Few curators anywhere in the world could be a more natural fit for the Venice Biennale than Cecilia Alemani. Born in Milan in 1977, Alemani has directed the acclaimed programme at the High Line in New York since 2011. She has met the logistical challenges of that brief with aplomb, instigating a series of presentations involving artists from across the world with progressive themes and ideas and a visually acute response to a complex space.

Alemani also has experience in Venice, curating the Italian pavilion in 2017. She has worked across numerous art world territories, from the commercial market as director of Frieze Projects in New York and curator for Art Basel Cities in Buenos Aires, to biennials, as a guest curator for the performance biennial Performa in New York, for instance, and museums, including co-founding No Soul for Sale, a festival of non-profit art organisations at Tate Modern in London. Her exhibition’s title,The Milk of Dreams, was taken from a children’s book by Leonora Carrington, which, Alemani says, “talks about a world where creatures that are hybrid and in constant metamorphosis can be transformed and become someone or something else”.

Gabriel Chaile’s large-scale sculpture Mamá Luchona (2021) is one of the contemporary works on show, alongside “capsules” of historical works © dariolasagni.com

“I wanted to use this atmosphere and this fluidity to create an exhibition that talks about metamorphosis of the body, and of the definitions of humanity,” she adds.

As Alemani announced her plans for Venice in February, she told The Art Newspaper about the long, fractured gestation of the show amid the pandemic, about the dominance of women and gender-nonconforming artists in the exhibition, and about turning to the past to set the context for the art of the present.

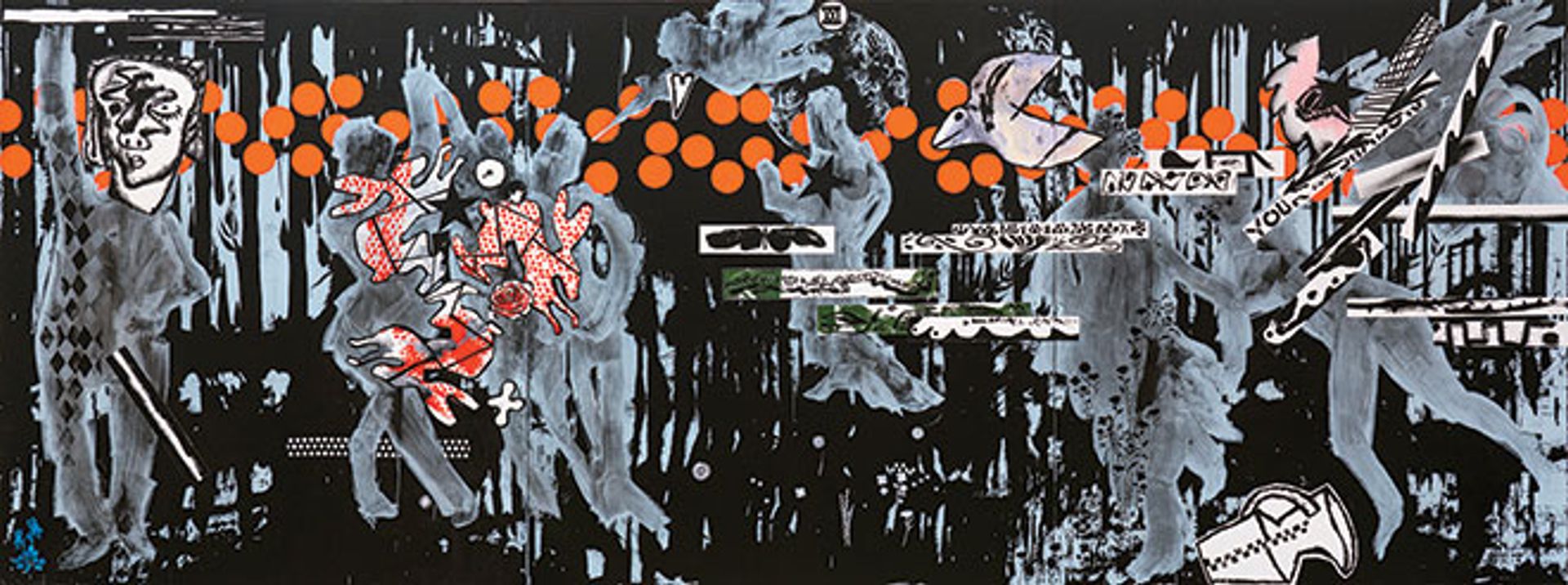

Andra Ursuţa’s Predators ‘R Us (2020) Courtesy of the artist; David Zwirner; Ramiken, New York © Andra Ursuţa

The Art Newspaper: There are three sections in The Milk of Dreams. Take us through them.

