Breyer P-Orridge: We Are But One, Pioneer Works at Red Hook Labs, until 10 July

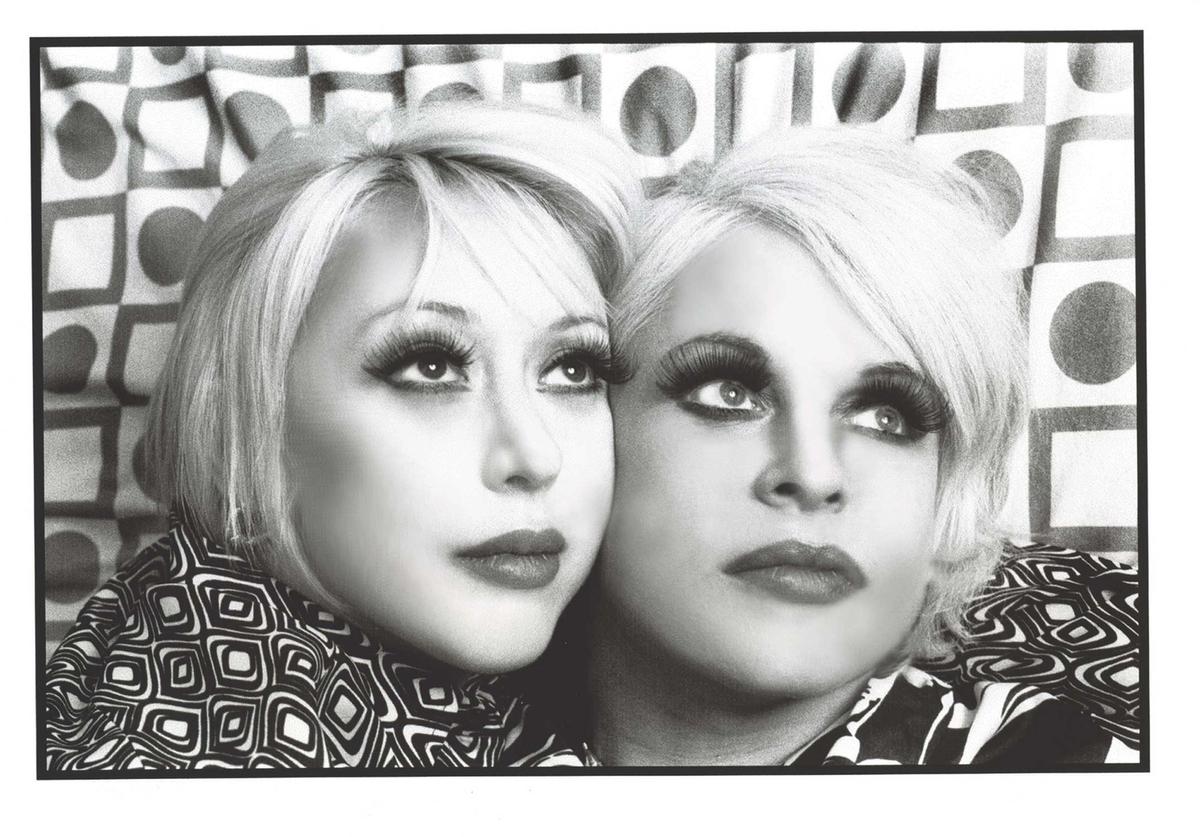

This is the first institutional show of Genesis Breyer P-Orridge’s work since the artist dropped her body—as she would have put it—on 14 March 2020, a few years after getting a terminal leukaemia diagnosis. It is also the first institutional show to focus on what might be the late artist’s magnum opus, the Pandrogyne project. The project involves P-Orridge embarking with romantic and artistic partner Jacqueline Mary Breyer, better known as Lady Jaye, on a series of cosmetic surgeries to look more and more alike, attempting to knock at the door of merging into a singular being that defied categorisation.

The show includes photographs documenting the pair’s physical transformations, images in which appendages from their bodies meld into a singularity, as well as sculptures, drawings, video and collage. The latter was central to the Pandrogyne project. Inspired by the “cut-up” technique championed by William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin—friends and mentors to P-Orridge—collage became an apt metaphor for how to live in the organic, all-encompassing way the Pandrogyne project envisions.

