Could the Dutch pavilion provide the perfect tonic after two years of virus-induced separation? The video installation by melanie bonajo, When the body says Yes, will explore the importance of touch and intimacy in a world of ever-increasing isolation. There was “already an epidemic of loneliness”, bonajo says. “But then [Covid-19] came and made the epidemic of loneliness into a pandemic.”

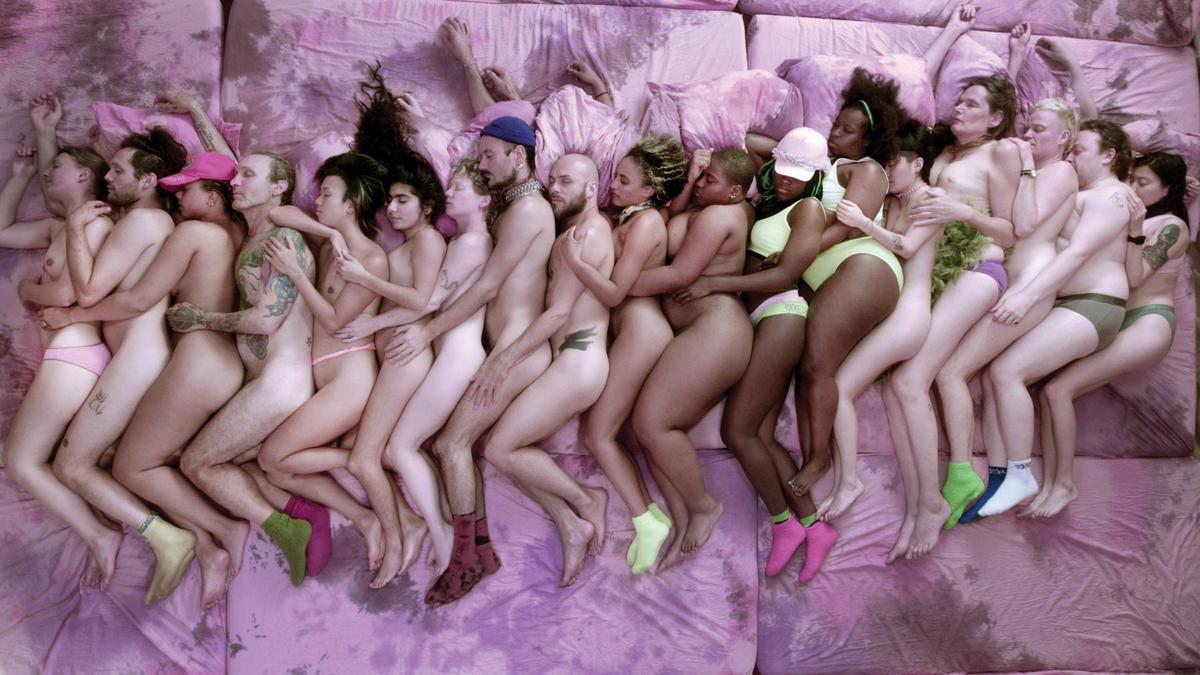

The work for the Venice Biennale was inspired by bonajo’s “training as a somatic sex coach”—where practitioners explore intimacy, consent and sexual boundaries—and it “is really an invitation, and also a celebration of the body as a vehicle of knowledge”. The artist often works with people on the periphery of society, such as sex workers or indigenous farmers, lending them a voice that might not be available to them. The visceral films take on big topics such as the climate emergency and global capitalism through playful and surreal imagery, with the often semi-naked collaborators donning colourful ensembles and face paint in scenes recalling ancient mysticism.

A still from bonajo’s film, which the artist describes as “a celebration of the body as a vehicle of knowledge” Photo: Sydney Rahimtoola; courtesy of the artist

Out of the comfort zone

The work at the Biennale will be presented in a deconsecrated 13th-century church in the Cannaregio district of the city, with the Netherlands’ Gerrit Rietveld-designed pavilion in the Giardini being lent to the Estonian delegation this year. The decision was made by Eelco van der Lingen, the pavilion commissioner and director of the Mondriaan Fund, who has said the move gives the Netherlands an “opportunity to step out of our comfort zone and see what freedom it gives us”.

The Chiesetta della Misericordia was chosen as the venue partly because many of the subjects that bonajo deals with in their work are also those traditionally “suppressed by Christianity”, says the artist, before reeling them off: “suppression of the body, suppression of the feminine, suppression of sexuality, suppression of sexual orientations beyond the heteropatriarchal family systems, the female orgasm, intimacy beyond sexuality and reproductive means…”

A portrait of bonajo: playful and surreal imagery are features of the artist’s work Photo: Joseph Marzolla

But beyond the church’s symbolic meaning, there was also the fact that it was simply “a beautiful space and I really felt that in my body,” bonajo says. “The church is already built to extend your body beyond the physical. It’s a giant space, the light comes in in a certain way, your senses are engaged with the space in a different way than if you go to the Rietveld pavilion—that’s Modernism.” Bonajo’s video will be presented in soft and tactile environment where visitors can relax and become comfortably aware of their own bodies. “We are against chairs,” bonajo says, only half-jokingly, because they represent “order and obedience—and actually [chairs are] very bad for the body”.

“Plus,” bonajo adds, “this church is also called the church of compassion, ‘misericordia’, and it has a history of trouble, of not finding its way in the church system and has been passed on to different orders and institutions. It’s like the ‘queerdo’ [a mix of queer and weirdo] of the churches.”

I have the power now to bring out a voice that is usually censored and repressedmelanie bonajo

Many of the artists participating in the Biennale will be able to relate to the anxieties that the pandemic has raised during the long planning stage. The artist cites the possibility that it might be cancelled or postponed again, of collaborators getting ill, not being able to travel, and colleagues losing loved ones. At points they even questioned the decision to take part. But bonajo says they felt a sense of responsibility towards the people they collaborate with to make work, such as the video editor, designer, body workers or social justice activists. Taking part in the Biennale “is a way for our group to be represented and heard. I have the power now to bring out a voice that is usually censored and repressed,” the artist says. “That’s the platform that Venice gives, and it also shows who has the power to make culture.” But equally, the Biennale is not the be-all and end-all of life. “It’s just a harbour,” bonajo says. “We’re on a journey and it doesn’t end in Venice.”

Netherlands

Artist: Melanie Bonajo

Organisers: Orlando Maaike Gouwenberg, Geir Haraldseth and Soraya Pol; Mondriaan Fund

Where: Chiesetta della Misericordia