History intrudes at the strangest of times. On 30 April 1945, Lee Miller photographed the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp for Vogue, trudging through the muck in military-issue army boots, and then travelled on to Munich with the 179th Regiment of the 45th Division. Miller and her colleague David E. Scherman found themselves in Adolf Hitler’s abandoned apartment on the Prinzregentenplatz; she hadn’t had the luxury of hot running water for three weeks, and so rinsed off the dirt of Dachau in a bath, overlooked by a photo of the Führer. By the middle of that afternoon Hitler had died by suicide in his Berlin bunker. A photo depicting Miller at this providential moment inaugurates Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945-1965, a snapshot that encapsulates a period display above all concerned with the intimacy and alienation of the mid-century home, with attitudes of individual self-presentation against the weight of global events, and with the grime left by the most devastating war.

What follows at the Barbican, the Brutalist complex built on a site of intense aerial bombardment during the Blitz, is a remarkable and often unexpected collation of work. Shirley Baker’s sensitive street photographs of working-class sisterhood on the hollowed-out terraces of Hulme in 1965 find a perfect pairing in Berlin-born Eva Frankfurther’s harrowing depictions of women on the margins. One work, West Indian Waitresses (around 1955), depicts the tiresome labour endured by the first Windrush generation in British hospitality and service industries, but a brief flash of eye contact betrays a begrudging comradery. A self-portrait of Frankfurther in a crimson dress, her black-brown eyes lost in the middle distance, in an extraordinary build-up of uneven pigment, remains with you long after leaving. Frankfurther, a Jewish refugee from Nazi persecution, completed the painting only a year before her suicide at the age of 29. We can only rue what else might have been made by this exceptional portraitist, whose brief career produced studies of timeless anguish when the afflictions of history have overwhelmed their subjects—and yet whose name remains relatively unknown.

Elsewhere, a consistent focus on design on both floors marries the elegant simplicity of functional homeware, such as a luscious vessel in cosmic dolomite glaze by Lucie Rie, with the avant-garde chaos of David Medalla’s kinetic umbrella-like sculpture Sand Machine (1963). These are all artefacts of “the insecure child of anxiety”, as the historian Tony Judt characterised postwar Britain, as much as they are documents of proud national regeneration. Of course, for the Conservative prime minister Harold Macmillan in 1957, it was the time when British people had “never had it so good”—but the gainsays are everywhere. Even a room dedicated to the plush verve of post-war utopia, in which Pop spokesman Richard Hamilton’s half-abstract vision of machines dressed up like fashion models dance against the backdrop of Alison and Peter Smithson’s elite House of the Future, feels like it can’t escape a crisis of scarcity and diffident self-presentation.

Postwar Modern could have very easily felt like the curatorial equivalent of one of those vintage BBC social documentaries of the late 1950s, and there are certainly aspects of what the self-taught photographer Roger Mayne called realism’s “search after truth”, but this is an exhibition that feels like a vivid evocation of a time without ever being overly didactic or intent on teaching a history lesson. It’s the surprising coincidences and correspondences that make it cohere, and while we might think we know the principal figures of this period—and Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon and David Hockney are all represented by brilliant canvases—there’s so much to discover.

The Warsaw-born artist Franciszka Themerson was a revelation, who described her visionary paintings as “battlegrounds, littered with casualties”, as the ferocious juts and jags of incisive lines suggest the razed roads of a city district seen from the air. But there’s a gentle humour here, too, and amid the plaster-textured vortex of Topography of Aloneness (1962) we encounter the unmistakably humanoid forms of overlaid eyes, arms and genitals; canny yet gentle figures, like cheeky street urchins. Another of her works could hardly be more different: Here is a man, a product of the state (1960), a polychromatic riot of poured and dripped paint, sees an amorphous blood-red border encroach upon a vague anthropomorphic body, whose bedraggled face is transfixed in complete confusion and his hand waves aloft as though making a salute. A hostile or authoritarian power may well have emerged in his sightline.

A global story

The curatorial team of Postwar Modern have sensibly delimited this story to work made by artists resident in Britain, but there can be no ignoring the fact that this is a truly global story, shaped by the refugees, immigrants and exiles who made new lives in Britain in the middle of the 20th century. When Frank Auerbach arrived in London in 1939 as part of the Kindertransport scheme, he was just seven; his parents perished in Auschwitz three years later. Still working every day at the age of 90 in his modest studio in Camden Town, Auerbach, who studied with Frankfurther at Saint Martin’s School of Art, has become one of Britain’s most celebrated artists.

It is not so much the ruins of bombed-out buildings that are shown in Auerbach’s densely impastoed paintings, but cavernous construction sites—the fierce girders rising into the sky, the lurid palette of the excavation, the grainy textures of the new capital. Auerbach made 13 major building-site paintings between 1952 and 1962: Rebuilding the Empire Cinema, Leicester Square (1962) proved to be the last of the series, and was completed with the rush and urgency of knowing it would be a completely transformed space even a fortnight later.