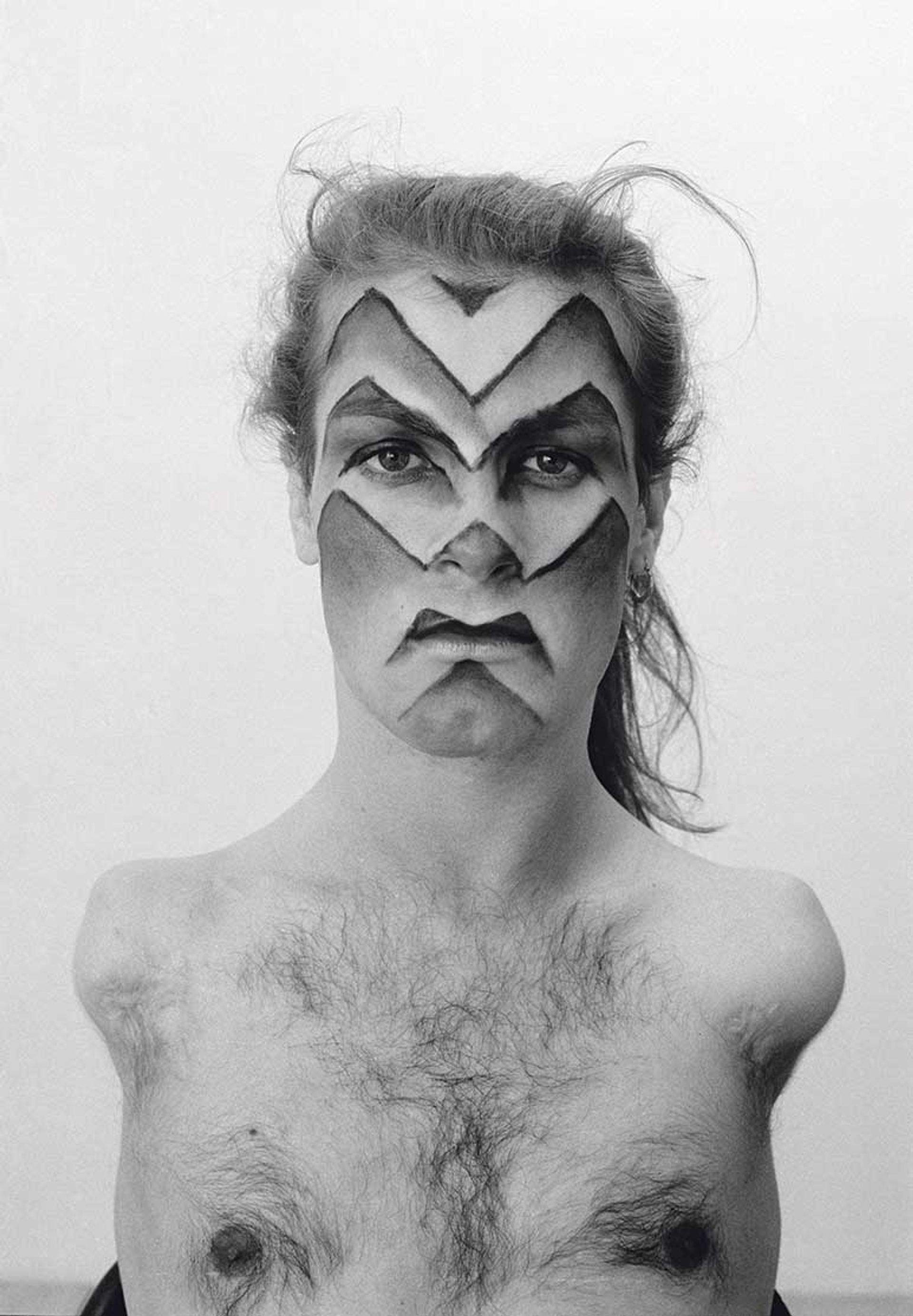

The artist Lorenza Böttner’s work, such as Face Art (1983), challenged perceptions of disabled people Private collection, all rights reserved

Lorenza Böttner: Requiem for the Norm, Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, until 14 August

The late transgender Chilean-German artist Lorenza Böttner (1959-94) had an accident when she was eight years old that resulted in both arms being amputated. She rejected prosthetics and left specialised education to enrol in art school, where she began working with her mouth and feet to create paintings and drawings that challenged the perception of disabled people as disempowered and desexualised humans.

