The first picture you see in Marlene Dumas’s show at the Palazzo Grassi is tiny: 30cm by 40cm. From the bottom of the steps leading from the Palazzo’s atrium to the landing on which it hangs, it looks little more than a bloody stain across an otherwise largely blank canvas.

Get closer, and the image coalesces: a kiss, stolen, like so many other Dumas motifs, from a cinematic image (this time, Jean Renoir’s Partie de campagne, made in 1936). What sets Dumas apart from so many others who use found images is the painterly details that lift her works beyond the source material and into a painterly realm entirely her own. There, with the brush, she can not just reinterpret it, but seemingly do anything she likes, pushing the limits of absurdity, whether through extreme use of colour, the abrupt abstraction of a body part or face, or apparent bursts of pure painterly reverie. The power of Kissed (2018) is in its polarities: the deep red of the man’s face, the pale blue-lilac of the woman’s cheek—the sky, reflected in the woman’s face, we’re told in a guide with notes written and selected by Dumas with her studio manager Jolie van Leeuwen. In those same notes, Dumas reflects on the ambiguity of her image. After the first kiss, she writes, “there is always the fear of a fall”.

It is this tightrope that Dumas’ work walks. I know of no other painter who seduces and repels so starkly, even within a single picture. And it is beautifully reflected in the Grassi show, which uses the layout of the building, over two floors, to frame the show thematically. Effectively, it is two retrospective journeys, each triggered by recent bodies of work. The first floor, "Myths and Mortals", takes its cue from the pieces inspired by Shakespeare’s poem Venus and Adonis, shown at David Zwirner in New York in 2018, and the second level, "Double Takes", is informed by a series of paintings partly based on Charles Baudelaire’s prose poem the Spleen on Paris, first shown at the Zeno X gallery in Antwerp. The show’s curator, Caroline Bourgeois, writes that the paintings and ink drawings organised around the two groups of work are “in echo” to them. And these are profound reverberations. Though it is sparely hung, the works from different decades are in productive, often exhilarating conversation.