Cecilia Alemani: There are three themes. They’re really not sections, they’re more like the souls of the exhibition, which you will encounter in many different ways. The first one is the metamorphosis of the body and the definition of humanity. And in this particular theme, but also in general, the exhibition looks at post-human thought and philosophy—it really is the backbone of this entire show. So, thinking about challenging the Enlightenment and Renaissance idea of the man at the centre of the world. That, like everything else in the show, really comes not just from my interest in authors like Rosi Braidotti or Donna Haraway, but very much from the artists themselves. And that’s why the show also includes a wide majority of women artists and gender-nonconforming artists.

The second topic is the relationship between our bodies and technologies. This is, of course, a very broad theme, but one that became quite urgent during the pandemic. So, it thinks about our relationship before the pandemic with technology and technological optimism—the idea that technology and science and medicine could improve and perfect our bodies, so that we could live longer. And, on the other side, fear of a total machine takeover with AI [artificial intelligence]. This controversial or polarising relationship with technology has been exacerbated and turned upside down during the pandemic, in which we’ve realised how our bodies are extremely fragile and mortal. On the other side, in the very moment of this pandemic, the only way to be together is through technology, through the screen and the mediation of the many different devices that we carry with us. So, in a way, technology brought us together but also separated us.

The last theme is the relationship between humans and individuals and the Earth. This is another very broad theme and, in a way, the extension of post-human thought in particular: post-anthropocentric thinking about trying to imagine different kinds of relationships with what surrounds us, with the planet, with nature—one that is not based on a capitalist impulse, that is extractivist and about exploitation, but one that is instead non-hierarchical, about symbiosis and collaboration between ourselves and other beings. Rosi Braidotti often talks about the idea of “becoming Earth” but also, Silvia Federici, another very important philosopher, who has written in our catalogue, talks very often about this idea of “re-enchantment”—trying to find a relationship that is natural with what’s around us.

Remedios Varo’s Simpatía (La rabia del gato) (1955) © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, SIAE

The Milk of Dreams book is playful; it was created for Leonora Carrington’s children directly on the walls of their home in Mexico. Is there a playfulness at the heart of the exhibition, too?

There is playfulness, but the show is also very serious. The book is also a bit creepy, it’s a bit scary. I read it to my son, who is six, and he was like, “Mum, I don’t think this is a children’s book.” But those atmospheres, which are so present also in her paintings, are diffused in the show. There is a lot of irony and humour, but also, there is some seriousness. Especially when it comes to the themes of the body and nature and larger themes of ecology, I tried to have a more personal and introspective approach instead of just portraying the end of the world, which is probably very much happening, but…

You have “time capsules” in the show. The first includes Leonora Carrington and other Surrealists such as Leonor Fini and Remedios Varo, who have not had a presence in the Biennale up to now. They connect to the themes, but is it also about revisiting the canon?

Very much so. In the five thematic and historical capsules, I tried to do a more specific job of bringing to the fore the voices of artists that have been for too long excluded by the historical canon. Of course, I have no ambition of rewriting history, there have been plenty of exhibitions, like Fantastic Women or Radical Women that have already done this very important academic job. The capsules work more by analogies and rhymes. That’s also why they bring together artists from international Surrealism but also the Harlem Renaissance and Futurism. I tried to create a constellation of meanings that go a little bit beyond just the big art history. But in those presentations, too, you see a lot of humour and irony, making fun of the clichéd, very often sexist or stereotypical visions of women in those big Modernist movements.

I wanted to do a show that featured a vast majority of women: in Italy many of these discussions are still in medieval times

Do you have a rough percentage of how many women are in the show?

