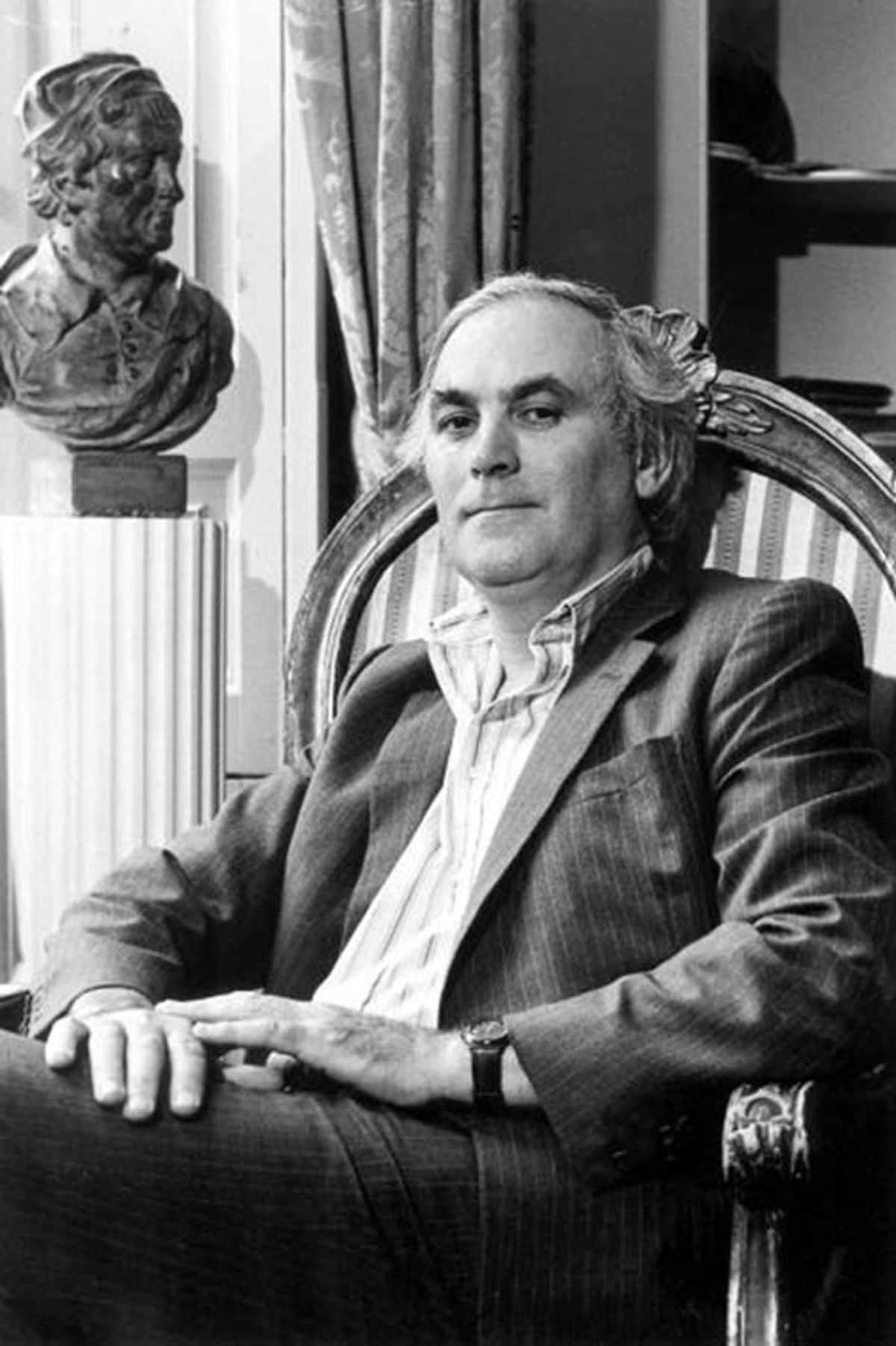

The distinguished architectural historian John Harris, scion of a dynasty of upholsterers, spent his early years in a dim semi-detached house in suburban Cowley, on London’s western fringe. The rebellious child found solace in his bachelor Uncle Sid, whose passion for fishing, for archaeology and literature, and for exploring country estates was an inspiration.

