With his new exhibition What Goes Around Comes Around, the Mexican artist Bosco Sodi wants to make sure that Venice knows its history—and not just art history. “The world is more connected now than it’s ever been,” Sodi says. But people think this is a new idea. It is not. The world has always been connected, countries using each other and sometimes taking advantage. Discoveries in Europe influenced America, just as techniques and discoveries in Latin America heavily influenced Europe.

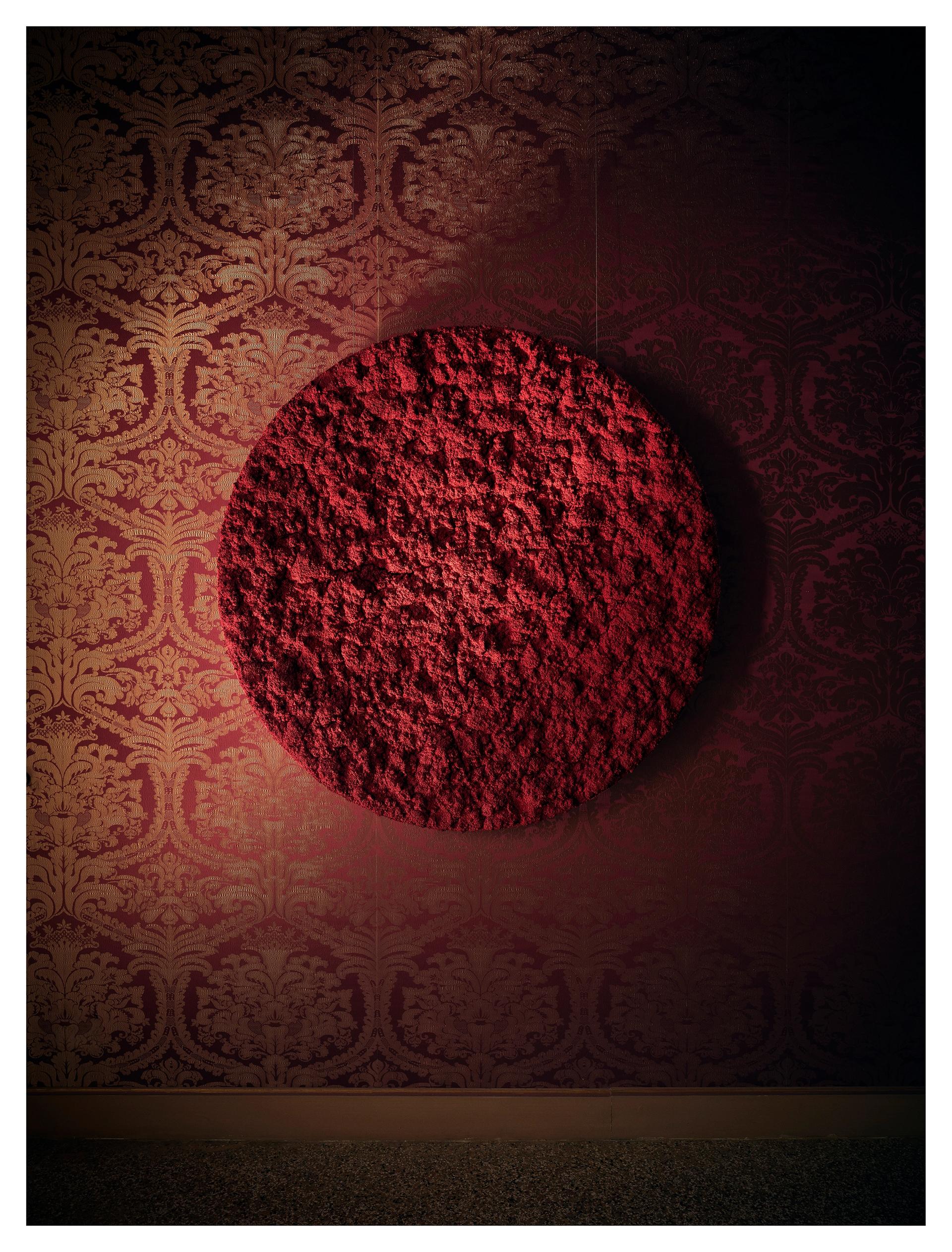

At the Palazzo Vendramin Grimani, located on the Grand Canal in the center of Venice, Sodi has inverted the historical trade routes and presented, among the marble floors and elegant walls of the palazzo, several works in his muscular, almost prehistoric style. The pieces, a combination of wood dust, cellulose pulp, glue and pigment, toe the line between painting and sculpture and bring to Venice the reminder that much of Italy’s—and Europe’s—grandeur came from the fertile soil of Mexico.

