It is the stuff of dreams for Henri Matisse fans. In this compact show, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and SMK—the National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen have embarked on a forensic investigation of Matisse’s The Red Studio, one of his greatest masterpieces. Completed in 1911, the painting depicts the interior of Matisse's purpose-built studio in the grounds of the house he moved to in the Parisian suburb of Issy-les-Molineaux a couple of years earlier. Matisse painted 11 of his own works in the studio—seven paintings, three sculptures and a ceramic plate—along with decorative objects. For the show, the two museums are reuniting the surviving works so recognisably depicted by Matisse in the picture—including three from the SMK’s collection—Bathers (1907), Le Luxe (II) (1907-08) and Nude with White Scarf (1909)—with The Red Studio itself.

The items are united by the colour that lends the painting its name—although it only formally gained that title when it entered the MoMA collection in 1949. “At a late stage in the process,” Ann Temkin, the exhibition’s curator at MoMA, says, “Matisse made the decision to paint over the walls and the floor—and, in fact, the furniture—with this Venetian red.” It has long been known that the red came late in the process, covering a more conventional original painting. “If you really look at the painting up close, you can see the vestiges of this initial painting underneath the red,” Temkin says. But, she adds, one of the “exciting findings” from conservators’ studies of The Red Studio “was that by looking at cross sections of the paint we learned that the painting underneath what we see today was thoroughly dry before the red was applied. In other words, there's absolutely no interaction between the painting as it was first done, and that red layer. And our conservators tell us that for that to be true—and any painter would be able to tell us, as well—that the first composition needed weeks to dry before that red came along. So, there was a period at which this painting was complete, but incomplete.” Why Matisse opted for the red has been much discussed. One theory suggests it was an optical afterimage from having been in a sunlit green garden before entering the studio. But, Temkin says, “it's more complex than any one particular epiphany or moment could account for. And Matisse himself never gave any explanation for it.”

The painting was commissioned by the Russian Sergei Shchukin—Matisse’s “greatest patron”, Temkin says. “It was part of a commission for a trio of paintings that you could be on any subject that Matisse chose. The commission was for a specific room in [Shchukin’s] mansion that had three walls. It wasn't a particularly distinguished room, it was like an entrance hallway.” The painting Matisse first produced for the commission was The Pink Studio (1911) “a much more naturalistic portrayal of the studio space which is a slightly different but overlapping area to that depicted in The Red Studio”, Temkin explains. It hangs in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow today, along with a host of other major Matisses acquired by Shchukin.

But The Red Studio did not follow it to Russia. In an extraordinary letter, Matisse explained the work—among much else, he describes the red as a “harmonic link” with the greens in the picture, and tells Shchukin: “The painting is surprising at first sight. It is obviously new. Mme Stein [another of Matisse’s great collectors, Sarah Stein, sister-in-law of Gertrude] finds it the most musical of my paintings. I relay her opinion to you knowing that you value it.” He included a watercolour sketch of the painting with the letter. But Shchukin, despite noting that the painting “must be very interesting”, did not want it; he told Matisse he now “preferred [Matisse’s] paintings with figures”.

Was the rejection as simple as that? “There was no doubt it was a very unconventional painting for 1911—and for 2022,” Temkin says, with a laugh. But Shchukin had been a “courageous champion” of Matisse’s work, as Temkin notes. He went through with an earlier commission for

the great paintings Dance and Music (both 1910), for instance, “even when those two paintings turned out to be incredibly derided when they were shown at the Salon in Paris, where they made their debut and Shchukin saw them”, Temkin explains. “He was aware he was buying something that was sort of the laughing stock of the Salon and he still, after a bit of doubt, stuck with Matisse. So this was not an uncourageous man in terms of his collecting.” Crucial to the rejection of The Red Studio, she suggests, was that he said no without having seen the painting. “It reminds me of buying online today,” she says. “Had he seen it in person, had Matisse been able to explain what he was thinking or how he felt about it, who knows how things would have gone?”