Leaving school in 1945, aged 14, Harris was shoe-horned into the upholstery department at Heal’s but soon earned the sack. Short-lived jobs alternated with wanderings in search of country houses, until in 1949 National Service conveyed him to Malaysia, where he wangled an involvement in archaeology, rose to sergeant and made money from a kerosene scam. This bankrolled him in 1952 to Paris and the Ecole du Louvre, a dull disappointment compensated by an entrée to the diplomat and connoisseur Richard Penard’s treasury of dix-huitième art and Harris’s own lively démarches, including a sortie into the then impregnable garden at Désert de Retz, west of Paris.

Back in London in 1953, his initiative and brio, a certain piratical allure and plain good luck brought friendships with many serious—and not so serious—players in architectural and decorative arts history, including Francis Watson at the Wallace Collection; Howard Colvin, the lexicographer of British architects; Rupert Gunnis, his hospitality as legendary as his knowledge of British sculpture; and Geoffrey Houghton-Brown, an antiques dealer with a brilliant eye. Harris worked for Houghton-Brown until, in 1956, an introduction from James Lees-Milne led him to the library of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), one of the world’s greatest collections of architectural drawings.

Harris thanked the local constabulary for not arresting 'a very suspicious black-hatted character lurking around buildings until twilight'

In 1959, he was asked by Nikolaus Pevsner to collaborate on The Buildings of England: Lincolnshire (1964). In his foreword, Harris thanked the local constabulary for not arresting “a very suspicious black-hatted character lurking around buildings until twilight”. During this period he honed his ingenuity in infiltrating houses, a lifelong amusement and challenge. And in 1960, not yet 30, his life was transformed by his appointment as the curator of the RIBA drawings collection and marriage to his American wife, Eileen Spiegel, the author of definitive works on Robert Adam and on British architectural books and their writers.

Eventually, in 1970, Harris secured new premises for the drawings collection in Portman Square, next to Home House, by James Wyatt (as Eileen discovered) and Robert Adam, the home of the Courtauld Institute. There, in 1972, he opened the Heinz Gallery, an elegant installation designed by Alan Irvine and Stefan Buzás. (The fit-out was happily relocated in 2005 to the Irish Architectural Archive in Merrion Square, Dublin.)

Energetic curatorship

Although Harris’s interests were centred on the 18th century, the 64 Heinz exhibitions that preceded his retirement in 1986 were immensely wide-ranging, including Richard Norman Shaw, James Stirling, Giovanni Michelucci and Carlo Scarpa. But it is worth singling out Silent Cities (1977), curated by Gavin Stamp, on cemeteries of the Great War, a subject near to Harris’s heart, and the pioneering Eileen Gray (1973), curated by Alan Irvine. Thanks to Harris’s energetic curatorship the collection grew apace, and from 1969 to 1984 a model 18-volume catalogue was published, edited by Jill Lever, Harris himself contributing Inigo Jones and John Webb (1972) and Colin Campbell (1973).

All this activity brought architectural drawings into the limelight as never before, and it is not surprising that in 1979 Harris became the founding chairman of the International Confederation of Architectural Museums, of which he was president in 1981 and honorary life president from 1984. Under his aegis, lunchtime at Portman Square, informal, epicurean and noisy, was a convivial and cosmopolitan meeting place and gossip-shop. Its many habitués included John Cornforth of Country Life, Desmond FitzGerald, Knight of Glin, Christopher Gibbs, Mark Girouard, David Watkin, Bill Drummond and Gervase Jackson-Stops. How Harris relished all these personalities, including the gregarious, spluttering American architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock, whom he contrasted in print to the icily controlled John Summerson. With another friend and visitor, Marcus Binney, he created the Destruction of the Country House exhibition, held at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in 1974, memorable for the vast toppling wall of stones bearing photographs of lost houses, which greeted the visitor.