Auerbach’s long-term friend Freud is paired with a fellow German immigrant, the photographer Bill Brandt, and this room is a terrifying psychodrama of the male gaze. Brandt’s series of monochrome nudes sometimes find themselves framed by the cheap matchboxes and decaying fruit of the ration period or set against gaudy petit bourgeois floral wallpaper, but they are all sexually provocative portraits of female melancholia in claustrophobic interiors. They haunt and invade. We shouldn’t be there. But we get the sense that Brandt shouldn’t be there either. In this, these small-scale photographs are a perfect mirror to a young Freud’s narratives on the perpendicular wall: in Hotel Bedroom (1954), the agitated study of his new marriage to Lady Caroline Blackwood, who would soon abandon the artist, is palpably flattened out as husband and wife seem hemmed in together yet irretrievably remote.

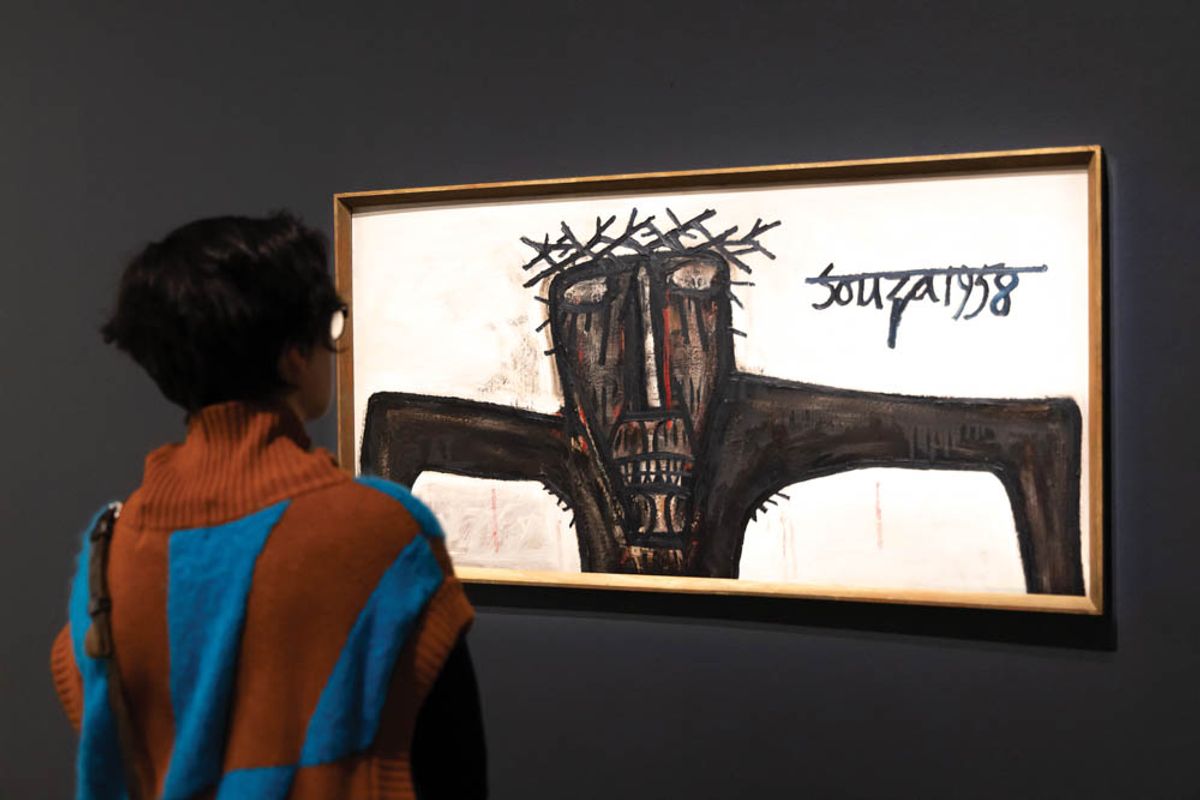

Many of the works on the expansive ground floor, such as Francis Newton Souza’s singular revisions of saints and Christ under extreme bodily and psychological assault, seem to recall the traumas of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and of the civilian brutalisation in war long after the fact. It is impossible to ignore their wretched relevance for our own moment. When Russia invaded Ukraine in the week before Postwar Modern opened on 3 March, we were told this was the return of history. But of course, history never went away. The works here remind us of the pain endured by civilians during modern warfare, in the heat of violence and afterwards, and the capacity of art to try and make sense of what that means. If history doesn’t repeat itself but rhymes, Postwar Modern feels less like a couplet but a screeching cry.

• Matthew Holman is Lecturer in English at University College London