Lizaveta German is in a maternity hospital in Lviv, four days overdue with her first baby and two days before Russia attacks the city in western Ukraine, when she speaks to The Art Newspaper.

German, the co-owner of the Kyiv gallery The Naked Room and co-curator of the Ukraine pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale, fled her home in besieged Kyiv a few days earlier. “I stayed in the city for about a week [after the Russian invasion]. I was sure I wouldn’t leave, but due to my circumstances and urgent need for medical assistance, we decided to leave for a safer place,” she says via Telegram. “A lot of the artistic community are now in Lviv—the city centre is crowded with artists and art managers. I see a lot of friends here.” Meanwhile, German’s business partner and fellow Venice curator, Maria Lanko, has managed to get to Italy to work on realising Pavlo Makov’s installation for the Ukraine pavilion.

Back in Kyiv, the gallery is shut and most of its staff have left Kyiv, though two are helping to evacuate some of the most valuable works to Lviv. “Obviously, this is difficult as it’s not easy to secure transport,” German says.

The gallery is trying to stay in touch with its artists too—they are now spread around Ukraine and a few of the women have managed to cross the EU border (most men are not allowed to leave the country). “There are a lot of artistic residencies and scholarships for Ukrainian artists right now, so it is possible for female Ukrainian artists to find shelter, a place to work and earn money,” German says.

The Shelter (2022), a recent drawing by the Lviv-based artist known as Kinder Album, represented by ArtEast gallery

Others, however, have stayed in Kyiv, “to protect the city”, or with their families in eastern Ukraine. For example, in the heavily shelled city of Kharkiv, the artist Vitaliy Kokhan is volunteering with the humanitarian operation. “So far, as far as I know, all are safe and in quite a good mood,” German says.

The Naked Room has launched the Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund (UEAF), administered by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) NGO, to help the country’s artists and cultural workers, providing a list of emergency residencies, relocation schemes and other opportunities. It started “out of necessity”, German says, “because from day one we were getting messages from curators and artists offering to help.” She adds: “A lot of artists are in need—they need money to cover their everyday needs and protect their family because they lost their ability to earn money in these horrible times.” German hopes it “will continue when the war is over and we need to rebuild our country—that will be when funds will be in huge need”.

Masha Khalizieva, a representative of the Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art and the UEAF, says the UEAF raised almost $10,000 in the first few days. "Our next step is the launch of the Emergency Art Shelter," Khalizieva says. "This project developed by our friends and partners, Forma Architects, is about constructing shelter for the artists who lost their homes and studios, providing them with a safe place to live and work."

Funds are crucial, Khalizieva says, but equally important is the attention and recognition of the broader art world, which she says "is unfortunately massively corrupted with Russian money and its false imperialistic narratives."