Throughout the decades Harris published vigorously, a constant stream of articles supporting his larger projects. The very early Regency Furniture Designs (1961) remains essential, but it was his Sir William Chambers, Knight of the Polar Star (1970) that firmly established him as a grandee. Chambers and his imbrication with early French neo-classicism (the subject of a lively querelle des savants with the elderly and peppery Ralph Edwards in 1968) was a lasting theme, culminating in the 1996 Sir William Chambers: architect to George III exhibition. Who but Harris, at the time of the great Council of Europe The Age of Neo-Classicism extravaganza in 1972, would have produced and distributed lapel badges proclaiming, in Gothic script, “Neo-Classicism No!”? Inigo Jones and his circle were another constant, the catalogue (1979) of the drawings at Worcester College, Oxford, being succeeded by Inigo Jones, Complete Architectural Drawings (1989).

Badminton House, Gloucestershire. Harris's scholarly research into the house's built history was fundamental to its restoration in 1984-85 for his neighbour David Somerset, Duke of Beaufort, chairman of Marlborough Fine Art

Another string to his bow was revealed in the delectable Gardens of Delight, The Art of Thomas Robins (1976), an introduction to that delightful rococo artist, very much Harris’s discovery, and his A Garden Alphabet (1979) was a sprightly companion to the solider book of the V&A’s The Garden exhibition, which he edited. Harris’s lifelong interests in paintings, architecture and gardens coalesced in his The Artist and the Country House (1979, revised 1985), a massive compilation replete, as Girouard wrote, with “splendid abundance, careful scholarship, pleasures and surprises”.

Harris first entered the public consciousness as the supreme self-declared 'country house snooper' in two electric and episodic memoirs, No Voice From The Hall (1998) and Echoing Voices (2002)

From 1959, partly thanks to Eileen, Harris was a regular transatlantic presence. Many drawings in the Yale Center for British Art bear witness to his acumen as an adviser to Paul Mellon and in 1987 his unsurpassed collection of country house guide books was acquired by the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal, founded by his close friend Phyllis Lambert. His early travels bore fruit in 1971 with the publication of a mighty catalogue of British architectural drawings in no fewer than 42 US collections, public and private, from Connecticut to California. And in Moving Rooms (2007) he chronicled the taste for and trade in panelling and other architectural remnants, which was behind the cult of the museum “period room” and which involved much confusion and deception—irresistible grist for John’s detective skills.

There were many committees and professorships, prizes and honours, but Harris first entered the public consciousness as the supreme self-declared “country house snooper” in two electric and episodic memoirs, No Voice From The Hall (1998) and Echoing Voices (2002).

They present a cast of eccentrics and obsessives, tales of extraordinary discoveries and picaresque escapades, packed with recondite information and suffused by an underlying melancholy at so much loss and destruction, but the dominant tone was nonetheless of an uninhibited relish in the vagaries of experience. This was architectural history in a wholly new guise.

Acerbic, sometimes splenetic, in controversy, a connoisseur and collector with an eagle eye, a lover of good hotels and rich food (red meat, preferably sanglant, truffles, clotted cream and substantial red wines were favoured), and a focus of merriment and laughter, John Harris could not abide earnest bores. His kindness towards young scholars, whom he liked and encouraged, was lifelong. His great scholarly achievements will endure, but his friends will most remember his generosity and sheer zest.

John Frederick Harris; born Cowley, Middlesex, 13 August 1931; married 1960 Eileen Spiegel (one son, one daughter); died Badminton, Gloucestershire, 6 May 2022