It’s a great number. I don’t have an exact number, because we haven’t necessarily asked for gender identification from the artists. But I would say it’s between 80% and 90%. The historical capsules are uniquely focused on women artists and that was very intentional, because I also looked at themes that historically have been connected to man. Programmed Art was such an important movement in Italy, and there is maybe one artist who is known who is female. The same when you think about the idea of the cyborg and Dada. I tried to show the other side of things. But for the rest of the show it came fluidly and naturally. I’ve always worked with lots of women artists. And then when I wanted to invite a man, I invited him. I didn’t sit down and have a percentage in mind. Of course, I wanted to do a show that featured a vast majority of women, especially because I want to remind people that this show happens in Italy, and in Italy many of these discussions are still in medieval times. So, of course, the show is international, but I hope it will also have symbolic value in Italy. For the first 100 years of this prestigious institution, the percentage of women artists in the show was less than 10%, and in the last 20 years it was around 30%. Numbers don’t matter but it is important to also reflect on the past, because that is just not a reflection of the world that we live in.

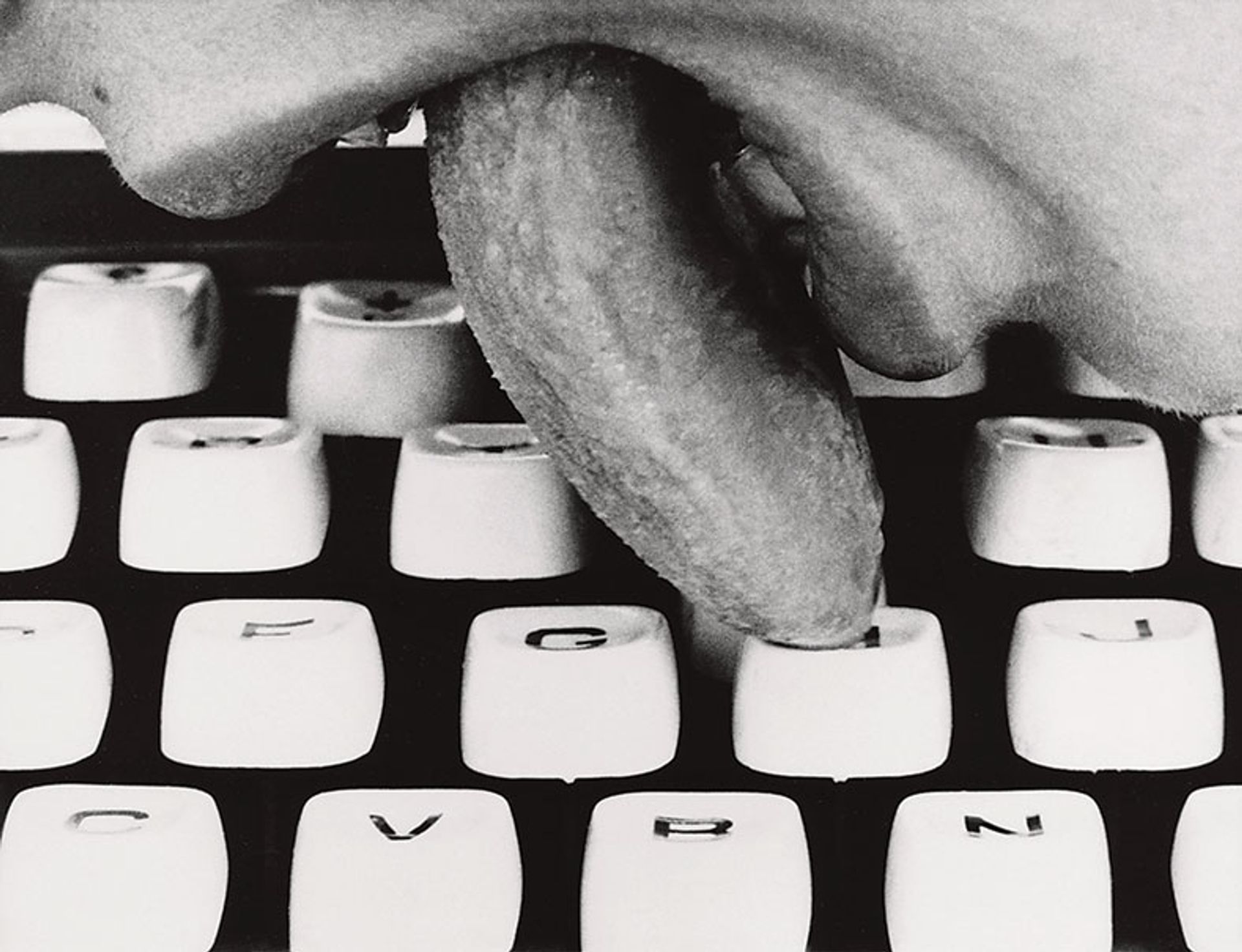

Lenora de Barros’s Poema (Poem) (1979/2014) Courtesy of the artist; Gallerie Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Vienna; Bergamin & Gomide, São Paulo

It’s a very physical show: even when you’re dealing with the concept of cyborgs, there’s a lot of sculpture. You have Lynn Hershman Leeson, a great digital artist, but also Marguerite Humeau, who deals with that subject sculpturally. Did you want to avoid too many screens?

It is a very physical exhibition. Of course, the experience of being in front of a film or video is also quite physical. But especially when I talk about technology, I do not mean that there will be virtual reality and augmented reality stuff. I don’t think there is even one, as far as I know. And somebody asked me about NFTs. As far as I know, there are none. You never know, [an artist] might hide it somewhere! There will be video but [cyborgs and technology] are not just the purview of video artists. There are lots of painters or sculptors who also tackle those themes.

You’ve worked with Formafantasma on the capsules. They’re designers who straddle all sorts of media. Why did you want to work with them?