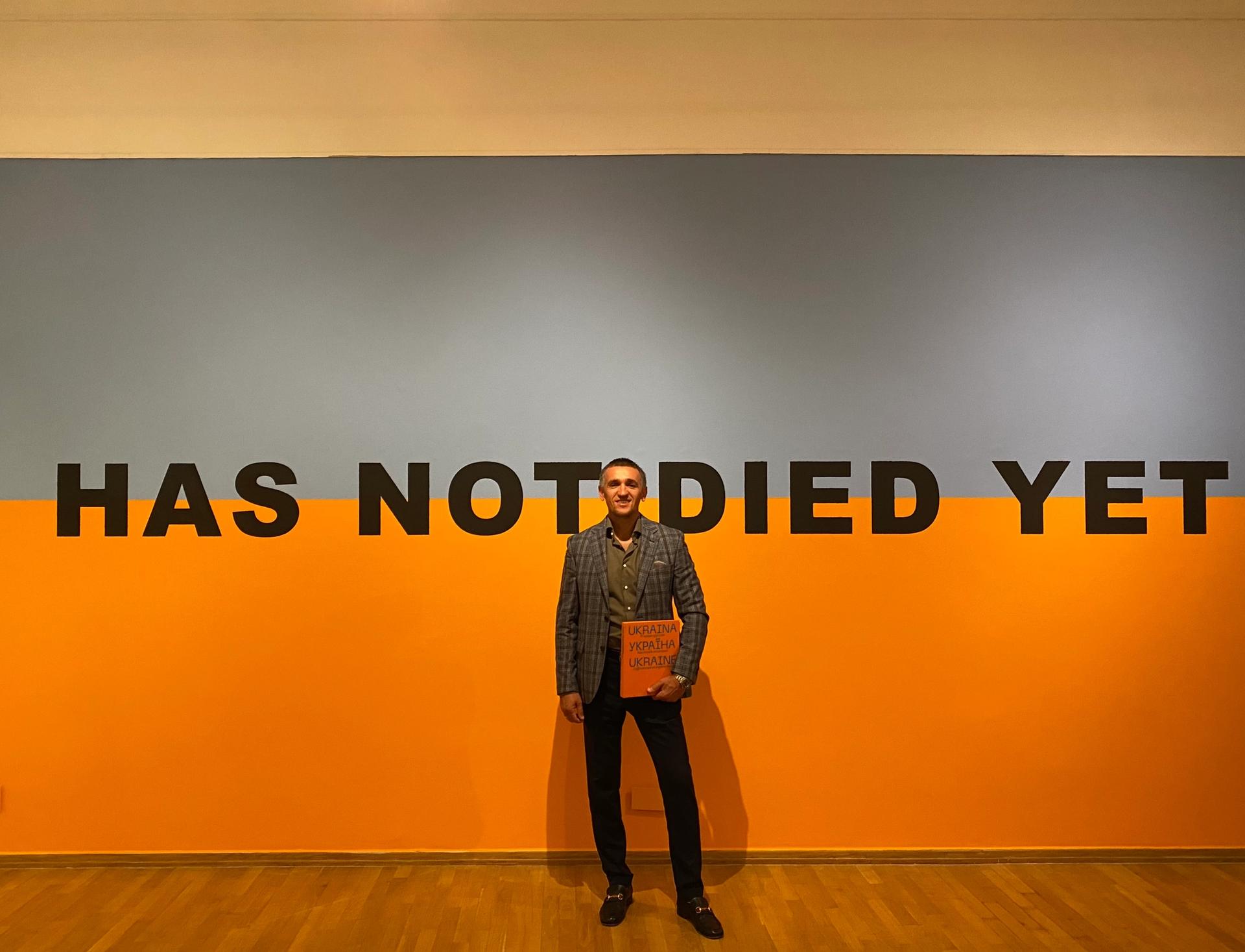

Igor Abramovych, the founder of Abramovych Art Agency

Courtesy of Abramovych Art Agency

Building bridges

Another commercial gallery that has launched an emergency fund is the Berlin- and Kyiv-based ArtEast Gallery. Speaking from Berlin, Cornélia Schmidmayr, the co-founder and managing director, says the gallery is now concentrating its efforts on its Peace for Art Foundation, an endowment fund launched in mid-March, aimed at helping Ukrainian artists and protecting the country’s cultural heritage. Schmidmayr’s Ukrainian business partner, Ivanna Bogdanova-Bertrand, has left their Kyiv office locked up and is now in Paris with her French husband. “The challenge now is far bigger than the gallery and just selling art—we created a foundation in France very quickly, to build a bridge between Western and Eastern Europe,” Schmidmayr says.

Many of the gallery’s artists (including women) have chosen to stay in Ukraine. “We represent 11 Ukrainian artists, and as far as I know only one has left and one already lived in Berlin,” Schmidmayr says. “Some left Kyiv for the countryside but now it’s no safer than the city, as the Russians are already in the countryside.” How are these artists feeling? “It’s a mixture of feeling very frightened, of wanting to resist, and of wanting to help.”

Until May (or later if funds allow), any artist still in Ukraine and in need of immediate financial support can apply to the Peace for Art Foundation for an emergency €200 stipend for everyday needs. The foundation is also taking applications from Ukrainian artists, curators and cultural institutions who are seeking funding for art projects.