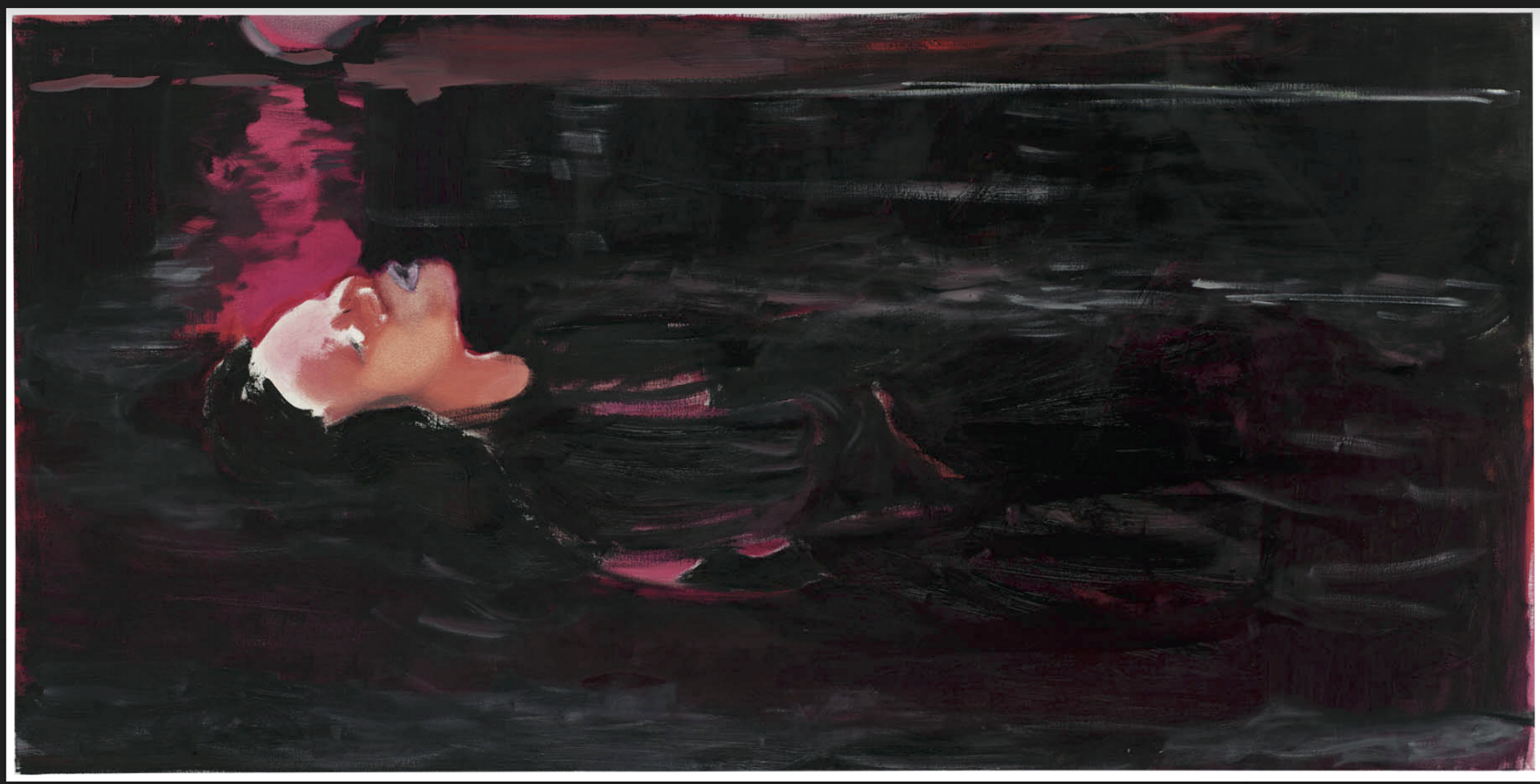

Marlene Dumas, Red Moon (2007) Photo: Peter Cox, Eindhoven © Marlene Dumas

The themes broadly mean that more erotic and bodily paintings appear on floor one, and more geopolitical and deathly images are upstairs. But these preoccupations are intimately connected across many rooms of the show. So much here is pregnant with mystery. Red Moon is a latter-day Ophelia, a woman in the blackest water illuminated from the skies, deep crimson bands on the water, her face almost glowing to a white heat. Dumas tells us that she might not be drowning, but “floating freely, at ease with her independence”. Yet she has cold, grey lips.

Time and again, moments like this stopped me in my tracks. Dumas is an endlessly daring painter, in the way she uses the paint, in what she asks her medium to do, in the scale and formats she chooses for her work, and in the way she reflects on the art of the past. Immaculate (2003) is a tiny, blurry painting of a vulva, not even a foot high, but it grapples with the theological idea of immaculate conception—where is the bodily pleasure in being born free of original sin, she seems to ask.

The Particularity of Nakedness (1987), a very early work, is a three-metre-wide painting of her then lover, and later life partner Jan Andriesse, oddly narrowing towards his feet. The painting’s visual source was a number of Polaroids joined together, but Dumas eliminates the joins. The distortions add up to an elegantly stretched figuration reminiscent of Egon Schiele. Yet there’s an undeniable tenderness amid the strangeness and intensity.

There is much to delight in here, too—even outright funny moments, like the bright purple penis of the figure in D-rection (1999) or a caricatured rat, crudely outlined and filled with a grey-green mist, a rather pathetic creature. And yet in the notes to The Rat (2020), Dumas tells us that it’s “about these times, and about Time”. You could say this about almost everything here, in the best sense. The paintings around the rodent, triggered by the Baudelaire prose poems, have a mournfulness fitting for their literary source but also for the age we’re living through. They include a portrait of Baudelaire which seems to drip with the melancholy and disgust he felt on the streets of Paris, as described in the book, but also a beautiful and tender portrayal of Hafid Bouazza, the writer and translator with whom Dumas was working on the Spleen of Paris works when he died.

Marlene Dumas, Death by Association (2002) Photo: Peter Cox, Eindhoven © Marlene Dumas

Her most political paintings—those responding to the humanitarian catastrophe of Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories—are painful and touching by turns. Death by Association (2002) depicts a dead Palestinian boy with a Qur’an on his chest with a lyrical softness. But Figure in a Landscape (2010) fills the canvas with one of the vast walls dividing communities in Israel-Palestine, beneath which walks a tiny figure. It is brutal, both in its sardonic, anti-Romantic title, and in the rawness of its application of paint. Dumas is a great painter of anger.

Throughout, the show is like a body-blow and intoxicant at once. It’s exhausting and uplifting. But the final painting, alone in a room, provides a solemn coda. Persona (2020) is based on a plaster copy of a mournful face by Auguste Rodin, one of the studies for his never-finished Gates of Hell. It is almost liquid, a beigey pink wash with the desolate face inscribed into it, in quickly-made gestures. Dumas painted it “during a period of anguish”, the notes tell us—this may refer to Andriesse’s cancer diagnosis; he died in 2021. But we barely need the confirmation. The anguish is written in the material of the painting. It looks like it was painful to make. Yet it does all it needs to do, with a quiet insistence that resonates as you leave this extraordinary show.

• Marlene Dumas: open-end, Palazzo Grassi, Venice, until 8 January