I worked with them a couple of years ago in Venice, when we did this show about the history of the Venice Biennale, The Disquieted Muses. They’ve worked with me and our team for the entire installation of the show, so not just the capsules. But they do have a very hands-on approach to the capsule presentations. I decided not to work with an architect, partly because my main job is at the High Line, so I already work on a piece of architecture, and I’ve never really dealt with exhibition design in that sense—my space is given. I don’t necessarily know how to work with an architect. So I thought that, especially for the structure of the show, they could really help me in a more authorial way in these presentations, because they need a lot of care. Some of these rooms contain maybe 30 artists and maybe 80 artworks. So there is such attention to detail, which of course is also in the main show, but it’s at different levels. They’re extremely talented and I’ve enjoyed working with them.

You’re also looking at the history of exhibitions within the structure of

the show.

That was definitely one of the inspirations. The capsule about metamorphosis, which we also call the capsule of Surrealism, looks back at the very famous Surrealist exhibitions, which were so dense and rich—the first time that you hear talk about exhibition design in the 1930s. But we also looked back to previous exhibitions a lot. Each capsule has very much a different soul. So, the cyber capsule will have lots of metallic inflections, a very cold light. The capsule which we internally called the vessel will have a much softer, egg-like appearance. So they do feel different. You will feel transported into a different time zone or cultural atmosphere.

In your conversations with artists, were you talking to them about the content of the capsules?

No, because it was not necessarily that the two were in parallel. The idea of the capsules really evolved. Again, the genesis of my show is a bit bizarre, because the pace of it has changed so many times. It started really strong and then, all of a sudden, we had to take a break [because of the pandemic] and I did the show about the archive. It felt very organic but, in a way, it was also a completely different [kind of] research. So while I kept steady on the research on contemporary artists, and I met I don’t know how many hundreds and thousands of people via Zoom, for the historical ones it was more like academic research, with lots of archival research, books—which was amazing, because I had missed that so much. I was so happy not to talk to anyone on Zoom, at least for those capsules! Then I told most of the artists that there would be these presentations, but I did not want them to feel that they had to respond to the fact that in the show there is a certain Surrealist artist. So they worked completely independently, I did not share a list or too many details.

The pandemic is everywhere, both in the logistical structure, and in the artworks

In your introductory text, you write that you started to formulate your ideas before the pandemic but this show necessarily had to be a response to it.

