Last year, I attended an exhibition by a mid-career Black artist presenting a new body of work. The works were figurative and monumental. The artist had created a fictional ancient kingdom in which god-like Black figures peopled an Arcadian landscape. In piece after piece, these figures worked, played and loved, with firm glutes and rippling chest muscles. It was impressive, breath-taking even, but as I wandered through the exhibit, I wondered, where were the pot-bellied and love-handled?

Kerry James Marshall has spoken about the absence of the Black figure in the Western art canon. One only has to walk through the museums in London to test the accuracy of his statement. At the National Portrait Gallery, starting on the top floor with Henry VII and his Tudor descendants, white men and women gaze at the viewer, dressed in the hoses and corsets of their time.

After several rooms, you might chance upon Thomas Jones Barker’s The Secret of England’s Greatness. In this painting from around 1862-63, Queen Victoria presents a Bible to a kneeling ambassador from East Africa. His portrait might be the first you see of a Black person after an hour spent in the museum. And he isn’t even standing.

Thomas Jones Barker’s The Secret of England’s Greatness (around 1862-63)

It is no wonder then that Black artists have rushed to fill this vacuum. In Kehinde Wiley’s paintings, young Black men in hoodies and sneakers, rear triumphantly on horses. In Amy Sherald’s, Welfare Queen, a slim, regal Black woman with a crown on her head, gazes majestically at the viewer. In Kerry James Marshall’s Past Times, his upper middle-class Black subjects play golf, picnic by a river, jet ski and steer a motorised boat.

Kehinde Wiley, Equestrian Portrait of Philip IV (2017) in the collection of the Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, OK

As I think through these works by these important artists, a question forms in my mind. Do Black artists who make figurative work, feel pressured to present a noble, aspirational image of the Black body that challenges both the deliberate erasure and the racist tropes of the Western art canon? And if indeed, some Black artists feel this pressure, what about more ambivalent narratives around the Black body, less inspirational, more introspective. Is there space for these Black artists?

It is why I am drawn to the work of Nkechi Ebubedike. Born in Baltimore in 1984 to Nigerian parents, Ebubedike studied Fine Art at Carnegie Mellon University and has a Master’s degree from Central St Martins in London. Her earlier works were conventionally figurative, drawn in a realist style. As her practice developed, inspired by Francis Bacon and Phyllida Barlow, her figures became heavier, more weighed down and distorted.

How do you find a figure that encapsulates the emotional and psychological weight of being Black in the West? Ebubedike’s artistic experimentations move her ever closer to answering this question. Ebubedike’s Black bodies contort, squat to defecate, loll submerged in water, with eyes that gaze past the viewer, lost in their own psychological world. She paints the Black figure from the inside out.

Nkechi Ebubedike, Nude on Wood Block (2020) Image: © the artist, courtesy of Tafeta

In Nude on Wood Block, a Black figure balances precariously between two plinths. The head and neck rest on one plinth, while the torso and legs rest on the other. The figure’s back curves in a smooth line but the strength of the body is compressed. The image is startling, uncomfortable to look at and yet, also, strangely beautiful. The figure has achieved a balletic grace by somehow contriving to keep their balance.

The figure in Nude on Wood Block isn’t based on a real person. However, any Black person who has ever contorted themselves to appear more palatable, by switching their accent or adopting a European name for example, will instantly recognise the emotional and psychological truth of this image.

