A glitzy ceremony will mark the 94th Academy Awards on 27 March, but The French Dispatch, written and directed by seven-time nominee Wes Anderson, is not up for a single Oscar. Not for Anderson’s signature cinematography that makes everything look like a pastel vintage postcard, and not for Best Original Screenplay (despite the film’s unusual magazine-style format, complete with a prologue, three short stories and an epilogue).

And so The French Dispatch will claim zero gilded figurines, but its cast of oddball characters has still captivated audiences and longtime New Yorker readers since the film’s release last October. The movie is Anderson’s cinematic love letter to the weekly magazine, which he began reading in high school and collects in bound volumes. Much digital ink has been spilled over which New Yorker writers or profile subjects inspired which French Dispatch personas.

For the artiest of the film’s short stories, “The Concrete Masterpiece”, we know for instance that Julien Cadazio (played by Adrien Brody) is based on legendary art dealer Joseph Duveen as profiled by S. N. Behrman in a 1951 article, “The Days of Duveen.” And fictional art critic J.K.L. Berenson (portrayed by Tilda Swinton) is modeled after Rosamond Bernier—a writer and connoisseur who lectured about art while donning dramatic ballgowns, once profiled by Calvin Tomkins.

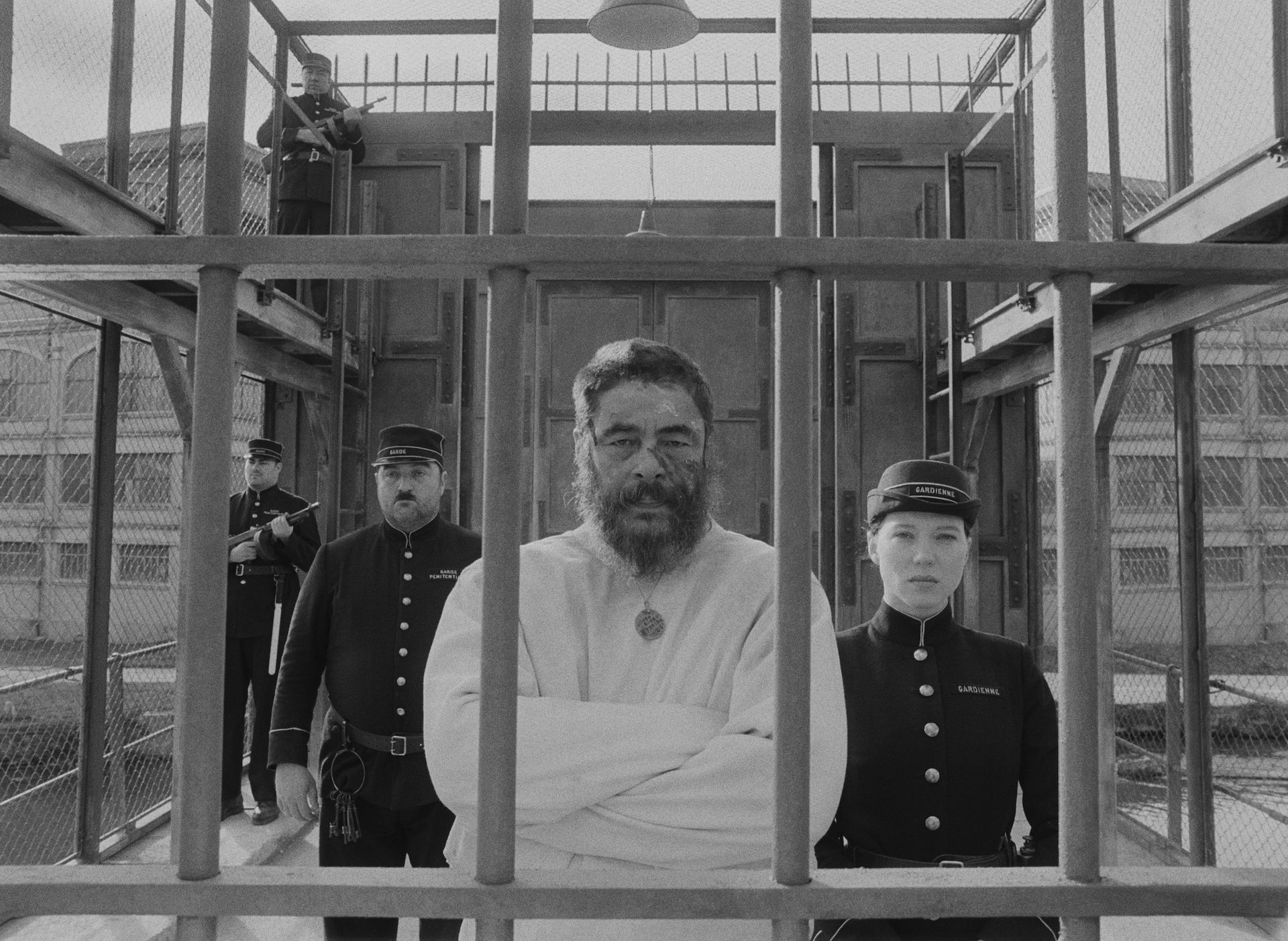

Benicio del Toro (centre) and Léa Seydoux (right) in the film The French Dispatch Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2021 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved

One character who has been snubbed (not unlike The French Dispatch by members of the Academy) is Upshur “Maw” Clampette, a moneyed art collector from Kansas who goes to extraordinary lengths to extract a multi-paneled abstract fresco from the walls of a federal prison. (The polyptych mural was painted by a tortured artistic genius, played by Benicio del Toro.) “Nobody has an eye for things nobody has ever seen like Maw Clampette of Liberty, Kansas,” says Cadazio of the visionary collector, played by Lois Smith.

When asked who inspired Clampette, Anderson told The New Yorker that Behrman’s description of Duveen includes “a woman, a wife of one of the tycoons, I can’t remember which one, who talks a bit like a hillbilly”. (This might explain her name, a pun on the Clampetts from American sitcom The Beverly Hillbillies.) Anderson also shares that Clampette was partially inspired by Dominique de Menil who co-founded the Menil Collection in Anderson's hometown of Houston, except that Menil was Texan whereas Clampette—and her art collection set amid cornfields—is decidedly from Kansas.

An eccentric collector importing the avant-garde to the agrarian Midwest calls for an equally Midwestern role model (and Menil was a Frenchwoman living in the American South). There are certainly some historic contenders hailing from America’s middle states. And so without further ado, our nominees for Midwestern art pioneers à la Upshur Clampette are...

Mary Quinn Sullivan

In New York, Mary Quinn Sullivan is known as one of the founding mothers of the Museum of Modern Art. But back in her native Indianapolis, she was known for leading the Gamboliers—a group who paid annual $25 dues to acquire art that was a ‘gamble’ (or in other words, by artists who were not established). Their mission was to enrich the collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art with works by promising (and still affordable) youngsters, and between 1928 and 1936 they acquired around 160 works by artists such as Toulouse-Lautrec, Matisse and Modigliani that became the earliest modernist works in the museum’s collection. Sullivan picked each one herself.

Mary Atkins

Mary McAfee Atkins, around 1900. Ephemera Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Archives.

Like Clampette, Mary Atkins wanted to share her love of fine art with her Kansas (City) neighbors. Atkins was a schoolteacher who was born in Kentucky and moved to Kansas City after marrying a childhood friend who had made some savvy real estate investments there. Later in life she started making regular visits to a niece living in Europe, where she discovered a love for the Louvre and other art museums in Paris, London and Rome. Folks in Kansas City were shocked to discover, when she died in 1911, that this frugal lady had an estate of almost $1m and she had left a third of it to her adopted city to acquire land for a public art museum—now the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Marjorie Merriweather Post

Born in Illinois and raised in Michigan, Marjorie Merriweather Post became one of the world’s richest women when she inherited the Postum Cereal Company from her father in 1914. She directed Postum for decades and long after it became the General Foods Corporation, using profits from being an early adopter of frozen foods to give philanthropically and collect art. While living in Moscow with her third husband, who was the US ambassador to Russia from 1937-38, she bought jewelry, chalices and other art objects that number among the finest Czarist collections outside Russia. This Russophilic collection is on view at her Hillwood Estate home in Washington, DC, which she bequeathed as a public museum.

