As invading Russian troops approached Kyiv in March, Moscow artist Alexey Beliayev-Guintovt was envisioning a laser installation to celebrate the absorption of Ukraine.

“It could be either in Donbas or in Kyiv,” he explained in a Facebook Messenger call with The Art Newspaper, referring to the contested area of eastern Ukraine, where Russian president Vladimir Putin launched the ongoing invasion on 24 February. “There could be huge laser projections, movement of quadrocopters in the black spring sky of Eurasia". Central to his installation will be “a kind of glowing dot, a sphere from which a countless number of rays emanates, each of them directed towards infinity”, he says. Each ray, he adds, will be connected to a specific message, such as “Glory to Eurasia” or “11 nuclear reactors in the hands of armed Nazis who have nothing to lose”—phrases comprehensible “only by the enlightened".

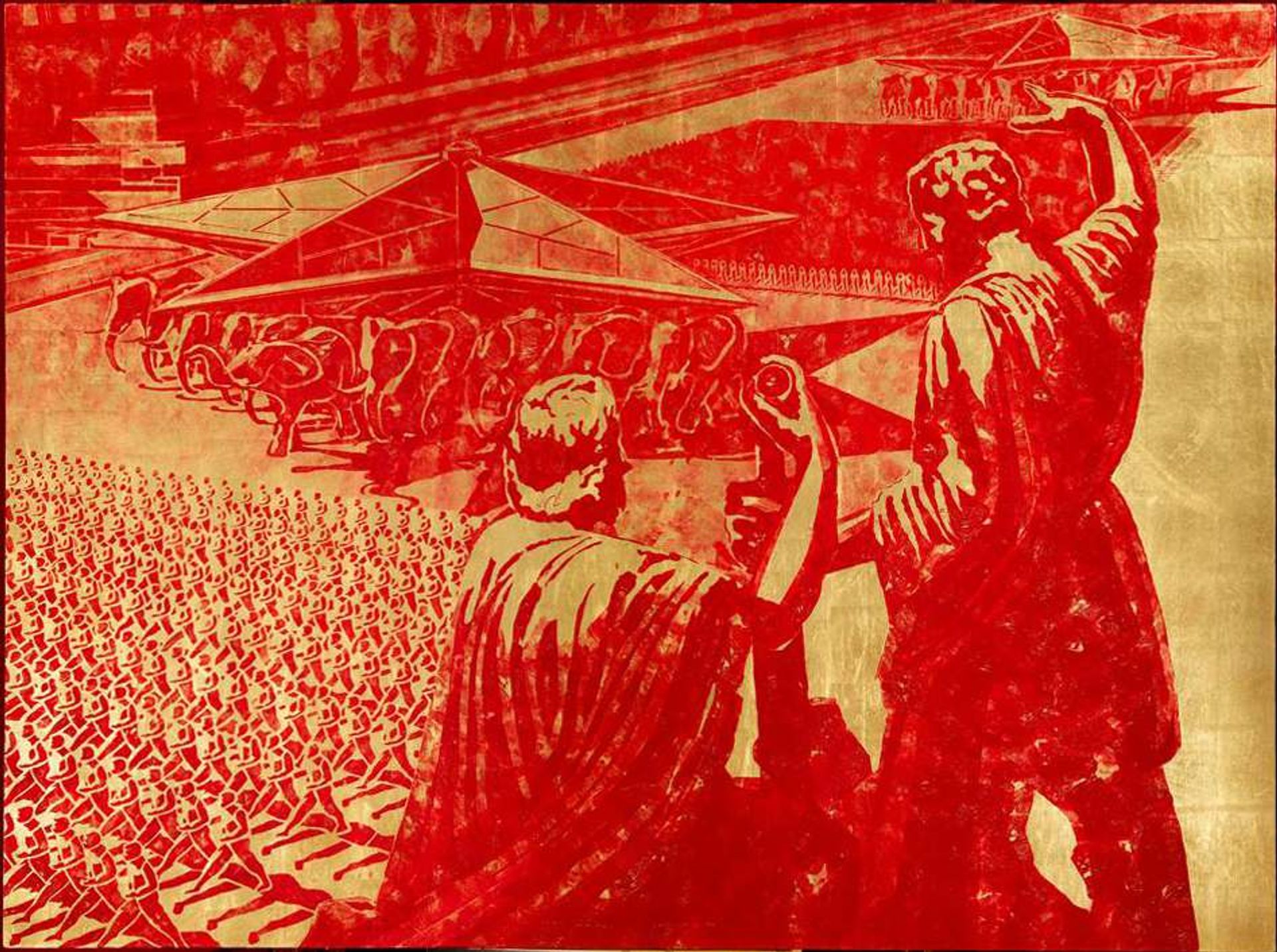

Alexey Beliayev-Guintovt's Victory Parade (2010)

Beliayev-Guintovt, like the Kremlin, refers to almost everything Ukrainian as “Nazi”, and Ukraine as “occupied territory” that must be purged and cleansed by Russia. He believes that Putin's invasion of Ukraine “will free it from nationalist dictatorship” and that the borders currently separating the former Soviet Union states will come down as they, along with other countries, are united by “the great future of great Eurasia”. He recently hosted Kémi Séba, a French-Beninese anticolonial activist who has voiced his support of Putin.

