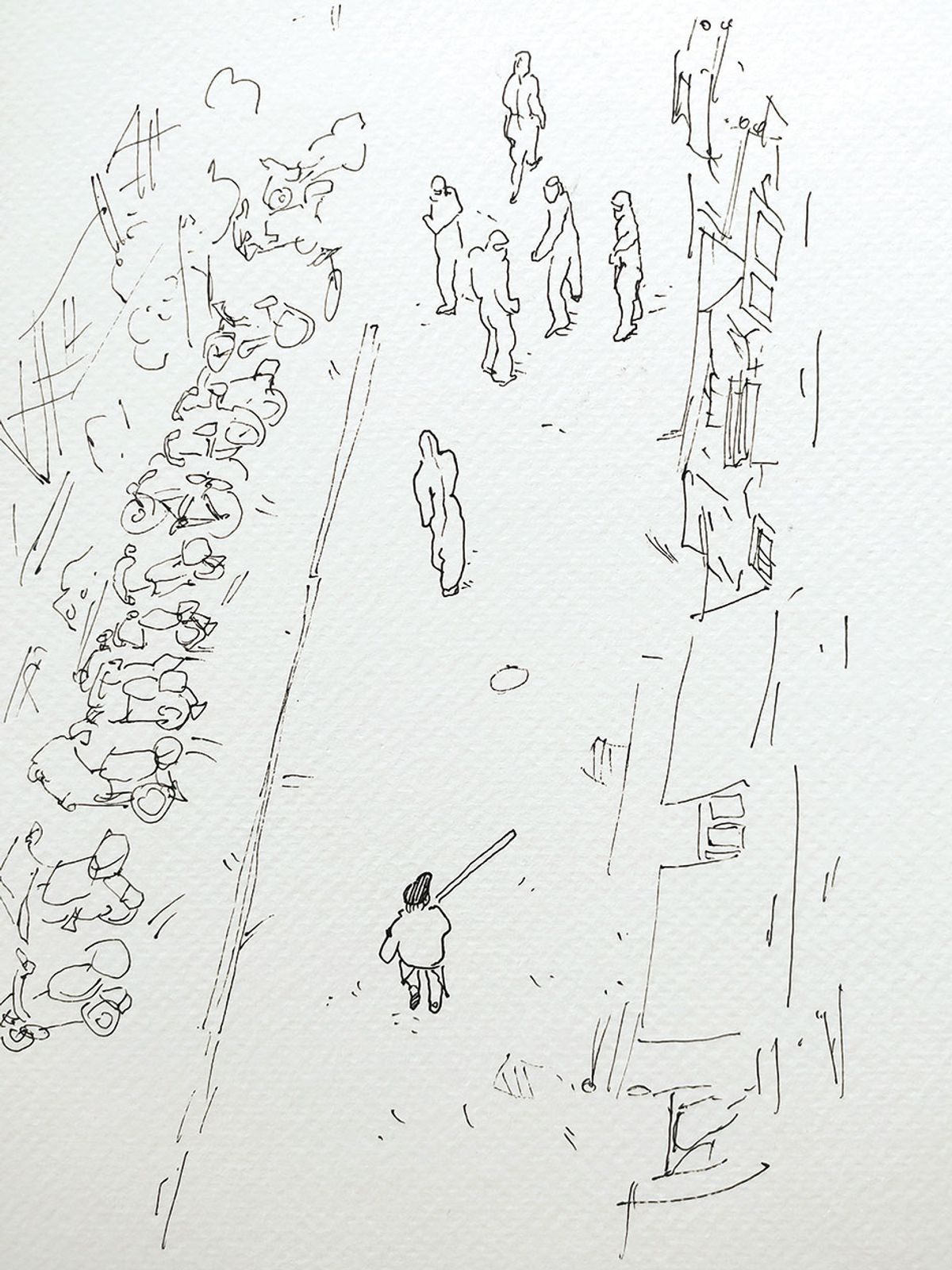

More than 200 drawings to date include Old Lady, portraying a woman, possibly mentally ill, who defied stay-in orders and resisted arrest, fending off several Dabai with an iron bar. “A person who was very weak in the past society becomes very strong at this time,” Gao says. “Confronting absurdity with absurdity almost creates a kind of normal. Chinese culture traditionally views those who violate martial law as chivalrous: there is a sense of morality in resistance to rules, so she seemed to me more legendary than a [a hero in a] big action film.”

I drew countless absurd and extremely stupid things being done by Dabai [suit-clad enforcers]Gao Jie, artist

Another work, Beating a Dog, depicts an incident in which Dabai beat an animal as its owner was removed to central quarantine. “There were so many images like this, and I draw them every day, though mostly it’s people” being mistreated, Gao says. “I drew countless very absurd and extremely stupid things” being done by Dabai, “many even more absurd than this one”. Hazmat-suited figures have been captured doing everything from harvesting vegetables, alone in a field, to packing a residential stairwell with barbed wire to climbing into homes to spray disinfectant into refrigerators and over rooftops.

A widely reshared video depicted a team of Dabai police breaking down and climbing through the door of an apartment to take its residents to central quarantine, despite their protestations that their Covid tests had all been negative. “There are countless similar incidents every day,” Gao says, with “countless people ordered to leave home and go to quarantine centres, though many of them think their nucleic acid test results are wrong”.

Another incident involved a middle-aged man who died at home during lockdown, his body uncollected for days even as food rations piled up outside in the hallway, attracting cockroaches. “This half-closed door is more terrible for me than the direct presentation of the body,” Gao says. “Behind this door may be you, me, our family or neighbours. Behind this door is a very real, complex and ordinary story. This door reminds me what kind of world I live in.”

As Shanghai’s lockdown drags through month two at the time of writing, with a heralded official June reopening rendered nearly meaningless by a catalogue of restrictive caveats, the unease Gao documented has spread to Beijing and the rest of China. He has not formulated any plans for the series, which might be challenging to exhibit or publish within the country.

“I just hope that in ten years, I can see a small dusty drawing on a small wall above the shoe cabinet at the entrance of my home, reminding me not to forget my current self peeping through the cracks of 2022,” Gao says. “I hope I will never forget. ‘Forgetting’ makes people stupid.”

The artist concludes: “History tells us that Chinese people will forget their wounds at the moment of change. Amnesia is the most obvious, widespread and serious disease of the

information age.”