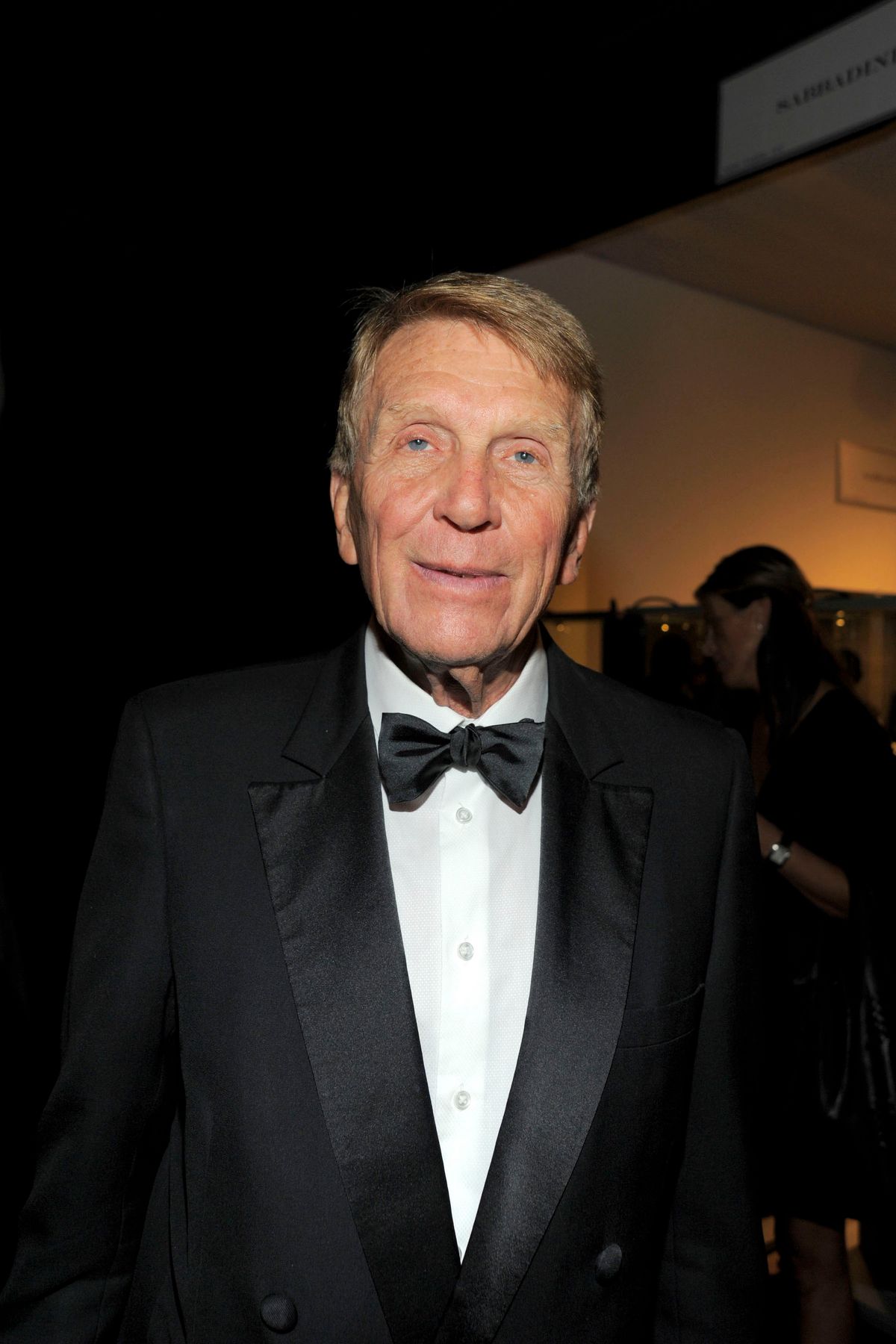

Ashton Hawkins, the longtime head lawyer for the Metropolitan Museum of Art who pioneered the practice of art law, died on 27 March of complications from Alzheimer's Disease. He was 84.