A tall, dramatic figure, the 56-year-old artist is a leader of the quasi-mystical, geopolitical International Eurasian Movement, which promotes an imperial, messianic vision of Russia straddling East and West, and is an ally of its founder Aleksandr Dugin, an eccentric philosopher reputed to have influenced Putin’s policies.

The artist says he has visited the Donbas region multiple times. “I was there during the [2014] uprising [when pro-Russian separatists declared independence from Ukraine]. I was present in the fullness of this incredible event. I was a participant. I know almost all of the heroes of Donbas. Most have already died defending their homeland and freedom. But new heroes have appeared. And we see the project developing before our eyes.”

At the same time, Beliayev-Guintovt is one of the best-known and commercially successful contemporary artists in Russia. His works feature in interior design photo shoots, have been promoted by Moscow’s Triumph Gallery and Krokin Gallery, and sell at galleries and auctions, where they attract both oligarchs and government officials, although he professes zero interest in money.

A graduate of the Moscow School of Architecture, Beliayev-Guintovt has created a signature retro-futurist style, based on Moscow’s urban landscape, which merges Soviet and Russian Orthodox imagery. His trademark painting of a Soviet red star with black shadowing set against an iconographic gold background was given a starting price of €5,000 at Moscow’s Vladey auction house in 2021; only works by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov and Oleg Kulik were offered at higher prices in the sale. Vladimir Ovcharenko, the owner of Vladey, says the auction house will not support Beliayev-Guintovt any longer.

Russia’s contemporary art scene was shaken when Beliayev-Guintovt won the prestigious €40,000 Kandinsky Prize in 2008. A campaign to strip him of the prize failed, but the fascist label has stuck to his views and work. The prize, he readily admits, was “a watershed moment” that brought him “fame in Russia and new foreign contacts”.