Böttner said she became an “exhibitionist” as a result of her disability and staged hundreds of live performances in the US and Europe during her lifetime; some of them are shown in videos overlaid with sage words from the artist on radical self-acceptance. Beyond carving out a space for disabled artists, Böttner’s trajectory exemplifies the uplifting adage that art is an instrument for self-actualisation. “It isn’t enough to think of an idea or just believe in an idea, one must live it,” Böttner wrote in a statement on her artistic development. “The artist can achieve this action by creating.”

William Kiyans is one of five artists who have created new site-responsive works at the Brooklyn Bridge Park that investigate identities created by transatlantic networks Photo: William Jess Laird

Black Atlantic, Brooklyn Bridge Park, Brooklyn, until 27 November

Sited along the waterfront in Brooklyn, this Public Art Fund show, co-curated by the artist Hugh Hayden, takes as its starting point the 1995 book of the same name that emphasised the hybrid identities and cultural practices created by transatlantic networks. Hayden, and Leilah Babirye, Dozie Kanu, Tau Lewis and Kiyan Williams, have created works responding to those diasporic experiences and to the site, within a harbour that was a hub for the transatlantic trade in sugar, cotton and slaves. Williams references this history directly in Ruins of Empire, an earthen statue designed to transform over the course of the show. Its form is based on a statue in Washington, DC that depicts the allegorical figure of freedom—though it was created in part through the labour of enslaved people. Williams’s re-imagined take on the figure underlines the many shortcomings of that symbolism.

Guadalupe Maravilla’s Disease Thrower #0 (2022) at Brooklyn Museum Courtesy of the artist and P·P·O·W, New York. © Guadalupe Maravilla. Photo: Stan Narten

Guadalupe Maravilla: Tierra Blanca Joven, Brooklyn Museum, until 18 September

The Salvadoran-American artist Guadalupe Maravilla describes the sculptures in his Disease Throwers series as “healing instruments” inspired by the sound therapy treatments he says aided his recovery from cancer. The shrine-like works are imbued with Maya mythology; they are assembled with various organic and manufactured materials and have a functional gong at the centre, forming an acoustic vessel whose vibrations are said to have curative qualities. The sculptures will be activated in a series of live sound baths, and are shown alongside new paintings by Maravilla and Maya artefacts he selected from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection, such as ceramic figurines, conch shell trumpets and other ritual objects. The title of the exhibition, which translates to “young white ash/earth”, references a fifth-century volcanic eruption in present-day El Salvador that displaced Maya communities; it also symbolises Maravilla’s own tumultuous migration to the US as a child in the 1980s and critiques the ongoing displacement of migrants across the US.

