It has been six weeks since Russia invaded Ukraine and started sending in heavy artillery and soldiers to wreak havoc and destruction on a peaceful country that only declared its independence 31 years ago, in August 1991.War in the region has been simmering since February 2014, when Russia started gathering at Ukraine’s borders following the Revolution of Dignity.

San Francisco-based artist Inga Bard was making art about that tumultuous time while it was happening. Born in Odessa, Ukraine in 1987, Bard’s earliest memories were of the reconstruction at the end of the Cold War and her family’s struggle to put food on the table.

“It was the wild west,” she says. “I was very young when the USSR collapsed and the only things I know about the lifestyle beforehand is from my grandparents' tales. The people who were well off and in the Communist party speak fondly of those times. Others had their family experience the great famine and were subjugated into essentially serfdom.”

Bard and her family immigrated to the US in 1997. She is the co-founder of two public art initiatives, Paint the Void and Art for Civil Discourse, and currently serves as the artistic director of MobileCoin, and along with curator Andrew Berardini launched the MobileCoin Art Prize that was first presented at the NADA Miami art fair last December. MobileCoin, founded by Bard's partner Joshua Goldbard, is currently working on a matching donation campaign for non-profit organizations that are raising money for humanitarian relief work in Ukraine, including the Ukrainian Students for Freedom.

“The war has affected me very deeply and I spent the first two weeks coordinating how to get my grandparents and friends' families out,” Bard says. “Witnessing this event has shaken me to the core of my being. I feel like I've come full circle in my identity. After leaving Ukraine to become an American, then a Californian, I now again feel so strongly connected to my Eastern European nature.”

