Past visitors to Kelmscott Manor, the silvery stone house in an Oxfordshire village which the English designer and political firebrand William Morris described as “heaven on earth”, found his wife Jane’s bedroom looking just as they might expect. It was “a blizzard of willows”, as the curator Kathy Haslam describes it, papered and hung with Morris’s still-popular Willow Bough pattern—inspired by nearby willows growing along the banks of the river Thames. On the wall was a pre-Raphaelite portrait of Jane framed by willow branches, painted by Charles Fairfax Murray after Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The decor was convincing and yet completely wrong, as new research behind a £4.3m conservation project of Kelmscott proves.

The Morris family’s 17th-century Cotswolds retreat and its cluster of listed farm buildings will reopen to the public on 1 April, after two years of closure for extensive repairs and conservation, and new additions including a thatched education building. The project was awarded a National Lottery Heritage Fund grant in October 2018. Every room has been emptied, researched and redisplayed, and lost features reinstated, all using traditional materials espoused by Morris, who founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in 1877.

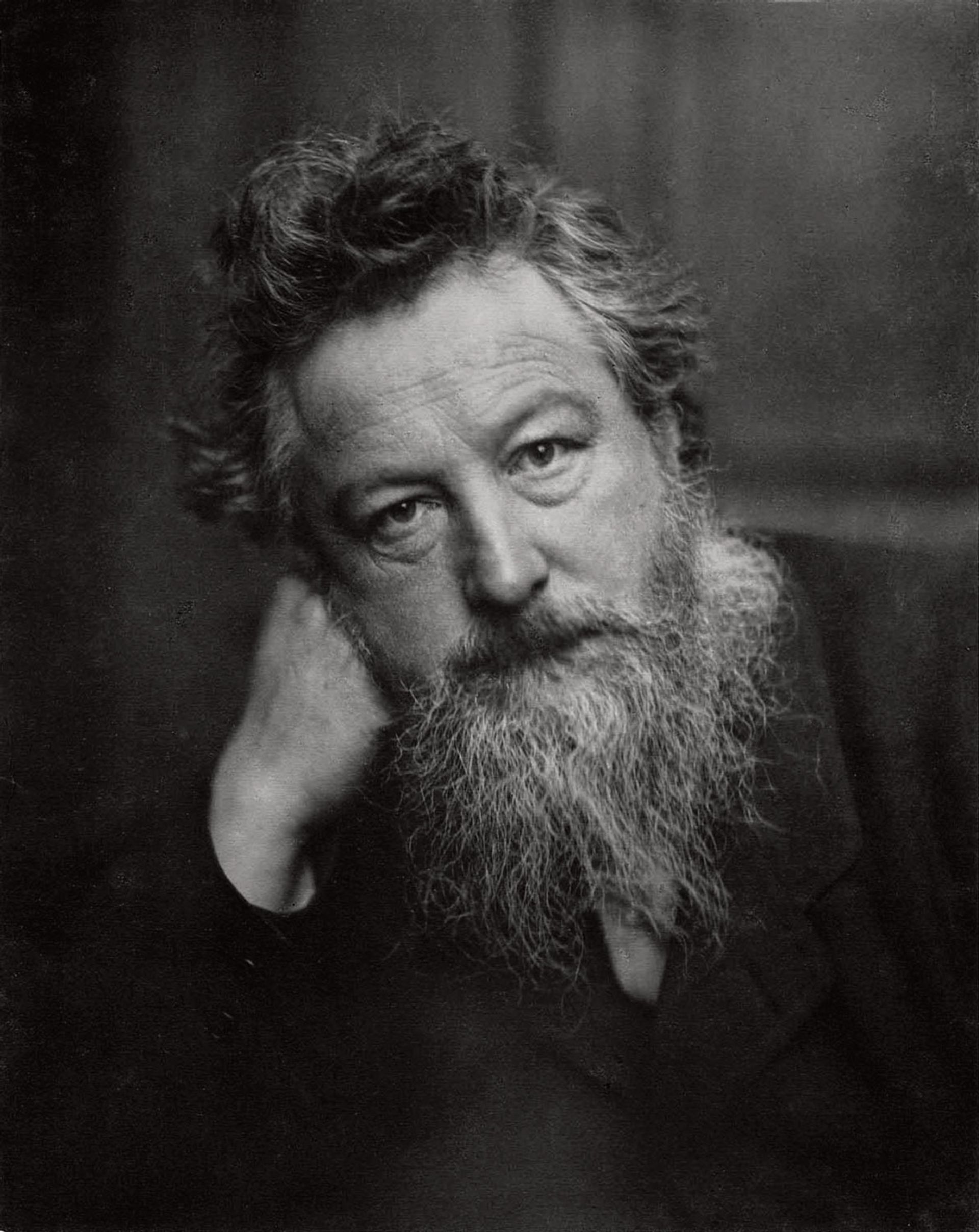

William Morris (1834-96) Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Paintings, photographs, diaries and letters helped the team to identify objects that had been in storage since the 1960s, when the Society of Antiquaries of London took over ownership of Kelmscott. The University of Oxford originally inherited the house and its contents from Morris’s daughter May in 1939 but declared it could no longer maintain the property after 20 years of struggling to find tenants happy with no electricity or modern amenities.