Charlotte Partridge

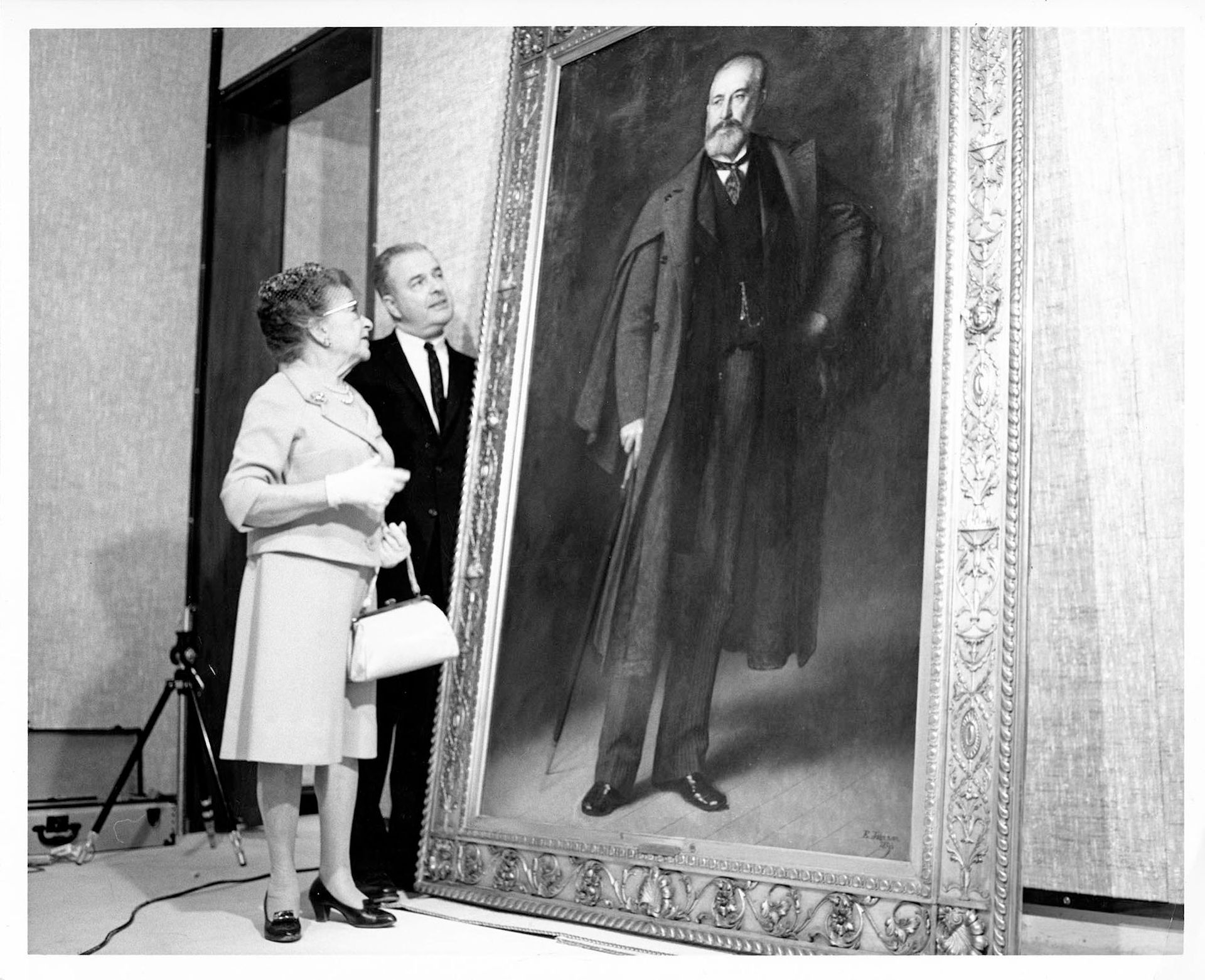

Charlotte Partridge and John Doyne standing in front of The Portrait of Frederick Layton (by Eastman Johnson) in the Milwaukee Art Center galleries in the mid-1960s Courtesy of the Milwaukee Art Museum

The capital that Charlotte Partridge—who measured under five ft tall but was a legendary dynamo—contributed to the Milwaukee Art Museum was the vision and energy that she brought to her 53-year involvement with the institution. Unlike Clampette she didn’t acquire art herself, but she enlivened Milwaukee by importing modern art through loan exhibitions, opening and directing an art school, and creating a dedicated gallery for local Wisconsin artists. When Partridge was promoted to director of the Layton School of Art and curator of the Layton Art Gallery (now the Milwaukee Art Museum) in 1922, she was one of few women holding senior positions at American art museums.

Bertha Honoré Palmer

Anders Leonard Zorn, Mrs. Potter Palmer, 1893. Potter Palmer Collection. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Chicago is a major destination for lovers of Impressionism thanks to tastemaker and socialite Bertha Honoré Palmer. “In Chicago we don’t buy Renoirs,” the president of the Art Institute of Chicago (which acquired Palmer’s personal Impressionist collection using the $500,000 she bequeathed the museum) once told a visitor. “We inherit them from our grandmothers.” This particular grandmother personally imported works by Monet and Degas from France during trips in the early 1890s, buying paintings from Paul Durand-Ruel (a Duveen-level dealer) and advised by painter Mary Cassatt. Palmer’s collection has been on view to Chicagoans since 1922 and is still the core of the museum’s Impressionist holdings.