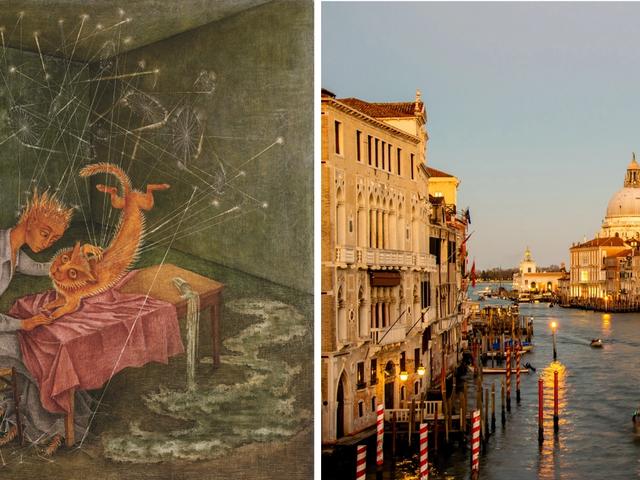

From the moment Cecilia Alemani announced the artist list for the Venice Biennale, the dominance of women was a talking point. Exclamations of excitement filled The Art Newspaper’s freelance writers’ WhatsApp group as artists such as Christina Quarles and Paula Rego were confirmed among the around 90%-female selection.

Yet immediately, mutterings of discontent seeped from the art-world woodwork. A major gallerist opined to me that Alemani’s Biennale was “politically correct”, a phrase that—like the more recent “virtue-signalling” and “woke”—is the refuge for those who see their prejudices challenged. On an opening day tour, I overheard a journalist probing Alemani in exasperated tones about the abundance of women.

Alemani responded calmly, with words similar to those she used when I asked about the show’s gender balance on The Week in Art podcast in February. The selection “came fluidly and naturally” she told me. “I’ve always worked with lots of women artists. When I wanted to invite a man, I invited him.” It was, of course, deliberately a woman-orientated list, partly because Alemani’s themes are informed by writers including Ursula Le Guin and Donna Haraway. But also, as Alemani said, “for the first 100 years of this prestigious institution, the percentage of women artists in the show was less than 10%, and in the last 20 years, it was around 30%”.

Wonder women: curator Cecilia Alemani on what we can expect at the female-dominated Venice Biennale this year

And yet it’s Alemani’s Biennale that is described by the Financial Times critic Jackie Wullschläger as “absurdly gender-unbalanced”. Even worse, despite praising artists including Rego, Precious Okoyomon and Simone Leigh, she goes on to write: “By choosing almost exclusively women, Alemani has paid a severe price in terms of quality, a cost obvious too in the contrast with many superb exhibitions by male artists across town.”

It’s one thing to decry the “academic character” of work in the show, its “stiffness” and “curious lack of sensuality”, as she does (though I couldn’t disagree more). What is absurd is to suggest that any perceived lack of quality is due to the artists’ gender rather than because of the work itself.

But then, to many of us who were in Venice for the opening week, it was unmistakable that any celebration of female creativity in The Milk of Dreams had jarringly raucous competition from male artists in august Venetian institutions. Not just in the shows themselves—including Anish Kapoor at the Accademia and Anselm Kiefer at the Doge’s Palace—but in the promotion, emblazoned across the venues, on ubiquitous posters and, most bombastically, on towering ad hoardings over churches undergoing restoration.

It’s a reminder, if one was needed, of the systemic dominance of men in art, and confirms just how vital progressive and corrective projects like Alemani’s excellent Biennale are.