"I want to make people with disability more visible in art," the Ukrainian artist Anna Litvinova tells The Art Newspaper over Zoom. She is speaking lying down on her bed — her condition, called myopathy, a genetic weakness in muscles, makes sitting for more than a few hours per day tiring for her. She is currently living with a host family in a Moldovan village in the Anenii Noi district, where she fled, together with her husband, who is also in a wheelchair, and her parents, on the eighth day of the Russia-Ukraine war.

"We saw that the Russian army was coming so close to our town, that we feared that we wouldn't be able to leave later. We heard the sirens everyday. It was very scary," Litvinova recalls. Fleeing from Odesa, Litvinova is one of more than 100,000 Ukrainian refugees who have found shelter in neighbouring Moldova, a small country of 2.5 million people. Like Litvinova, the vast majority of these people are staying in private homes.

"I want to contribute to creating a culture where people can accept others who are not like them"

The Ukrainian-Moldovan border is only 60km away from Odesa, so Moldova has become Odesans' main destination on their route to safety. Yet, if during peacetime, the journey would only take a couple of hours, the traffic jams and the long queues at the border meant that it took Litvinova 20 hours to make it to Moldova, where she had to wait in the line of cars for seven hours. It was 2AM when a volunteer approached Litvinova and her family, and took them to his home, 150km away. They have stayed with his family for more than a month now. "They have been extremely kind," Litvinova says. "They have even bought me a bed which changes heights, from a relative working at the hospital. [Without such a bed,] I can't sit or get up without assistance. This bed allows me to move on my own. I didn't even dream that I could have a bed like that outside my home," she adds.

