Filipinos head to the polls today to elect their next president, and the leading candidate according to recent surveys is a controversial figure: Ferdinand Marcos Jr, the son of the ousted former dictator Ferdinand Marcos and his wife, Imelda. Among the concerns raised by human rights groups at the prospect of Marcos Jr winning the election is what will happen to the legal efforts to recover the more than $10bn his family is suspected to have siphoned out of the country to fund their luxurious lifestyle, which included secret Swiss bank accounts, real estate in Manhattan, millions of dollars in rare jewels and hundreds of works of art, many of which remain missing.

Known as Bongbong, Marcos Jr has spent his political career rewriting his family’s history, downplaying the human rights abuses committed during his father’s reign of martial law and painting that period as a “golden age” of prosperity and order in the Philippines. Marcos Jr’s recent rise in power and popularity has been attributed to a campaign of misinformation and social media blitz attacks. One particularly outrageous falsehood that has proliferated is that the Marcos family’s unaccountable wealth stems from a legendary stash of gold, which was either hidden by a Japanese general on the islands during the Second World War and found by the elder Marcos, or given to him as a gift for legal services rendered to a mythical royal family.

“The Marcoses have always been incredibly adept at using political fictions for personal gain”Pio Abad, artist

In reality, the Marcos family has been charged with large-scale corruption and embezzlement, and soon after Ferdinand Sr was deposed in the People Power Revolution of 1986, an agency known as the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG) was created to track down the family’s illicit assets. Around $5bn has been recovered by the PCGG, its chairman John Agbayani told Reuters, but another $2.5bn is tied up in court cases, and more remains missing. Imelda Marcos was convicted of seven counts of graft in 2018 and sentenced to 42 years in prison, although she is appealing that ruling.

