Most children could draw a castle: a pointy tower at each corner, a moat, battlements, a drawbridge. And, if skilful enough, a galloping knight. Their castle would look very like the last example in John Goodall’s fascinating book, Walt Disney’s Cinderella castle, based on the Sleeping Beauty castle built in 1955 at Disneyland California, a version of which has been the film studio’s logo since 1985.

Goodall himself helped to nail this image of the archetypal castle in his gigantic book, The English Castle (Yale 2011), with its ravishing cover photograph of Bodiam (East Sussex) glowing in golden light, its towers and battlements reflected in the water. His new look at some of the most imposing buildings in Britain is very different from that treasury of glossy colour photographs, floor plans and scholarly essays. This time each castle gets one short chapter, a rather grimy tipped-in photograph and the words of the people who commissioned them, built them, lived in them, admired or feared them.

Even the idea of a castle is shifty, less solid than its stone walls

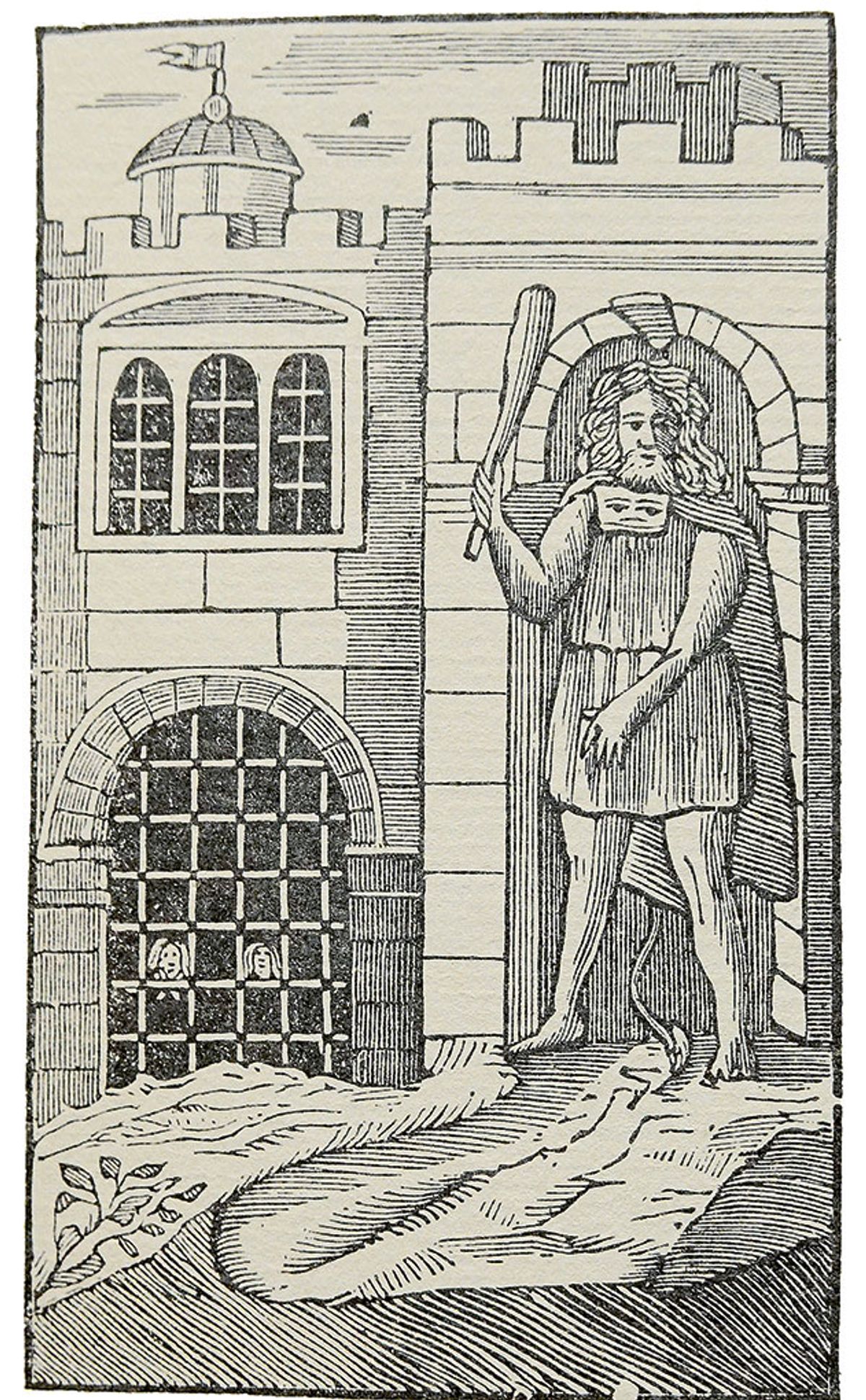

His eyewitnesses, winnowed from inventories, court cases, letters, poems and novels—Horace Walpole’s 1764 Ur-gothic shocker, The Castle of Otranto, is there along with Doubting, Blandings and Hogwarts castles (the creations of John Bunyan, P.G. Wodehouse and J.K. Rowling respectively)—grippingly shift the viewpoint from that of the omniscient outsider. In the 12th century a contributor to the annals known collectively as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle wrote bitterly: “They greatly oppressed the wretched men of the land with castle-work; then when the castles were made, they filled them with devils and evil men.” Unfortunates vanished into the castles “where they were tortured with unspeakable tortures”. Castles as prisons had an astonishingly long history. In March 2011 the remaining prisoners left Lancaster Castle, aka HMP Lancaster, the last medieval castle in Britain in such use.

Even the idea of a castle is shifty, less solid than its stone walls. Most of Goodall’s castles, symbols of authority built to shock and awe, rose after the Normans began stabbing them into the landscape like Monty Python’s great stamping foot. However, his first castle is far older, Bamburgh (Northumberland). In 655 AD, according to local monk the Venerable Bede, writing 80 years after the event, the villainous Mercian king Penda attempted to burn it down. Bede describes Bamburgh as a city, not a castle because, Goodall suggests, he would have known descriptions of Rome and Jerusalem within their gated walls like a castle’s defences.

If castles often serve now as heritage days out with cream tea in the dungeon, that repurposing also has a long history. By the 19th century wealthy antiquarians were restoring castles for education and entertainment as well as private homes. Trains, bicycles and then private automobiles brought them within reach of millions. The patrician contempt for such day trippers also has a long history. Kenilworth (Warwickshire) is one of several castles for which Goodall’s chronological approach allows repeat visits: we see Henry V spending Lent there in 1414, and then in 1899 Henry James visits, grumbling at “twopenny pamphlets and photographs” and “beery vagrants sprawling on the grass”. “I had learnt that,” he continues, “with regard to most romantic sites in England, there is a constant cockneyfication with which you must make your account.” If as a peasant I have to choose between being admitted for the unspeakable tortures or among the jolly cockneys, mine’s a pint and a fruit scone, please.

• John Goodall, The Castle: A History, Yale, 400pp, 75 b/w and colour illustrations, £18.99/$26 (hb), published 22 March

• Maev Kennedy is a freelance arts and archaeology journalist and a regular contributor to The Art Newspaper