Tall, blonde, courtly and affable, Hawkins was known for his friendships with New York’s elite, many of whom were Met benefactors. He often accompanied wealthy women to charity events, earning him the nickname “curator of donors”.

Hawkins’s social connections ranged from Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis to Gerard Malanga of Andy Warhol’s Factory, who visited his home with Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick. “Edie came with Andy and a group of people, including Gerard Malanga, who was carrying a bull whip,” Hawkins said. “Andy, Edie and I sat down together for drinks and marijuana. For a while everything was going along fine, until Malanga took off his shirt and cracked his bull whip a few times to get our attention. Andy and Edie continued to chat without paying attention to him, and my housemates were quite amused.”

Hawkins started at the Met in 1969, hired by the flamboyant populist Thomas P. F. Hoving. He would stay until 2001. The museum was scrutinised by smaller institutions for all its legal activities—claims on its collections, deaccessioning, its admissions policy, traffic on Fifth Avenue and race relations. “I think it was the first institution to have a position called ‘counsel to the trustees’, and that was Ashton,” says Monroe Price, the former dean of Cardozo Law School in New York who knew Hawkins for decades.

“He had a stunning curiosity, and a sense of fairness, which made him the perfect person to moderate a debate with people who disagreed with him,” says Marc Porter, chairman of Christie’s for the Americas, who interned in Hawkins’s office at the Met in the early 1980s.

In the 1993 memoir Making the Mummies Dance, Hoving acknowledged Hawkins’s skills as a legal fixer. The Met, a smaller place then, also relied on Hawkins to raise money.

Hawkins’s years at the Met saw a rise in claims on works that it held—colonial spoils, Nazi war loot or illegally exported objects. The most prominent of these was the Euphronios krater, a sixth century BC vase from Italy which came to the Met in 1972 through a middle-man for a dealer in Beirut. Italian authorities said the work was smuggled, yet Hawkins responded publicly and in a law review article that they had no proof. In 2006, the Met agreed to return the vase to Italy.

“So many of the good things, including many of my friends, flow from Ashton,” says Patricia Sullivan, a longtime friend and a member of the book club that Hawkins founded, The Proust Group, specialising in classics, that continues to meet monthly. “He was incredibly generous in putting people together, in connecting people.”

In 1985, while still at the Met, Hawkins became chairman of another institution, the Dia Foundation for the Arts, and stabilised the place known for eccentricity and debts, renaming it the Dia Art Foundation. Some in the de Menil family, the original source of its funding, held hard feelings.

In February 1996, Hawkins was rushed out, two months earlier than his planned forced departure, under pressure from the board. Dia’s new director at the time, Michael Govan, was building a new regime. Hawkins said Govan forced him out. The Dia coup coincided with the addition of wealthier trustees than Hawkins had recruited. The soft-spoken Hawkins, who addressed disputes quietly, collided with iron-fisted philanthropy. Press coverage was updated daily as bold-faced names skirmished. Govan saw it as a triumph for Dia. He did not respond to requests for comment.

After retiring from the Met in 2001, Hawkins, along with a group of collectors, museum leaders and lawyers, founded the American Council for Cultural Policy (ACCP) to respond to the “retentionist” attitude toward the global antiquities trade.

“Much of the problem does not flow from deliberate policy but from overreaching law-enforcement, from politics,” Hawkins said in 2002, “we believe that legitimate dispersal of cultural material through the market is one of the best ways to protect it. We’re interested in the protection of culture as much as the protection of legitimate collecting.”

Yet that message never caught on with the public, which tended to support the return of objects removed from “source” countries and sold to collectors in the US, Europe and Japan.

“The current climate of opinion has shifted in favor of national retention of cultural material, and the archeological viewpoint has prevailed over the art historical view,” says lawyer William Pearlstein, a founding member of the ACCP. “This conflicts with the more open system contemplated by the 1970 UNESCO Convention and the US implementing legislation. But Ashton would likely say that opinions and laws evolve over time and that a better balance may be reached in the future.”