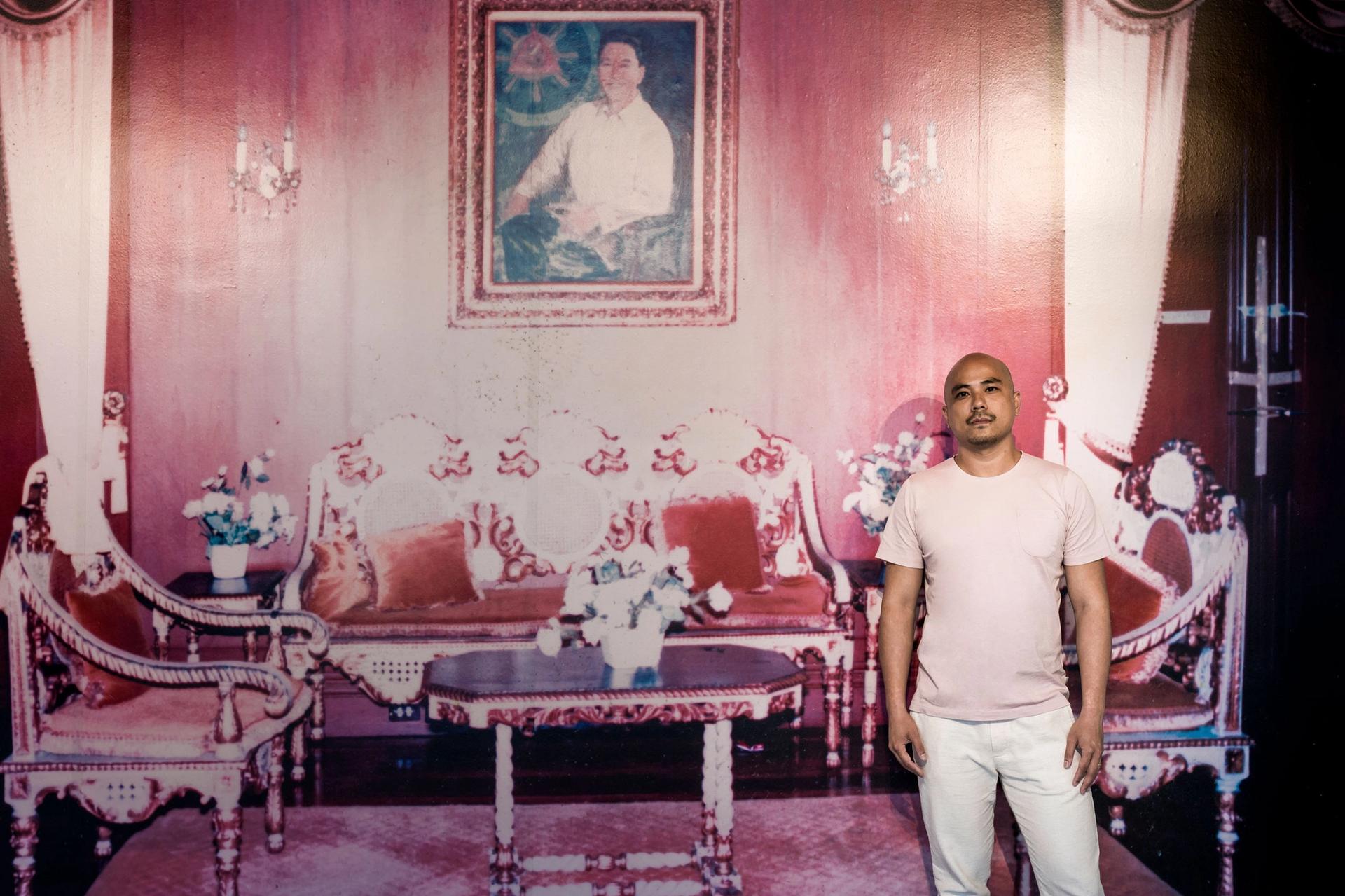

The Manila-born, London-based artist Pio Abad pictured at his exhibition Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts at the Ateneo Art Gallery in Quezon City Courtesy of the artist

“The PCGG, a presidential commission, was established specifically to find the Marcoses’ ill-gotten assets and to liquidate it on behalf of the Philippine treasury. There is still Marcos loot in the custody of the PCGG, including Imelda’s horde of jewellery,” says Pio Abad, a Manila-born, London-based artist who uses his art to expose the family’s history of exploitation. “What will happen when a Marcos is in charge of a commission tasked with prosecuting the Marcos family for their crimes? It’s not hard to guess.”

Abad is currently showing a series of works that examine the corruption of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos in the solo show Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts at the Ateneo Art Gallery in Quezon City (until 30 July). The museum is on the campus of Ateneo de Manila University, where Abad’s parents were held under campus arrest in 1980 for their political activism against the Marcos regime, after being released from incarceration in a military camp.

The show opens with a photograph taken by the artist’s mother, Dina, at the presidential residence Malacañang Palace. Abad’s parents were among the first wave of protesters to enter the Marcoses’ lavish home hours after the family was chased out of the country on 25 February 1986. In the photograph, Abad’s father, Butch poses next to a portrait of Ferdinand Marcos depicted as Malakas, the first man in Philippine mythology. Imelda was often presented as Maganda, his female counterpart.