Many artists want to help by selling their art to raise funds—but getting it out of the country is the challenge. “Photography is possible—many artists are sending us the digital files so we can protect them and print them in Germany,” Schmidmayr says. “We are working on emptying their studios and getting their works to safety, but this is dangerous and difficult… We have a network there, [so] I will drive to the border to collect the works.”

Voloshyn Gallery in the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, is currently being used as a shelter. Courtesy of Voloshyn Gallery

Elina Dorokhova, the art manager at the Kyiv-based Abramovych Art Agency, has taken her children to Slovakia, where she feels "enormous support from the state." She says that "collectors from Dubai, Europe and the US have been actively supporting Ukrainian artists by acquiring their works for private collections...everybody’s eyes are on Ukraine now." Dorokhova's colleague, art director Viktoria Kulikova, says the company is looking to "evacuate at least some of our works to Europe" and points to invaluable support from arts organisations outside Ukraine, such as Burlington Sculpture Park in Massachusetts, Niwot Sculpture Park, Colorado, and Sculpture by the Sea in Australia which have "organised special events to raise funds for the Ukrainian army and sculpture sales to support our artists. It is a great honour for us to install the works of Ukrainian artists, acquired by regular US citizens, in public spaces."

Igor Abramovych, the founder of Abramovych Art Agency, says: "What is unfolding on the territory of our country right now is no 'armed conflict.' It is the genocide of the Ukrainian nation." Of the artists he works with, he says the older generation (Oleg Tistol, Anatoliy Kryvolap, Mykola Matsenko, Vasyl Tsagolov, Viktor Sydorenko and Marina Skugareva) are in Kyiv and in Kharkiv. The younger ones (such as Roman Minin, Egor & Nikita Zigura, Nazar Bilyk, Oleksii Zolotariov, Daniil Shumikhin, Andrey Sydorenko and Dmytriy Grek) are either out of the country or in western cities, like Lviv and Uzhhorod.

"Some of my artist friends are actively helping the war effort. Some are saving lives by helping their families and other civilians," Abramovych says. "Some had been discharged from the armed forces on medical grounds and are now involved in humanitarian relief efforts. They all hope to return to their studios. In their moments of downtime in bomb shelters, they keep sketching out new works."

Several years ago, Abramovych began work on his eponymous sculpture park, next to his home just outside Kyiv. It was supposed to bring together the works of more than 20 Ukrainian artists in what he hoped would become a new cultural landmark. But now, he says, "the site is besieged and mined by the occupiers that keep razing Kyiv’s outskirts to the ground."

Max and Julia Voloshyn, who founded Voloshyn Gallery in Kyiv in 2016, are still in Miami, having caught Covid after exhibiting at Art Basel Miami Beach in December. “We are staying here for now, because we can do much more here than in Ukraine,” Julia says, adding “we have a little daughter, her safety is a priority for us. We will return to Ukraine as soon as it’s safe and possible.”

Sergei Sviatchenko's work in the Abramovych Sculpture Park on the outskirts of Kyiv

Courtesy of the artist and Abramovych Art Agency

Back in Kyiv, their gallery, which had not been damaged at the time of writing, is being used as a shelter: “Part of the gallery staff and artist Nikita Kadan now live there. At the beginning of the war, two more families of our artists lived in the gallery, who later moved to western Ukraine. Now our Kyiv gallery serves as a shelter, as it did during the Second World War.” Some of the gallery’s artists have stayed in Kyiv, others have left “for safer cities or abroad”. For many gallerists and artists, Julia says, “the question of evacuating works abroad remains open, as it is currently impossible to do so”.

The war has, for the worst possible reasons, brought international attention to Ukrainian art, something German, Schmidmayr and Voloshyn hope continues. “When the war is over, do not forget Ukraine and its artists,” Schmidmayr says. German describes culture as “a sort of battleground—this is a moment that the Ukrainian artistic community can raise its voice and show we are not just war victims, we are a country of extraordinary artists and intellectuals…Of course, the war, and all the people who have lost their lives and their homes, is too high a price to pay for this recognition.”

So, as Julia Voloshyn says: “Let’s stop this war.”