Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has inevitably prompted distressing images of the destruction of cities, and with them communities, across the country. And among those communities, of course, are artists. In the past, artists have provided remarkable and enduring records of war and its effects and the Russia-Ukraine crisis is no different. Today, artists are in Kyiv, Kharkiv and other cities under attack, and continuing to make work. But they have been on a war footing since the 2013-14 Revolution of Dignity (also called Maidan, meaning independence, after the square in Kyiv in which the protests took place), Russia’s annexation of Crimea later in 2014, and the war that has raged in the Donbass region in eastern Ukraine.

On The Week in Art podcast on 4 March we spoke to Svitlana Biedarieva, a Ukrainian art historian, artist and curator based in Mexico City, who co-organised the exhibition At the Front Line: Ukrainian Art 2013-2019, shown in Mexico in 2019 and Canada in 2020. Biedarieva is also the author of a recent book on contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic art. She told us about the strand of documentary art that has dominated Ukrainian art in recent years and how artists in Ukraine are now responding to the Russian invasion. Inevitably, this situation is fast moving and may change as the war develops.

The Art Newspaper: Have you heard from artists who are currently in Ukraine?

Svitlana Biedarieva: Yes, I am in contact with many of the artists who are now in Ukraine. And now they are in a really difficult situation. Some of the artists managed to leave the hot places like Kyiv and Kharkiv and to move towards Western Ukraine or the Polish border, but many of them are staying inside Kyiv and Kharkiv. And it’s not only because of impossibility to get out, because there is a possibility, but many of them have quite strong civil positions and they need to stay and help in any way—through volunteering, defending or even documenting all these traumatic events, and performing their duty as artists but also as documentary practitioners.

You’ve written extensively about the fact that documentary has actually become a notable form in recent Ukrainian art, as a response to the conditions of war that have existed in Ukraine over the past decade.

Yes, I have written several texts on this topic. And the idea is that Ukraine after 2013, and the protests in the Maidan and then the annexation of Crimea, and then the beginning of the war with Russia, experienced a very strong necessity to document the ongoing events. And artists took [on] this responsibility. And that’s how the documentary turn in Ukrainian art occurred. So we can speak about photography, we can speak about short films that are on the border between cinema and contemporary art, we can speak about media art, and we can speak about new genres, like, for example, reportage art that appears with the beginning of the violent events in the east

of Ukraine.

How straightforwardly documentary are they? What kind of subjects are the artists dealing with?

The Ukrainian film-maker Piotr Armianovski comes from Donbass. He needed to leave Donbass in 2014 because he was active there in the organisation of democratic elections and so he was blacklisted by the pro-Russian groups who entered the occupied part of the Donetsk region. And he continued to work from outside the area, but approaching the area from the side of Ukrainian territory. And he was filming the very process and the consequences of military actions in those towns near the demarcation line. And his work became very important precisely for this combination of a documentary approach and very personal approach, because he’s attached to this area—he knows people from this area [who can] tell their own personal stories.

Another example is the work of Yevgenia Belorusets, who is a photographer and a writer. She travelled to the border with the occupied territories, to small mining towns. She was documenting lives there and the routine that was overshadowed by these war conditions, and generally the economic and cultural conditions in which these people live. And there was a big focus on the life of women, female miners, in this project. Documentary becomes a background for something more—for a story that has to be told. And this story is not a story of one person, but of a group of people who are finding themselves in certain difficult situations. So this is a trend that I would say Ukrainian documentary art is following now. And I know that Yevgenia Belorusets is in Kyiv, and she’s trying to document the ongoing aggression of the war and the ongoing events. I still don’t know what kind of project it’s going to be because, of course, now it’s very difficult to publish anything like that, to document the destruction, for example. But these projects keep on going.