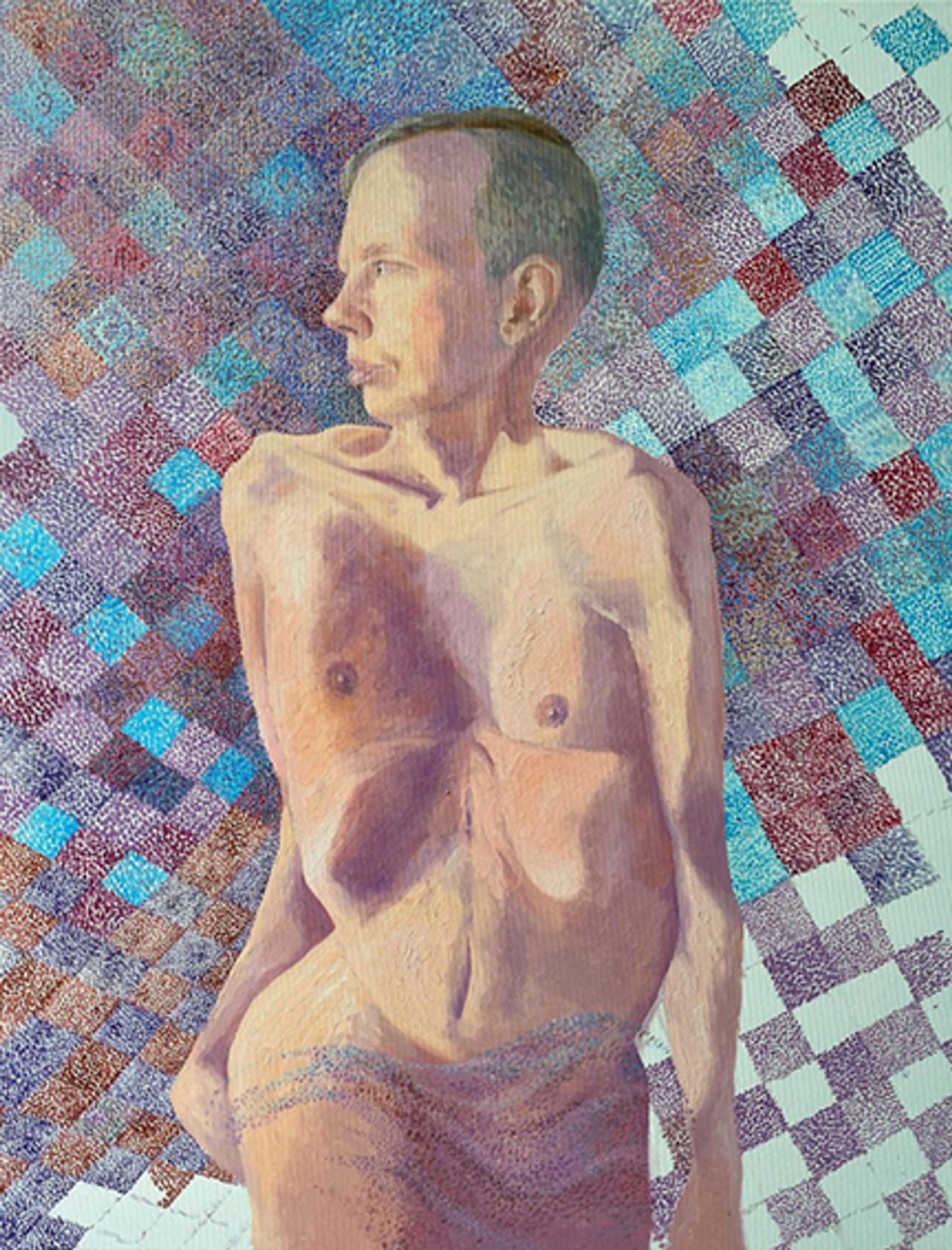

Anna Litvinova, The Edge of Sexuality (2021) © Anna Litvinova

Litvinova used to make more traditional landscape and portrait painting but for the past two years, she has focused on depicting disability in her work. "Choosing to speak about disability has been very therapeutic for me," she says. "It helped me stop being fearful and ashamed of my body." Her new artistic direction came following two years of therapy to treat depression, which she describes as "an important step" in her life. "I want to contribute to creating a culture where people can accept others who are not like them," she explains. In her pursuit of visibility, Litvinova cites two artistic influences on her: the Young British Artist Jenny Saville, for her large-scale realist female nudes, and the New York-based Jennifer Packer, for her commitment to black representation in art.

With shades of pink, blue, and grey, and often using pointillism, Litvinova's figurative oil paintings are tender depictions of her own body and her husband's body. Wanting to take the same mission into the realm of photography, yet physically unable to work with a camera herself, Litvinova searched for a photographer with whom she would capture her nude body. She found fellow Odesan Vitaly Rushinksi online. "I met up with him for a coffee and we discussed the concept of the photoshoot, making sure we were on the same page," she says. In December last year, they rented a studio. "The male gaze was important for me, because, while feminism has achieved a lot, commercial culture is still very powerful, and the pressures of an ideal body are still great," Litvinova explains. The experience was empowering for her. "When I saw the photographs, I felt proud that I did not fear the camera, that I can fight for the acceptance of my body and my illness." Next, Litvinova wants to continue the series by working with photographers on the nudes of other people with disability: her husband, friends, and others.

Anna Litvinova, The Edge of Sexuality (2021) © Anna Litvinova

Litvinova says that she decided that she wanted to become an artist at the age of ten. She asked her parents to take her to art school. Physically unable to travel to school, she received art tutors at home instead, and then went on to do an art degree at the Ukrainian University of Uman through distance learning. This is because Ukraine's infrastucture is still poorly developed to enable the access of disabled people in the public places — although, just before the war, that began to change.

Anna Litvinova, Reconstruction of beauty (2021) © Anna Litvinova

"I only started seeing people in wheelchairs on the streets of Odesa in the past two years," she admits. "The roads became better, and they added platforms on cobblestones, so that I became able to cross the road in my neighbourhood, and go to the park." Still, unable to use public transport, Litvinova says she has relied on her father's car and help picking her up the stairs whenever she needed to go into town. While the artist has had two solo shows and took part in several other collective exhibitions in Odesa, Uman, and Moscow, there was one instance she remembers where a local gallery owner refused to host her show because "the works of a disabled artist would bring a bad aura" to the place.

Litvinova fears that following the war, life for her will become even more difficult in Ukraine. This is why she is applying for a Talent visa in the UK. "I hope that in the UK, I can realise myself as an artist. I have friends who are artists there and I hope to see them but I also think that as a person with disability it will be easier for me there, given the country's more developed infrastructure."