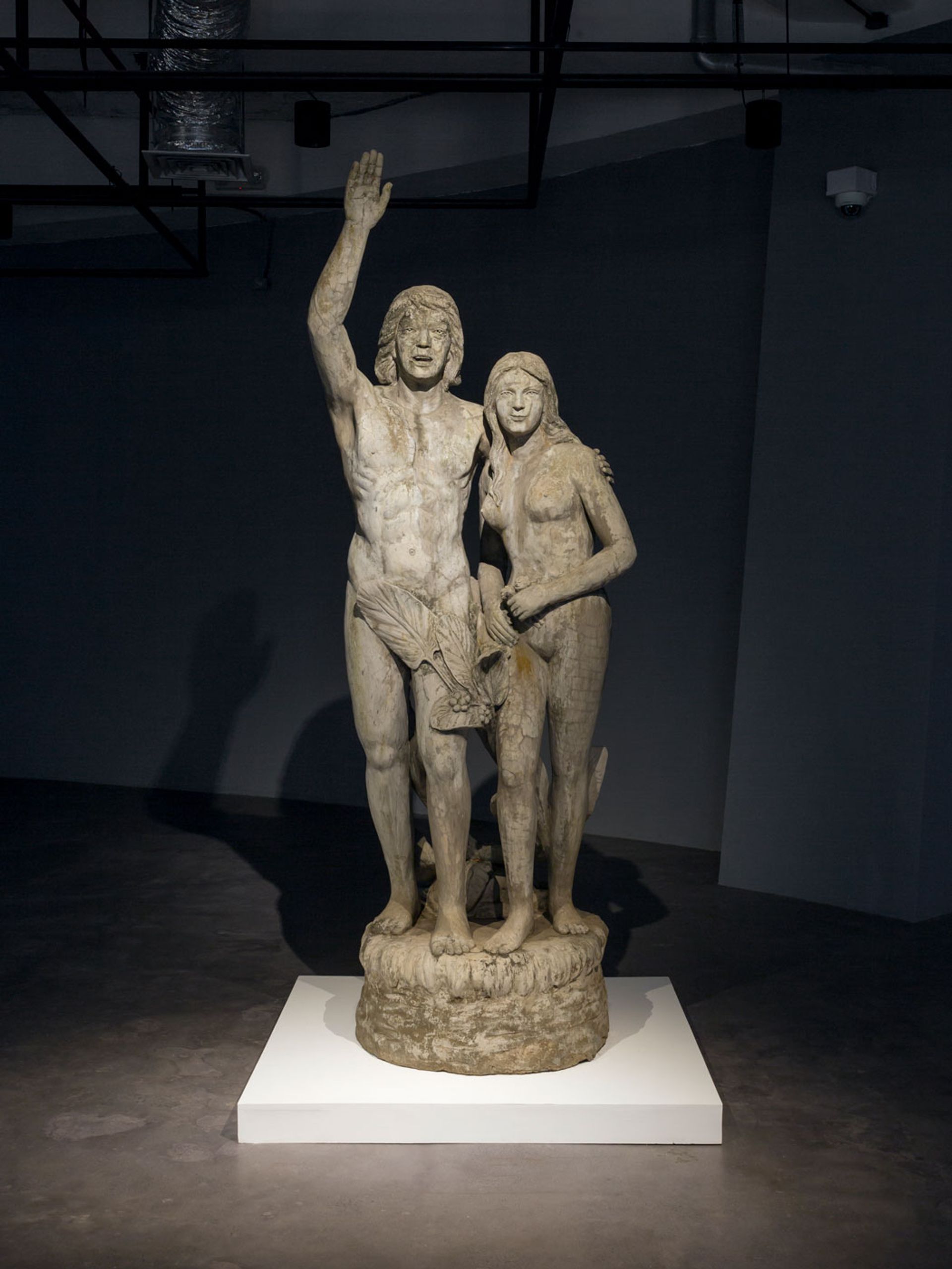

“The Marcoses have always been incredibly adept at using political fictions for personal gain,” Abad says. “At the height of the dictatorial delusion, Ferdinand and Imelda depicted themselves as the Adam and Eve of Philippine mythology, emerging naked from a single stalk of bamboo.” The propaganda machine has only become more technologically sophisticated since the family returned from a short exile in Hawaii to reintegrate themselves into the political world of the Philippines.

Pio Abad's Malakas at Maganda (1986-2022) (2014-22), an enlarged replica of a sculpture by Anastacio Caedo Courtesy of the artist; Photo: At Maculangan

“The weaponisation of social media and the rise of fake news that has empowered Trump, Putin, Duterte and other authoritarian regimes, has also been the perfect vehicle for the Marcoses to propagate further lies and misinformation,” Abad says. “They have used troll farms to attack and harass their enemies and have deployed Tiktok, Facebook and Youtube to rewrite history and depict the dictatorship as a golden age in the Philippines. And all this using the money they stole from the Filipino people.”