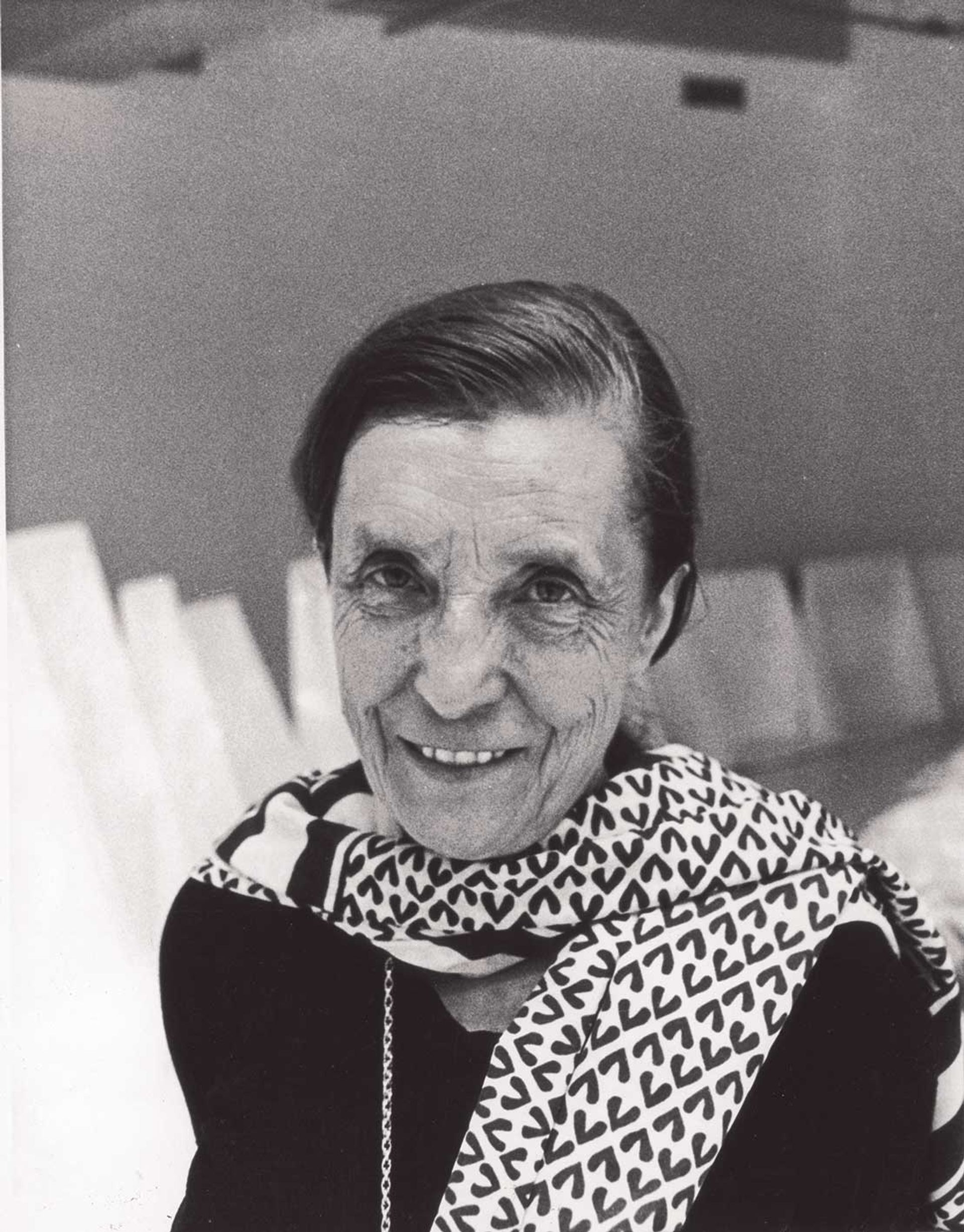

The French-born artist with her Confrontation installation in 1978 Photo: Fred W. McDarrah/MUUS Collection via Getty Images

Louise Bourgeois: Paintings, Metropolitan Museum of Art, until 7 August

Though Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) is best known as a sculptor, this exhibition curated by Clare Davies, an associate curator of Modern and contemporary art at the Met, posits her early endeavours in painting as crucial to understanding all that came after. The show focuses on her output between her arrival in New York in 1938 and her wholesale rejection of painting in 1949, highlighting forms and themes—such as domestic spaces and hybrid female figures—that would take on new dimensions as her practice evolved.

The show also demonstrates to what extent Bourgeois, before she became a singular sculptor, was engaged in contemporaneous conversations about Modernist painting, from the lingering influence of Surrealism to budding approaches to abstraction. “To date, it is not widely known that Bourgeois was active as a painter in New York for ten years, a period when the city became a vital international hub amidst critical debates around painting,” says Sheena Wagstaff, the Met’s outgoing chair of Modern and contemporary art. “This exhibition reveals the foundational DNA of the artist’s development of themes that would subsequently burgeon into three dimensions and preoccupy her for the remainder of her long career.”

Rebecca Belmore’s Prototype for ishkode (fire) (2021), on show in the Whitney Biennial Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Henri Robideau

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, Whitney Museum of American Art, until 5 September

More than any biennial in the Whitney’s new building (this is the third), Quiet as It’s Kept has fundamentally remade the museum’s interior architecture. The show’s co-curators David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards, both from the Whitney, have cited the collapsed sense of time and compounding political, health and humanitarian crises of the past three years—they began work on this biennial, originally due to open last year, in the comparatively calm year of 2019—as influences not only on their selection of 63 artists and collectives, but also on the way their works are installed.

The bulk of the biennial takes place on the museum’s fifth and sixth floors, and the two could not be more distinct. The lower level is an expansive, light-filled hall without dividing walls, where bright works by Alex Da Corte, Dyani White Hawk and others shine. The sixth floor, by contrast, is almost entirely dark, consisting of a series of dimly lit and at times claustrophobic alcoves with black walls and carpeting—appropriate for taking in mournful works by the likes of Coco Fusco and Rebecca Belmore. Broadly speaking, this architectural dualism matches the tenor of the works on each floor. Colourful, playful and meditative works are generally found on the fifth floor, while the sixth houses many of the exhibition’s grimmest and headiest works.