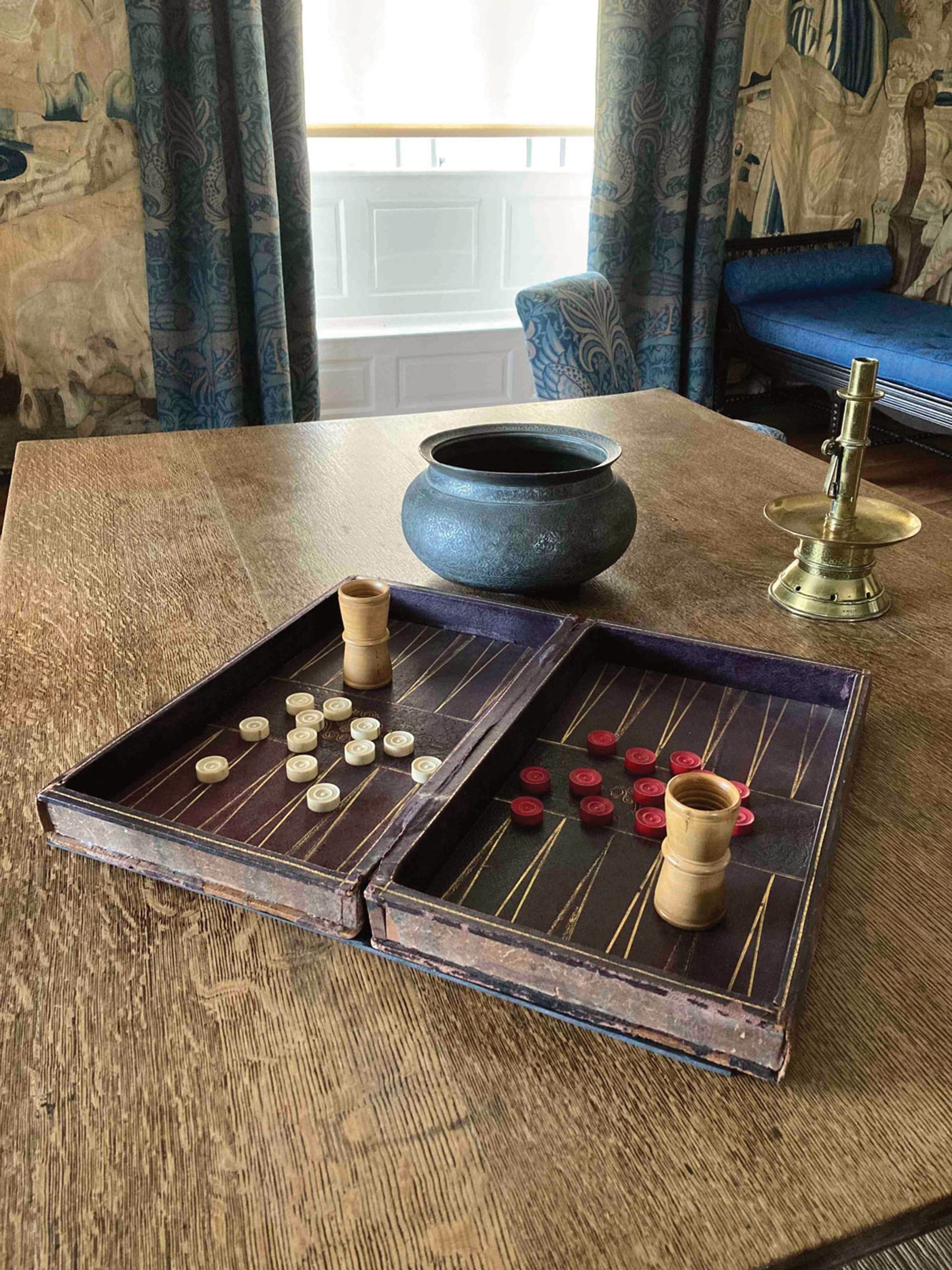

Recent finds that will be incorporated into the revamped displays include a backgammon board disguised as a leatherbound volume and candlesticks traced from a description of evening candles shining softly on Sheffield plate. Some deceptively simple tasks left Haslam sympathising with the 1960s workers who attempted to replace a single tread of a spiral staircase only for the entire structure to collapse. The “green room” is now much greener since paint scrapes from a rediscovered wooden overmantel, designed by Philip Webb, revealed the original rich dark shade. However, bringing back the overmantel involved rebuilding the ceiling, which had sagged so it no longer fit.

William Morris's rediscovered backgammon set Photo: courtesy of the Society of Antiquaries of London (Kelmscott Manor)

Jane’s bedroom is at the heart of the house’s saddest story: her love affair with Rossetti, who leased Kelmscott Manor with her husband in 1871. Morris wanted to conceal from the public gaze the growing relationship between two people he loved. Rossetti stayed, creating yearningly sensuous drawings and paintings of Jane, while Morris left to explore the wild landscape of Iceland, collecting crafts and sagas as he went. Both the affair and the friendship burned out as Rossetti’s behaviour became increasingly challenging; the marriage endured.

Today the revived bedroom is no longer a willow bower. A fascinating set of photographs by Frederick Evans, commissioned by Morris months before his death in 1896, prove that the four-poster bed (in which he was born in 1833) was in fact hung with a cheerful Regency chintz of 1829, now recreated with its heavy fringe trim. The wallpaper was a Morris design but the much more colourful Blue Fruit, specially hand-printed from the original wooden blocks at vast expense. The effect is one of high Victorian comfort rather than Bohemian rhapsody.

Late 19th-century photographs of Jane Morris's bedroom helped the team to recreate the chintz hangings on the four-poster bed Photo: courtesy of the Society of Antiquaries of London (Kelmscott Manor)

Kelmscott is surprisingly remote, with a pub but no school, shop or public transport. The Lottery money—and the prospect of extended opening hours (Thursday to Saturday) and visitor traffic—raised alarm among some villagers, even fears of Disneyfication. One local gate has no fewer than three notices warning off anyone thinking of parking beside it. The property manager at the manor, Gavin Williams, hopes eventually for an electric vehicle link to the nearby market town of Faringdon, which can at least be reached by bus. He insists all visitors to the house will be confined to a car park on the edge of the village, that residents are fully on board, and that peace has broken out in heaven on earth.