Perhaps the clearest demonstration of how the Marcos family robbed the country of resources is shown through Abad’s The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders, a series of works recreating the jewellery smuggled out of the country by Imelda Marcos. The title is based on the false names the couple used to open bank accounts with Credit Suisse in Zurich, where they funnelled millions of dollars for their own use.

Working in collaboration with his wife, Frances Wadsworth Jones, who is a jeweller, Abad has made 3D replicas of the former first lady’s stash of gems, which have been confiscated by the government and are kept in a bank vault in Manila. The copies are based on photographs taken of the collection when it was appraised by Christie’s in 2016, in preparation to be sold at auction—although that sale never went ahead.

Works from The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders (2019) by Frances Wadsworth Jones and Pio Abad, with Jillian Robredo, the daughter of the opposition leader Leni Robredo, in the background Photo: Clefvan Pornela

The trove of lavish jewellery has been valued at more than $21m, and with his recreations, Abad highlights the social services and public uses the gems could have paid for. A Cartier tiara, for example, could fund the treatment of 12,051 tuberculosis patients to full recovery, while a heart-shaped ruby cabochon and matching necklace, bracelet and earring set could pay for 52,631 textbooks for students in grade 11 and 12. Imelda has fought repeatedly in court to reclaim the jewels but has so far been unsuccessful.

“The depiction of Imelda Marcos as a ridiculously extravagant figure has also served as an elaborate distraction to their crimes, because it served as an entertaining smokescreen for the human rights violations, the state sponsored killings and the large scale plunder that occurred during the Marcos kleptocracy,” Abad says. He adds: “the term ‘crony capitalism’ was coined specifically to describe the Philippine economy during the Marcos regime.”

Since the family was allowed to return to the Philippines in 1991, after Ferdinand Sr’s death, they have been rebuilding their hold on power. Imelda Marcos has run twice for the presidency, unsuccessfully, but has served in the House of Representatives for three terms. Daughter Imee Marcos is currently a senator, and previously served as governor of the province Ilocos Norte, a stronghold for the family. Ferdinand Jr also served as a senator and governor of Ilocos Norte, before making a run for the vice presidency in 2016, which he lost to his current presidential opponent, Leni Robredo, a human rights lawyer and activist.

Judy Taguiwalo, an activist who was imprisoned during the dictatorship, examining Abad's postcard works that reassemble the Marcoses' collection of Old Master paintings Photo: Clefvan Pornela

On top of the whitewashing of history that the family has been promoting, many voters may not have clear first-hand memories of the dictatorship, since they were too young or not yet born by the time Ferdinand Sr was removed from power. “The absence of the horrors of the dictatorship in education curricula is also a contributing factor,” Abad says. “There has to be a reckoning with this history and the need to create a structure for teaching this history. We cannot proclaim that we will never forget if we don’t actively remember.”

But despite surveys pointing to Ferdinand Jr winning the election by a wide margin, Abad sees hope in the candidacy of Vice President Leni Robredo, who he says “has inspired an explosion of creativity and civic passion from many Filipinos.” The artist’s brother, Luis Abad, for example, is running to be the congressman of the island of Batanes, where their father’s family is from, on a Liberal Party ticket, the same party as Robredo.

“What is happening on the ground goes against the surveys,” the artist says. “Just this weekend, nearly a million people gathered together for Leni Robredo’s final campaign rally. The entire stretch of Ayala Avenue in downtown Manila was filled with people clad in pink (her campaign colour). This is also not an isolated event, as Robredo campaigned across the country, people have gathered in the hundreds of thousands to support her vision for decency and transparency in government, and to rally against the return of fascism in the country.”