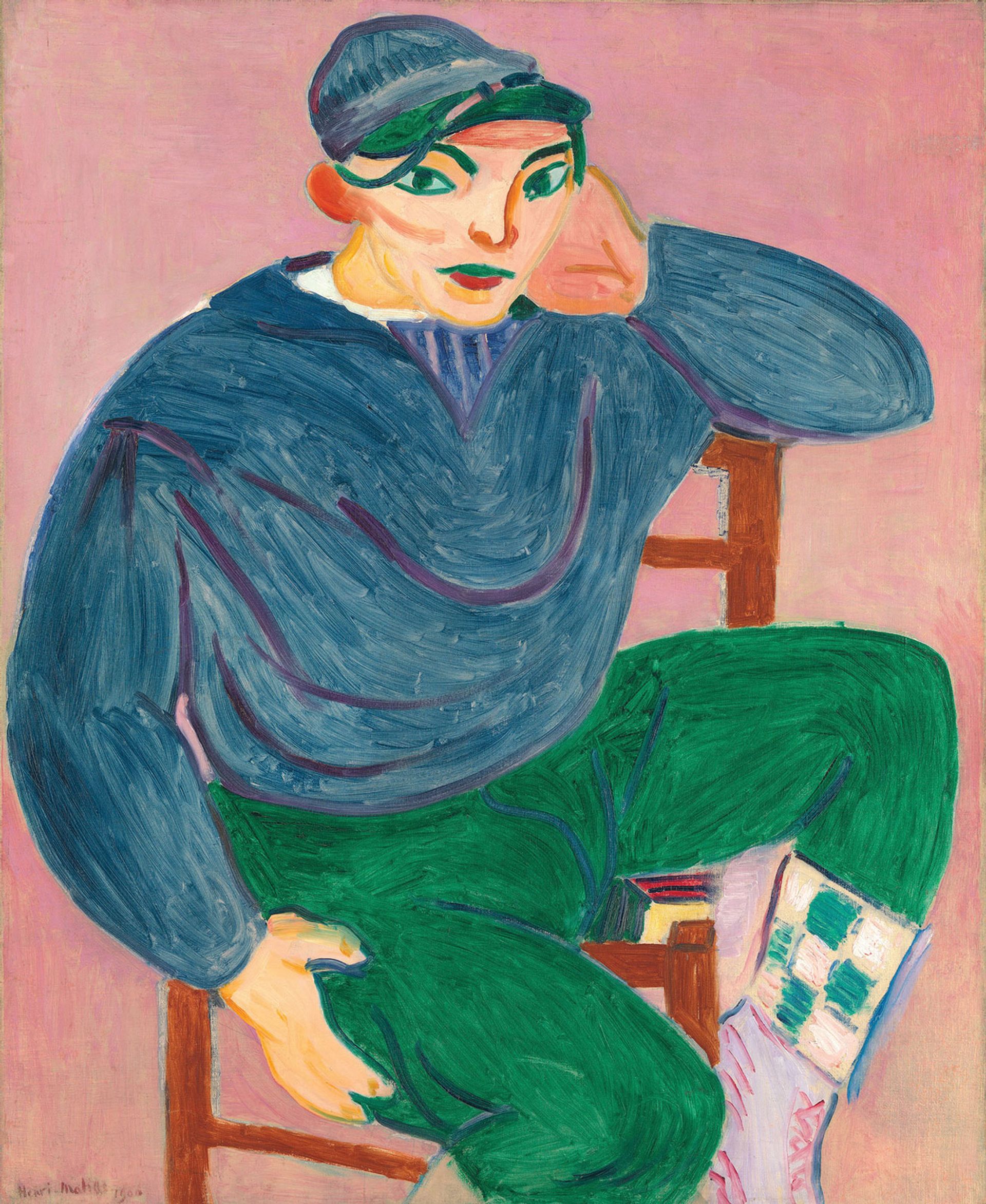

Matisse's Young Sailor II (1906) © 2022 Succession H. Matisse / ARS, New York

The rejection was ultimately to MoMA’s gain, of course. But it took 38 years to get to New York. Famously, it was in London for a long period, at the Gargoyle, a social club, and then at the Redfern Gallery on Cork Street. It remains a source of great dismay among Matisse lovers in the UK that the Tate Gallery reportedly declined to acquire it before MoMA snapped it up. Now, it is one of the greatest works at the Modern and endlessly fascinating. Temkin has clearly taken much delight in zooming in on the painting: “There is something joyful in this process that has really had to do with being able to get so close to a certain moment in an artist's work.” She adds that it is “so moving” that Matisse, given free rein by Shchukin, chose to capture his studio. “It's as if there was a part of him that knew that—at this moment, when he was still a very

controversial artist—this was the way to present a manifesto of his own artistic position at that time.”

• Matisse: the Red Studio, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1 May-10 September; SMK National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen, 13 October-26 February 2023