The relationship with what’s happened in the world in these two years has been challenging and dramatic. But also, the impossibility of having a clear sense of the future, even in terms of the most banal logistical things, has been the most challenging part. When we announced the title last June, I would never have expected to be in this position, still now, where you can’t find the paper for the catalogue, you cannot find scaffolding poles, the situation with global shipping is an absolute nightmare. Nobody here—and this is an institution that makes hundreds of projects every year—would have thought about that. The pandemic is everywhere, both in the logistical structure, and reflected in the artworks. When it comes to the content of the actual works, you will see a very personal, introspective approach to the pandemic. There’s nothing that screams that X million people have died. Even the artists that are the most “political” went back to a language that is intimist and personal, still to convey very important issues, but it’s certainly not an exhibition that will scream that. It is not just a curatorial choice but it’s really a choice of artists who, like all of us, for two years found themselves in this bubble of suspension, a hiatus in which it’s impossible not just to plan but also to portray what’s happening in the world.

Six artists in The Milk of Dreams

We take a look at six contemporary artists whose work has been picked by Cecilia Alemani for the Biennale’s main exhibition

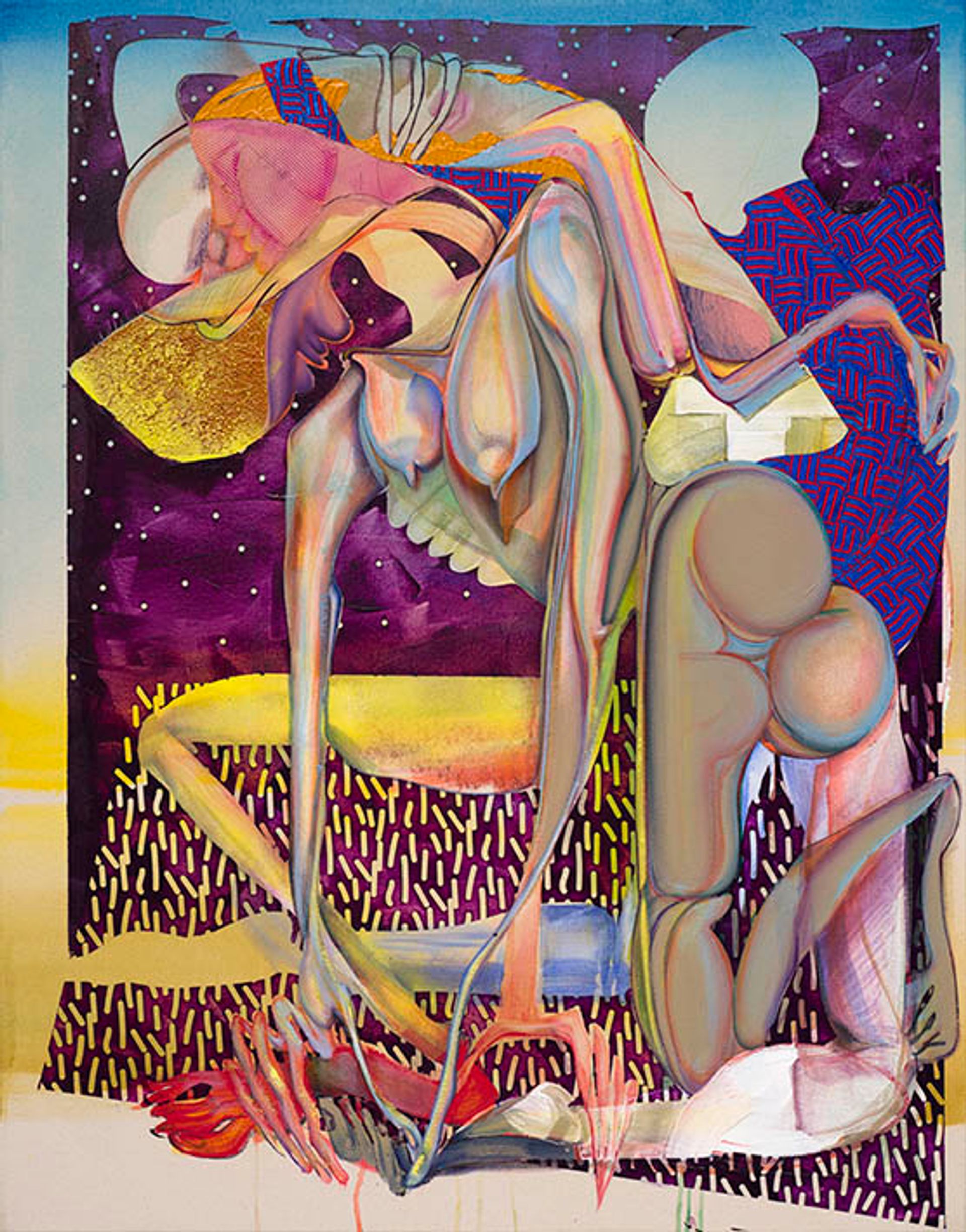

“Flashes of painterly exuberance”: Quarles’s Another Day Over (2022) Photo: © Fredrik Nilsen © the artist, courtesy of Hauser & Wirth; Pilar Corrias

Christina Quarles, Giardini, Central Pavilion

The Milk of Dreams opens with a “time capsule” of works by 20th-century Surrealist artists, and what Alemani describes as their “domain of the marvellous where anatomies and identities can shift and change”. Los Angeles-based Quarles’s paintings are a potent example of how artists continue to build on that Surrealist conception of the body: in constant movement, figures cavort, morph and warp within spaces that evoke digital landscapes and interiors, realised in high colour and flashes of pure painterly exuberance.

Human and animal forms: Berhanu’s Untitled LVII (2021) Courtesy of the artist; Addis Fine Art © Merikokeb Berhanu

Merikokeb Berhanu, Giardini, Central Pavilion

Alemani cites Berhanu as an example of artists who create “new forms of symbiosis between animals and human beings”, crafting “narratives that interweave environmental concerns with ancient chthonic deities, yielding innovative ecofeminist mythologies”. The Ethiopian artist, who now lives in Maryland, makes paintings that appear abstract at a distance, but clearly contain bodily aspects, as well as forms that suggest both landscapes and cellular organisms. Berhanu has said that her work evokes the rupture of her emigration to the US.

