In the surge of interest in 17th-century women artists over recent years, one name has remained absent: that of Caterina Angela Pierozzi. In her lifetime she was a celebrated artist, the second of only two women (the first being Artemisia Gentileschi) to be admitted into the Accademia del Disegno in Florence, and she was patronised by the Medici court—the ultimate stamp of approval. And yet, perhaps even more than the other women artists of her era, Pierozzi seemed fated to be lost from history. For centuries, not a single work of hers was thought to survive.

But all this changed in late 2020, when a small work was discovered in France that could be confidently attributed to Pierozzi (it is even signed and dated). Today, that painting goes on show at Colnaghi Gallery in London as part of the exhibition, Forbidden Fruit: Female Still Life, with a six-figure price tag.

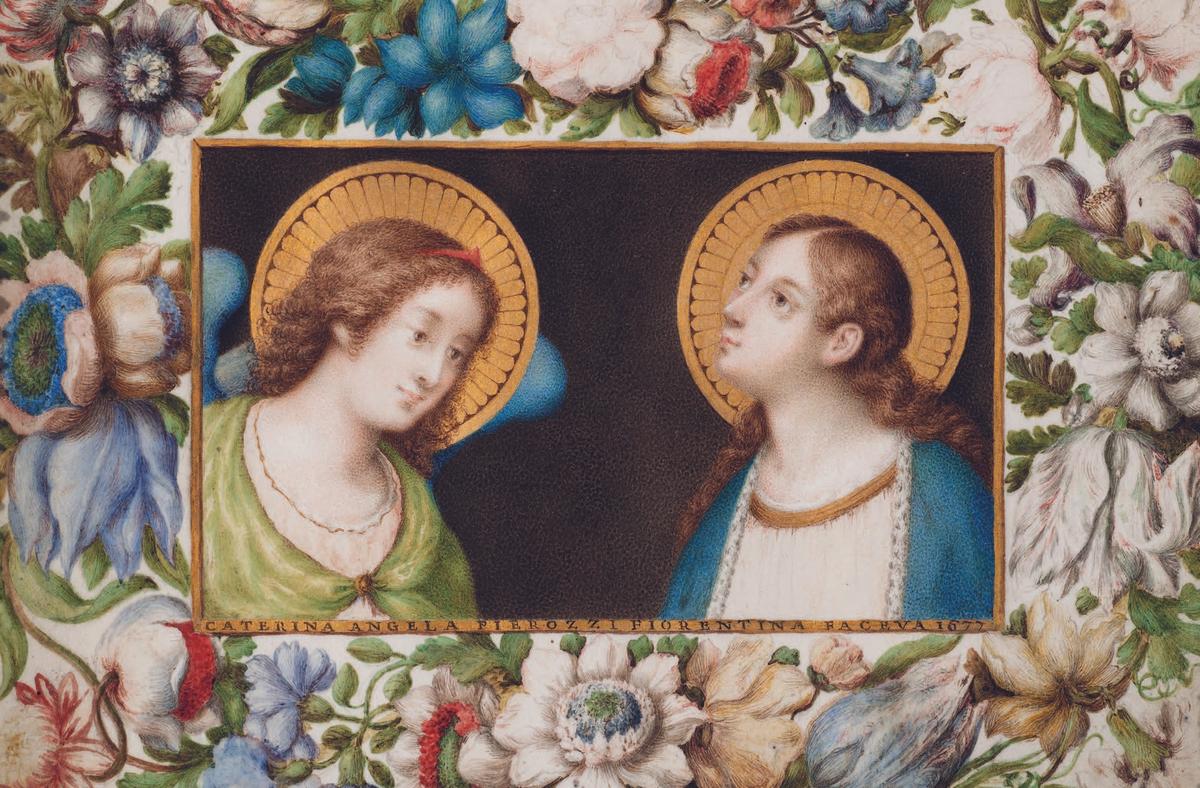

This intricate painting measures scarcely 15cm by 20cm, which is in keeping the skills she was celebrated for. The connoisseur and keeper of the Medici art collection, Fillipo Baldinucci, praised her as a miniaturist, applauding her compositions as being so full of naturalness and beauty that "no more could be desired”.

These are the qualities present in the newly found work. It is a miniature, a scaled down copy of a 14th-century Annunciation fresco, which was prized by the Medici court and copied for them many times over. The curled tendrils of the Madonna’s hair show why Pierozzi had such a reputation for intricacy: they rest gently on the Madonna’s shoulder, as she casts her eyes up to heaven in devotion. The angel Gabriel mirrors her gaze downwards, his expression one of sacred serenity. But beautiful though these central figures are, it is to the border that the eye is drawn. Coiling and twisting flowers cascade and bloom. In contrast to the stillness of the central figures, they almost seem to move and sway. If you look closely, you can see every line that Pierozzi has drawn, demonstrating her skill in disegno, the technique favoured in 17th-century Florence.

These flowers are also exceptionally accurate—hyacinths, lilies, irises, all of which appear to have been drawn from life. Pierozzi’s focus on the floral aligns with the burgeoning interest in botany and horticulture at the Medici court, and this panel was most likely a commission from the Grand Duchess herself, Vittoria della Rovere, who was a great patron of the arts—particularly of female painters. One of her most favoured court artists was Giovanna Garzoni, whose work will be shown alongside Pierozzi’s at the Colnaghi exhibtion.

With this momentous discovery we have the first piece of the puzzle of Pierozzi’s oeuvre, and it is thrilling to imagine what else might be out there to find.