In the early-modern period, there was one color that was prized among nearly all others. Cochineal, a sultry, luminous red pigment, also known as carmine, that is derived from a species of beetle that live on prickly pear cacti, coloured the Renaissance through the colonial period. Cultivated mostly in Mexico, cochineal was one of the country’s the most lucrative exports to Europe, more so than gold and second only to silver. After Pope Paul II ordered the colour of cardinals’ robes changed from violet to red, dyes made from cochineal were embraced by the Catholic Church. The British Army’s nickname-worthy uniform tunics were also colored with dyes made from cochineal.

Palazzo Vendramin Grimani Photo by Laziz Hamani

But the colour was used for more than textiles. According to the scholar Barbara C. Anderson, “the common belief is that 16th-century tapestries of the Sala dei Duecento in Florence's Palazzo Vecchio were dyed with Mexican cochineal”, and the artist Paolo Veronese’s Four Allegories suite, which hangs in London’s National Gallery, “exemplifies the possibilities of cochineal”. The artist Diego Velázquez used the pigment in his Immaculate Conception (1618) and St. John on Patmos (1618-19), and though it has yet to be studied, scholars believe it can be found in one of his most well-known paintings, Las Meninas (1656). Rembrandt used the pigment for a glaze in The Jewish Bride (1665) and Van Dyke used it in The Balbi Children (1625-27).

"We wanted to comment on this correlation, this exchange between cultures. But it's not just about art in Europe changing completely because of cochineal. In a way we are talking about the exchange of goods. We're talking about corn. We're talking about the coffee, the cacao," Sodi says.

Sodi sees the work as a kind of revenge against the palazzo’s glossy façade and polished, genteel interiors, but he recognizes too that the work was influenced by Venice as much as it was by Oaxaca. “I’ve wanted to show here for a while,” Sodi says, “because it was a place of commerce, of cultures getting together. From Marco Polo to the Silk Road to Africa, everything connected in Venice.”

Sodi’s exhibition began with a residency in the palazzo, and he made multiple visits over several months to plan and produce the exhibition, which was curated by Daniela Ferretti and Dakin Hart. Several of the works were realized on the ground floor of the palazzo, then left exposed to the humid Venetian air before being moved to the first floor for the exhibition.

“To really understand a city takes time,” Sodi says. “Now after coming to Venice so many times, I have really begun to connect. And when you walk around Venice, you realize it is a place of texture. It’s beautiful inside the palazzos but outside all the walls are in ruins. There are many similarities to my work. Both are affected by the passing of time, accidents and our lack of control.”

195 Spheres at Palazzo Vendramin Grimani Photo by Laziz Hamani

Much of Sodi’s work revolves around the elements of time and the influence of environmental factors. Apart from the pigment works, he is also showing 195 small clay spheres, each made by hand from the soil in Oaxaca and baked in a makeshift oven on a Mexican beach. To further embrace the thematic randomness in his work, each visitor will be allowed to move one of the spheres. And when the exhibition ends on 27 November, visitors will be able to take one sphere home with them, continuing the cycle of influence and exchange that began so long ago.

Sodi will continue his work within and around the idea of cultural influence and exchange with a new not-for-profit museum in Monticello, New York named Assembly, which opens on 21 May. With the art space, once a Buick dealership in the centre of a culturally deserted town, Sodi hopes to bring an element of education. Its inaugural exhibition will, like What Goes Around Comes Around, highlight work that centers around cultural and economic change.

- Bosco Sodi: What Goes Around Comes Around, Palazzo Vendramin Grimani, Venice until 27 November.