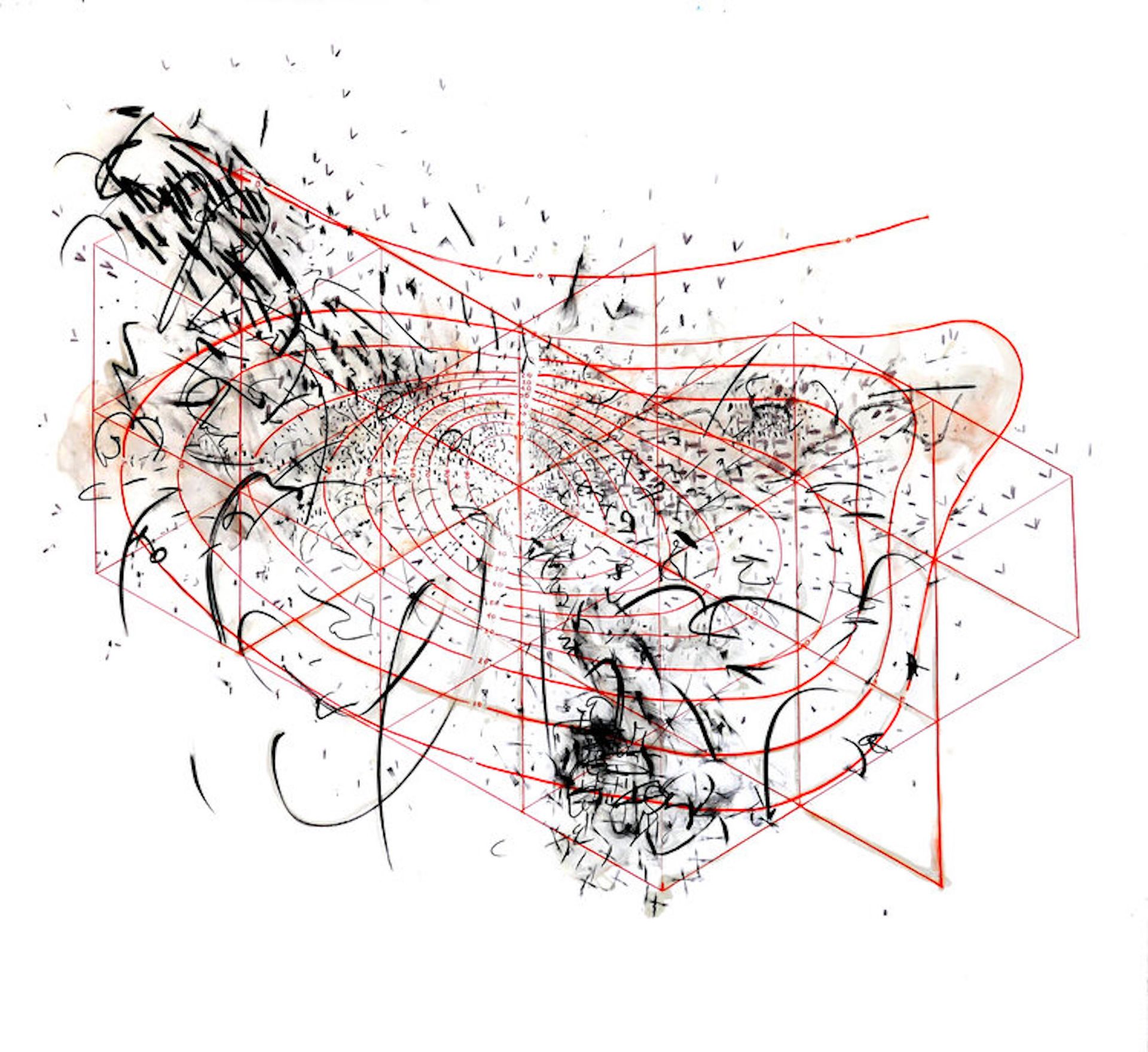

Yulia Pinkusevich, Casualty Isorithm 2, 2018 Courtesy of the artist

Artist Yulia Pinkusevich, also based in San Francisco, feels a similarly renewed connection to her Ukrainian heritage. Her ongoing series Isorithm (2018-present) takes inspiration from a Cold War-era military manual that outlines the impact of nuclear bomb blasts. “These works have allowed me to channel my overwhelming empathy and emotions someplace positive, which has proven to be of great comfort for me during this devastating time,” she says. In 2020, Casualty, Isorithm 2, was acquired at the deYoung Museum’s Open show by Karin Brewer, the curator in charge of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts.

Pinkusevich was born in 1982 in Kharkov, USSR, now Kharkiv, Ukraine. Her family was granted refugee status and emigrated to Brooklyn, New York in 1991.Her father’s family are Ukrainian Jews, her mother’s Siberian Russian. In 2015 she created the large-scale painting installation Silencing the Cacophony, which was inspired by Ukraine's Maidan uprising, and was exhibited at Kent Fine Art and the Ukrainian Museum in New York, as well as the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art in Chicago.

In 2021, Pinkusevich’s father moved back to Ukraine due to his failing health and the affordability of living there in his later years. But the war has upended the stable senior stage of life for which he moved back. “I’m terribly sad for all the people going through this,” Pinkusevich says. “The trauma will last for many generations.”

Ceramic artist Natasha Dikareva shares similar stories of resilience, also tinted with sorrow. She emigrated to the US in the 1990s, settling in San Francisco before moving to the East Coast during Covid-19. She was born and raised in Kyiv and her family, including her uncle, her cousin and his wife, as well as many friends have chosen to stay behind.

“My cousin is a professional cameraman and just got accredited to be able to shoot documentaries of this war,” Dikareva says. “He is ready to start but there are not enough bulletproof vests, helmets and medical kits. My uncle is handicapped and can't go to the shelter during the bombardment; his caretaker’s brother in Nicolaev was killed volunteering in the army.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Dikareva’s figurative sculptures have taken a dark turn, with once-serene faces now moaning in anguish and riddled with holes as if broken or shot to pieces.

Natasha Dikareva in the studio with recent work made in response to the war in Ukraine Courtesy the artist

Los Angeles-based multimedia artist and film-maker Yelena “Skye” Makarczyk witnessed the build-up to the war first-hand. “The last time I visited was in November of 2021. I crossed the border from Ukraine to Russia on foot, as the airlines weren’t flying directly between the countries, and I saw with my own eyes the tension at the border,” she says. “It was terrifying.”

Now she waits every nerve-racking day to hear from family and friends to ensure they are safe. “Many of my friends and classmates are now fighting in the war,” she says. “Many of them are film-makers. One is a railroad worker who took up arms. I get reports from them constantly and stay in very close touch.”

Among those she’s in regular contact with are a cousin who is a middle school teacher in Kryvyi Rih and another cousin who is distributing food to soldiers and civilian fighters near Dnipro. Along with her friend Alesia Daronichava, Makarczyk created a GoFundMe campaign to raise funds to support her cousins’ efforts. “When I talk to them, I’m amazed by the kindness they still carry in their hearts, waiting for the brutality to be over so they can rebuild Ukraine,” she says. “They believe they are fighting for their freedom to exist, for their culture to be passed on, for their children to be a part of civilized culture.”

Homes have been destroyed and lives lost all across Ukraine. Those surviving are gathering in shelters wherever they can, and art is prevailing. Makarczyk shared a video of artist Vasyl Pilka working in a bomb shelter in Kryvyi Rih. In the video, Pilka leans over a table carving a glass surface with a sharp tool. A copy of the US Declaration of Independence is underneath the glass. Since the Maidan revolution, Pilka has been using documents that define democracy as source imagery. The painstaking process is a commentary on labour and the materiality of the glass echoes the fragility of all that holds a society together.

“This war feels like betrayal to humanity, betrayal to nature, a deep knife wound into all that’s sacred and to be valued,” says Makarczyk.