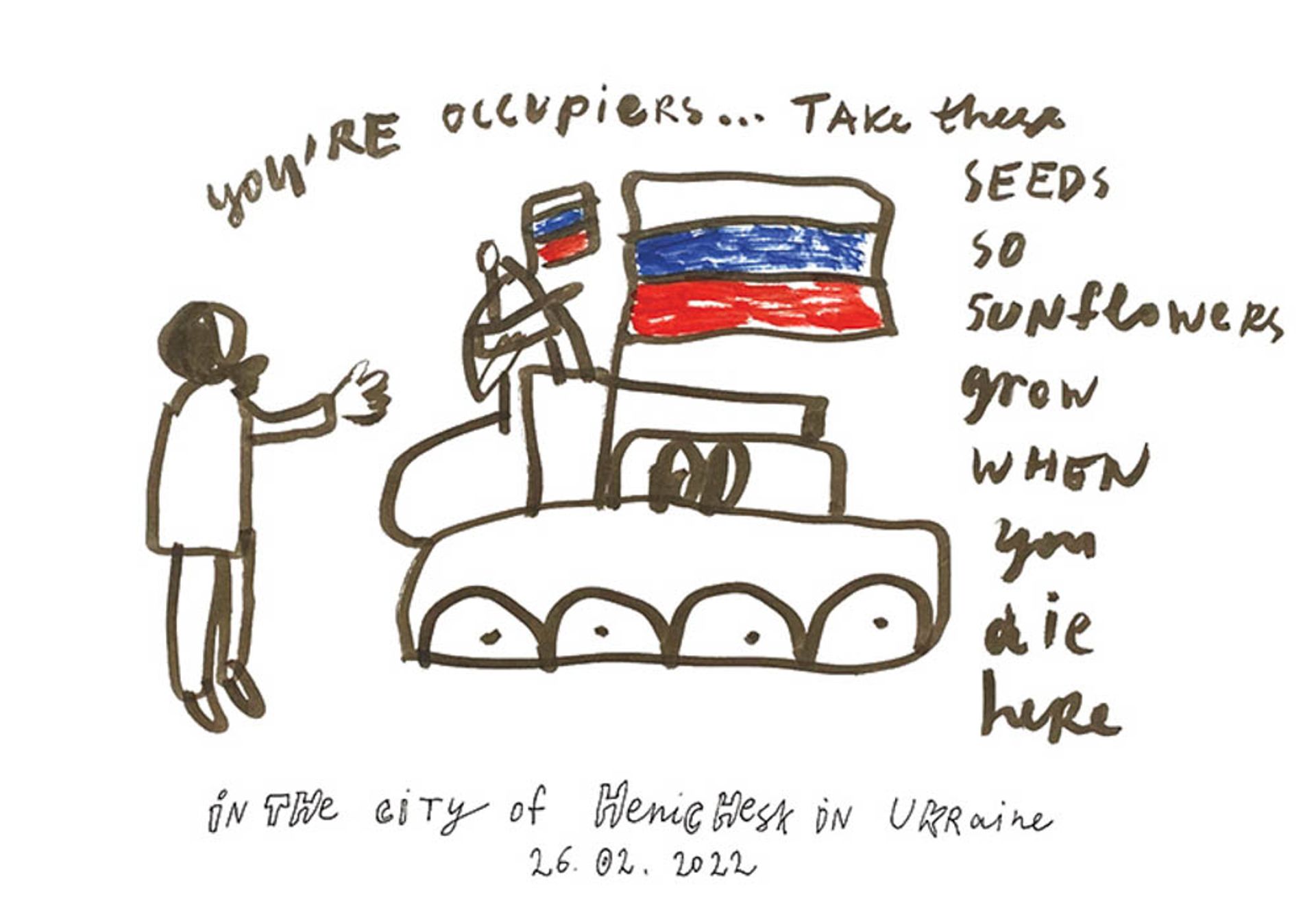

A drawing by Alevtina Kakhidze, made two days after the Russian invasion

Alevtina Kakhidze documented the life of her mother in the Donbass. Her mother needed to stay there all the time while the territory was occupied, but Alevtina couldn’t visit her. The worst part of the story is that her mother needed to travel to receive her pension from the Ukrainian government—to cross the demarcation line every month. And [eventually] she died because of these enormous queues and enormous bureaucratic, chaotic procedures needed to cross the border. Now, Alevtina also is working on several graphic projects that reflect on the current state of war, and the bombs and shellings that are occurring just next to her house, near Kyiv.

They see it as essential that they report on current events. It’s not just about reflecting the wider culture, but reflecting events as they happen. It seems extraordinarily courageous.

Yes, I agree with you. It is important that artists, even if they had to leave their homes, even if they’re displaced, have this privilege to voice the opinion of society and represent the life of the society. This is one of the big responsibilities that they can perform right now.

• Visit the websites of Svitlana Biedarieva, Piotr Armianovski and Yevgenia Belorusets. Alevtina Kakhidze’s work can be seen on Instagram: @truealevtina