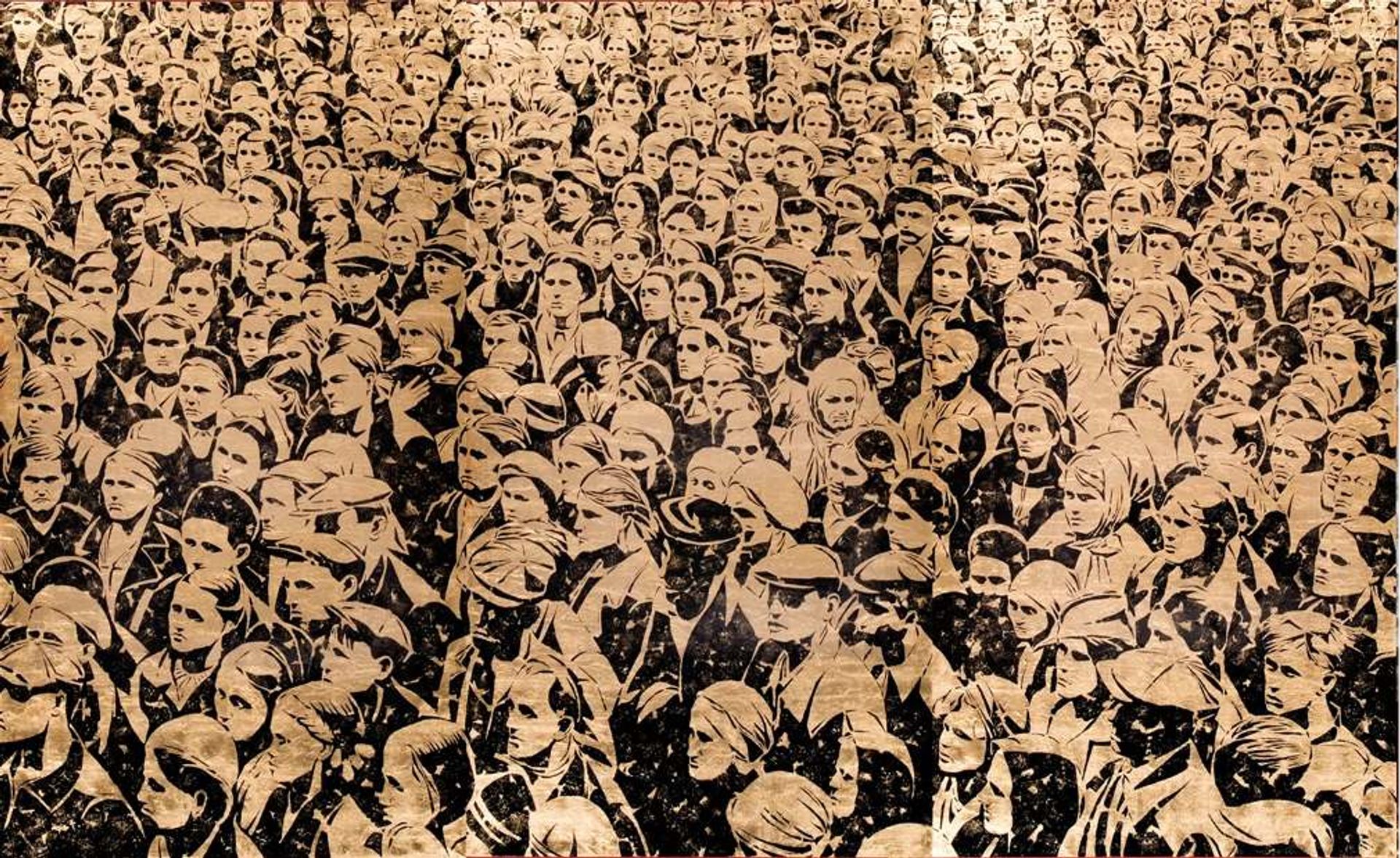

Alexey Beliayev-Guintovt's Brothers and Sisters (2008)

One of the paintings in his prize-winning Motherland-Daughter series was called Brothers and Sisters. “It shows 318 countenances of Soviet people listening to Stalin’s speech on July 6 1941,” the artist says. “This was Stalin’s first speech [of the war], and the great drama of the already ongoing and approaching overwhelming war is reflected on their faces. The very fact of the appearance of such a painting in the liberal milieu turned out to be intolerable for it."

“Yes, indeed, I was attacked by Ukrainian Nazis. There were threats, including to my life, from Baltic Nazis. It is not at all surprising that their Moscow associates—likely in their self-consciousness descendants of the losing side—were outraged by the sight of the future victors.”

Beliayev-Guintovt considers the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 a “catastrophe” that spawned at least 100,000 "unneeded artists", but believes the situation is “changing irreversibly” and that “they will become the cadres of the new figurativism”.

Happy that Russia’s Western-style art market now lies in tatters and contemporary artists are fleeing, he declares: “If someone says ‘I am a liberal,’ we hear the self-recognition—and possibly self-incrimination—that they are a fascist.”

He compares the dominance of the Russian art scene by contemporary artists to Nazi occupation, and says of the post-invasion exodus: “They have been rejected by the country, by the times, by the continent, by the winds of Eurasia, the moon and sun of Eurasia. The totalitarian sect of the destructive type is leaving us. We are starting to understand ourselves. No one is threatening us any longer. The dictatorship of liberal thought has dissipated like the morning fog. The sun of Eurasia has risen above us. It is the perfect time to review everything. What do we have? We have everything: the Russian landscape, plus a great goal.”

Russia, he believes, is simultaneously expanding and isolating. “It is an autarky of great expanse, which is growing before our eyes, showing along with the Soviet experience that our country is neither West nor East. There is a completely separate, autonomous civilisation, Russian and Eurasian. That is why everything is very, very different here.”

Alexey Beliayev-Guintovt's Star (2017)

Beliayev-Guintovt says he finds it “strange” to be asked about the art market since he is not part of it “in the traditional sense”, does not care about its existence, and simply uses it as a place to express himself. He allows free downloads of high-resolution images from his site, called Doctrine, since he does not believe in copyright.

Recalling his life as an artist in the Soviet Union, he says: “In the beginning of my creative life, I knew that no one would see what I do. I came to terms with this and focused on questions of worldview, on questions of figurative culture. When some semblance of what is known in the West as an art market appeared in our vast homeland, I, like it or not, ended up interacting with it. But the key idea is that the fact of its existence or absence is not critical to me.”

He says he undertakes projects for the state’s atomic energy, defence and culture ministries that allow him to realise his creative ambitions. “I don’t work for a ministry, I work for great Russia, for great Eurasia. If my state of being coincides with those in the ministries and agencies who are working for them as well, I am infinitely glad of this circumstance."

In the aftermath of the Bucha massacre near Kyiv, which he blames on Ukrainian forces rather than the Russian troops who committed the atrocities, he wrote in a Facebook post: “The murder of civilians in Bucha is not the first, not the second, and not the third, and, alas, not the most sacrificial crime of the agonising Kyivan regime. It is necessary to erase all traces of it from the face of our earth. Never again.”