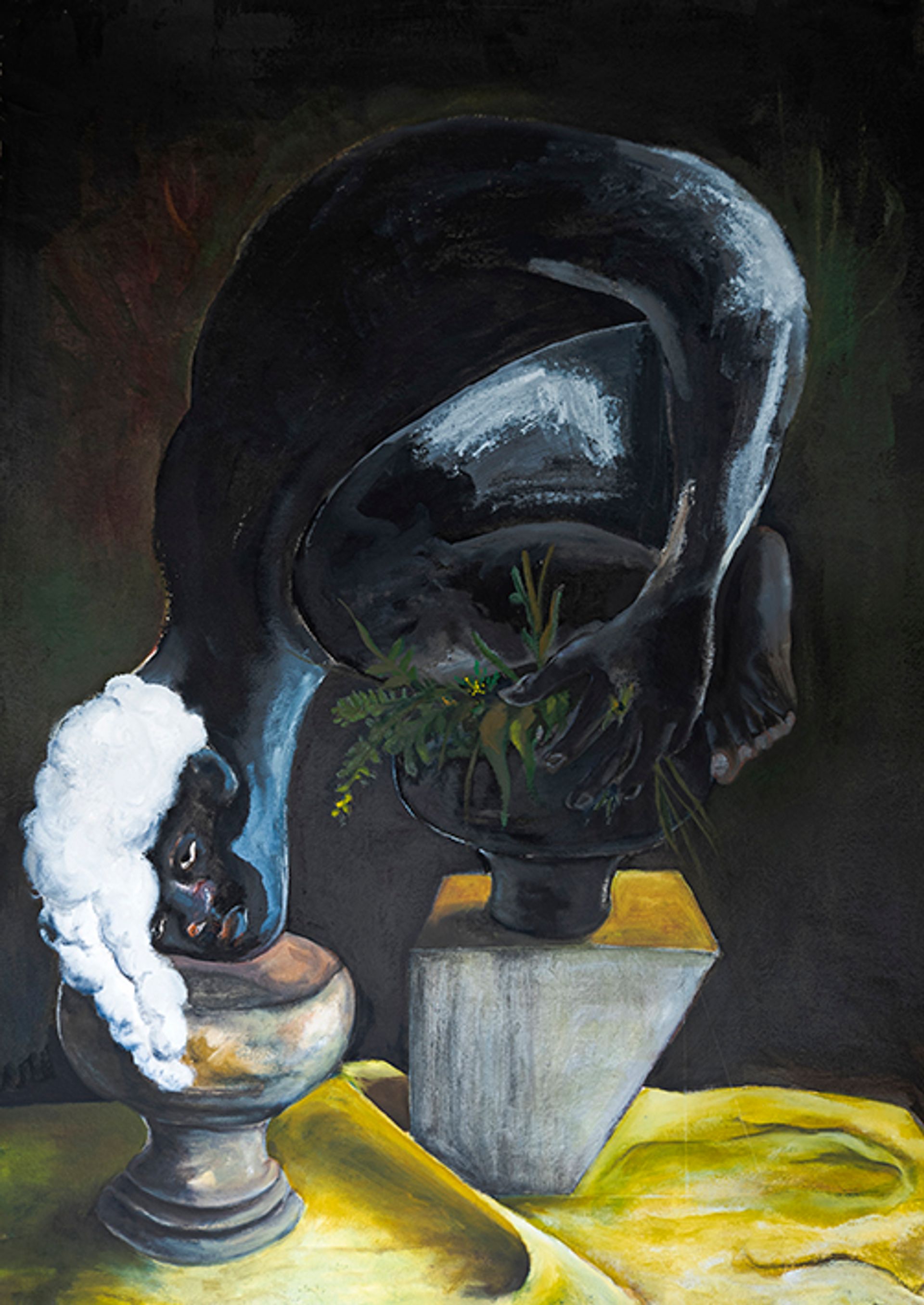

In Ebubedike’s most recent work, seemingly surreal elements have been introduced. In Partitions, a black leg protrudes from a wall and a severed hand juts out of a wooden block. What does this dismembered Black body mean? I’ve heard it said that a lot of Western "civilisation" was built on Black bodies. For example, with the wealth generated from the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. With the chopped hands of the Black labourers on King Leopold’s rubber plantations in the Congo, whose labour built his Belgian palaces. With the Black roots of Rock and Roll, Jazz and viral Tiktok dances. Our contributions may not always be acknowledged but we’re in the foundation of the house.

Also, in the West, cultural, political and economic gatekeepers who are often still white, want bits of blackness, chopped up and appropriated to serve their own purposes. But they don’t want the Black body whole. They prefer it dismembered. It’s hard to look at Ebubedike’s work without flinching. Perhaps it’s why she’s not yet better known.

I love the inspirational and aspirational portraits of Kehinde Wiley, Bisa Butler, Arthur Timothy, Amy Sherald, Ben Enwonwu, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Akinola Lasekan, Lina Iris Viktor and on and on the list goes. I love to see the Black body dignified, ennobled, put on a pedestal and dressed with a crown. But blackness is not a monolith. There is not just one way to be Black and there is not just one way to present the Black body in visual art. So in this month’s column, I celebrate Nkechi Ebubedike’s experimentation and look forward to seeing what she does next.

• Chibundu Onuzo is a novelist and fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Read her monthly column Slade to Zaria here