“Signs, symbols and private languages”: Von Heyl’s Primavera (2020) Courtesy of the artist and Petzel

Charline von Heyl, Giardini, Central Pavilion

Von Heyl is one of a number of artists who, Alemani says, adopt “signs, symbols, and private languages”—her paintings are both absorbing and elusive, each one an environment with its own language of shape and form. The painter Allison Katz, who was taught by German artist Von Heyl and also features in Alemani’s show, has said that Von Heyl decided to “paint like no one (not even herself)”. In doing so, she built a singularly slippery yet always fascinating oeuvre.

“Mortal and vulnerable”: Morelos’s Paisaje (Landscape) (2021) © the artist

Delcy Morelos, Arsenale

Following the time capsule devoted to the vessel—inspired by Ursula Le Guin’s essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, which argues for a literature inspired not by weapons but by bags or containers—is a section featuring a wealth of artists using ceramics. The Colombian artist Delcy Morelos draws parallels between the “mortal and vulnerable” qualities of clay and human bodies, in environments built from rich mineral-red ceramics. Drawing on broad sources, including Andean cosmologies and other indigenous cultures, she will create a “maze built out of earth” in the Central Pavilion, Alemani says.

A still from Leeson’s video Logic Paralyzes the Heart (2022), featuring actor Joan Chen Courtesy of the artist and Bridget Donahue

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Arsenale, Corderie

Alemani says that, in its final section, the exhibition “takes on colder, more artificial tones and the human figure becomes increasingly evanescent”. Enter Lynn Hershman Leeson, a trailblazer for artists exploring ideas of posthumanity. She studied biology and has been working with AI since 1995, exploring everything from bioprinting to genetic modification in her multimedia installations. For The Milk of Dreams, she is creating a new video that, Alemani says, “celebrates the birth of artificial organisms”.

A quintessential artist for the show: Pessoa’s Sonhíferas (2020-21) Photo: Daniel Mansur; courtesy of the artist; Mendes Wood DM

Solange Pessoa, Arsenale, Giardino delle Vergini

The show ends with a cluster of works in the outdoor spaces at the Arsenale. Brazilian artist Solange Pessoa’s sculpture is among many that “guide viewers to the Giardino delle Vergini along a path that leads through animal beings, organic sculptures, industrial ruins, and disorienting landscapes”, Alemani says. Pessoa’s soapstone sculptures seem at once evocative of the body and the landscape, born in the present but summoning a distant past.