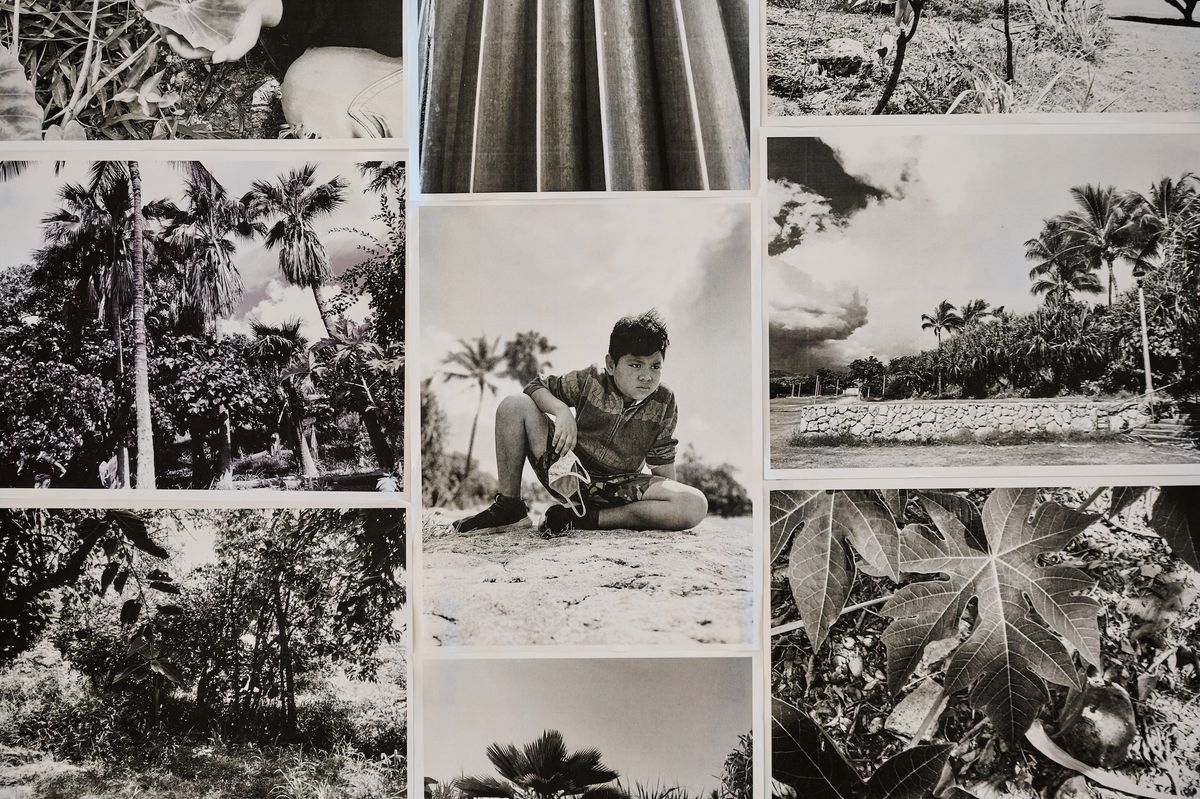

The year was 1972. Terrilee Kekoʻolani, then a young native Hawaiian activist, is pictured in a black-and-white photograph at a Save Our Surf (SOS) demonstration on Oʻahu’s east end. “We need to protect our resources, and stop land development and evictions of our people,” Kekoʻolani said. “We need to remember that Hawaii belongs to Hawaiians.”

This and other significant moments from the ongoing sovereignty movement, as documented by photographer Ed Greevy and the late scholar Haunani-Kay Trask, play out along a wall-filling installation at the Honolulu Museum of Art—all challenging dominant notions of migration, access and power that surround them in the inaugural Hawaiʻi Triennial, titled Pacific Century — E Hoʻomau no Moananuiākea.

More than 40 artists and collectives from around the world are featured in the exhibition, which is installed at cultural institutions along the southern coast of Oʻahu. A handful of attractions, like Jennifer Steinkamp’s evening light projections at Iolani Palace and Double A Projects’ “global-free store” at the Royal Hawaiian Center, popped up as limited-time interventions. The vast majority of the works, however, will remain on view until 8 May, collectively offering a robust, kaleidoscopic look at Hawaii’s urgent social and political dilemmas.

Leeroy New, Taklobo, 2022, at the Foster Botanical Garden Credit: Photo courtesy of Hawai‘i Contemporary, photography by Kelli with an Eye Photography / Kelli Bullock Hergert

According to official exhibition literature, the Hawaiʻi Triennial’s curatorial framework speculates on the Asia-Pacific region’s rise to prominence and the concurrent decline of Euro-American economic and cultural supremacy. Influential voices from these regions are apportioned generous real estate at all of the triennial's locations, each presenting their own distinct historical continuities, contexts and concerns. Other participating artists elude the east-versus-west dichotomy altogether.

Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, one of the three curators behind this iteration (with Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden director Melissa Chiu and author and curator Miwako Tezuka), tells The Art Newspaper that the curatorial team made a concerted effort to acknowledge the complexity of Hawaii’s histories. “This place is so much more nuanced than what it has been marketed as or made into,” Broderick says. “There’s more to the triennial than what we think. The same goes for the artists and the communities they’re fighting for.”

Dan Taulapapa McMullin Aue Away musical and dance performance, performed by Kaina Quenga and Anthony Aiu with music composed by T.J. Keanu Tario (Lady Laritza LaBouche) © Courtesy of the artist / Honolulu Museum of Art

At the heart of Pacific Century is an exhibition-wide effort to destabilise what Broderick has characterised as a rampant culture of “paradise economics”. From Ahilapalapa Rand’s tribute to Mauna Kea volcano on the island of Hawaiʻi at the Bishop Museum, to Herman Pi‘ikea Clark’s exploration of “Poʻo ʻOle”—a Hawaiian name that translates to “headless” but is used to describe a state of endlessness—at the Royal Hawaiian Center, many of the triennial's pieces directly address and dismantle insidious systems of exploitation that continue to grip the archipelago.

Nowhere is the critique of paradise economics more explicit than in artist Lawrence Seward’s widely-circulated project. A total of 5,000 limited-edition copies of the Seward Sun (2022), a fictional tabloid featuring news articles about an imaginary island resort, have been distributed on stands at various participating venues, all free and available to the public.

Published 12 years in the future on 18 February 2034, the 20-page paper offers a chilling snapshot of local and international affairs, covering issues like micro-plastic-borne diseases, global climate challenges and a new surfing record, courtesy of the “Disassociated Press”. Perhaps the most prescient dispatch is a story that expounds on Western sanctions on Russia amid “aggression in the Ukraine”, which are described as “the most drastic since 2022”. (Russia’s war on Ukraine began less than a week after the fictional paper’s publication.)

The games of empire—and the compartmentalised realities they spawn—are the defining motifs of this triennial. For University of Hawaii professor Gaye Chan, one of the founding artists behind the guerilla gardening project Eating in Public (2003-present), capitalism itself is on trial, which means ideas around identity and community take a back seat to practice. Members of the EIP operation style themselves after England’s 17th-century Diggers, planting free food gardens on private and public land, and setting up stores for open access to establish “autonomous systems of exchange”. For the triennial, EIP hosted a private event called Moveable Feast, educating visitors on the benefits of the non-native amaranth plant.

“There’s this violence about the invasive species rhetoric that is very nationalistic,” Chan tells Broderick in a video for the triennial. “There’s this confusion that everything that’s not native comes to be understood as invasive, and I think that’s not only incorrect, it’s dangerous in these political times when all over the world there’s increasing antagonisms against people that are seen to not belong.”

Installation view of Nā Maka O Ka ‘Āina (Eyes of the Land), a documentary series of educational videos by Joan Lander and Puhipau screening at the Hawaiʻi State Museum of Art © Nā Maka O Ka ‘Āina / Courtesy of the artists and Hawaiʻi State art Museum / Photo: Brandyn Liu

In the exhibition materials, EIP extends its ideas about indigeneity and invasiveness beyond horticulture, stating that the project “does not refer to specific plants but is, rather, a concept that is driven by political ideologies about belonging”. EIP’s expansive approach to belonging contrasts with Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina, a documentary series dedicated to the cultural and practical survival of the Hawaiian people that is also on view.

Launched in 1981 by film-makers Joan Lander and Puhipau, the series endeavoured to document the social and environmental movements that emerged from the islands a decade prior, many of which were directly aimed at reversing policies that contributed to native displacement and land abuse. To the benefit of tourists, locals and natives alike, some 666 minutes of unreleased footage from these films are screening in a dedicated room at the Hawaii State Art Museum (HiSAM).

Momoyo Torimitsu, Somehow I don’t feel comfortable, 2021, nylon, air blower, sound. At the Royal Hawaiian Center, Waikīkī Courtesy of the artist and Hawai‘i Contemporary. © Momoyo Torimitsu. Photo: Lila Lee.

According to Broderick, all of the pieces featured at the HiSAM will continue to be exhibited past the triennial’s 8 May closing date until the end of 2022. Highlights from this portion of the exhibition include heartbreaking works by the late Wayne Kaumualii Westlake, whose poetry and artistic collaborations figure prominently, as well as a dazzling study room stocked with scholarly texts on native Hawaiian history and culture contributed by ‘Ai Pōhaku Press.

For Broderick, the extended display of the triennial works at HiSAM will allow for a deeper impact with local audiences. “When a triennial leaves, it leaves a wake of exhaustion, devastation and broken relationships,” he says. “I appreciate thinking about how some of the efforts of this triennial will last beyond its duration. The issues get to move forward a little bit.”

Hawaiʻi Triennial 2022, Pacific Century — E Ho‘omau no Moananuiākea, until 8 May, various locations.