It might be said that ceramics are having “a moment”. The art form has long been gaining prominence and parity with other media in contemporary art, but it feels more visible than ever.

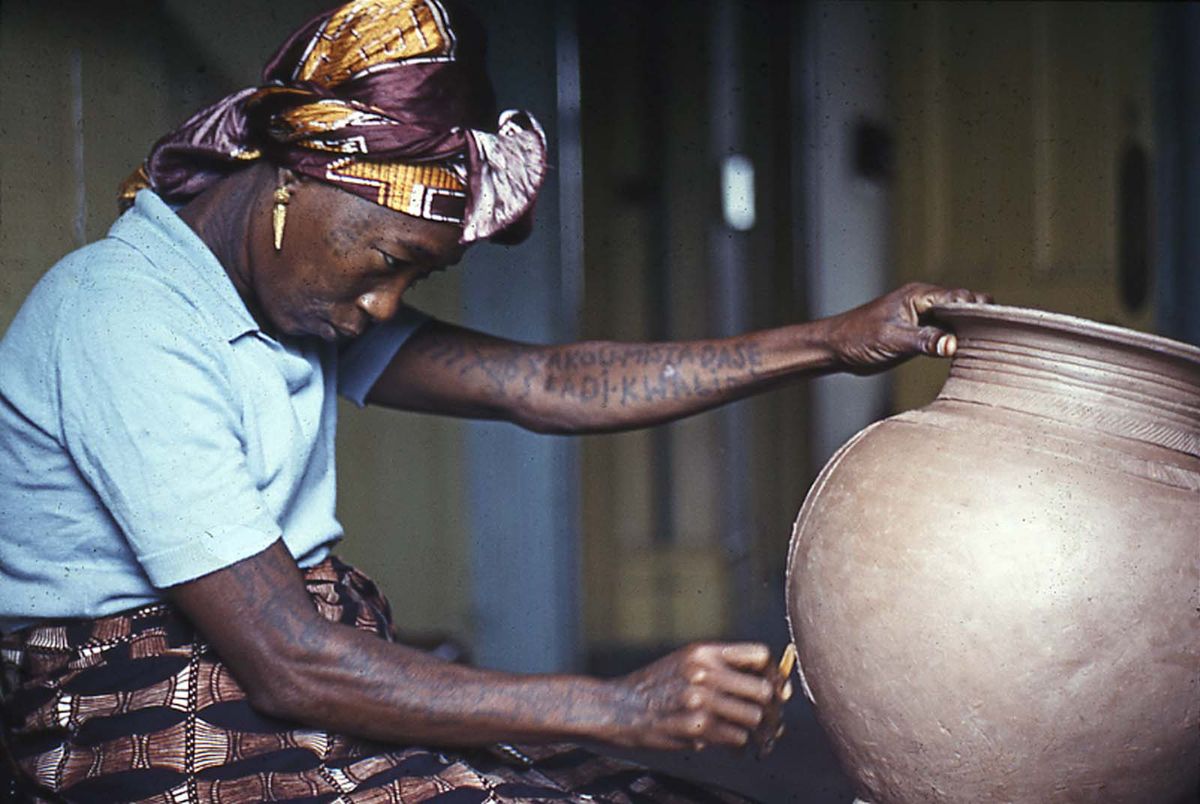

Last year, one of London’s best shows was A Clay Sermon by Theaster Gates at the Whitechapel Gallery, both a potted history of ceramics (and its attendant cultures) and a revelatory display of Gates’s recent work in the medium. This year, Body Vessel Clay at Two Temple Place in London (until 24 April) reflects on Nigerian ceramic traditions, their colonial collision with English studio pottery and their legacies in contemporary British art. In his current show at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, UK (until 19 June), Ai Weiwei continues to probe vessels’ meanings, associations and value, while also in Cambridge, at the Fitzwilliam Museum (until 24 July), the Kenyan-born, British-based artist Magdalene Odundo, one of the stars of Body Vessel Clay, sets her own vessels in the context of global historic ceramic traditions (see interview, pp 44-45). In the autumn, the Hayward Gallery in London will open a 25-artist survey of contemporary clay and ceramic art.

Perhaps most notable in an international sense is ceramics’ centrality in the Venice Biennale (23 April-27 November). When Cecilia Alemani introduced the concept of The Milk of Dreams, her exhibition at the heart of the Biennale, last month, she cited the speculative fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin’s essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction as a key text. Taking the idea that the earliest cultural invention was not a weapon but a container or vessel, Le Guin offers a critique of literary forms that privilege the weapon-branding (of course, male) hero and “the killer story” and instead proposes “that the natural, proper, fitting shape of the novel might be that of a sack, a bag. A book holds words. Words hold things. They bear meanings”.

So, too, works of art. And a whole section in Alemani’s show will reflect this, with works by late 20th-century artists working with clay and fire, including Tecla Tofano, with contemporary artists including the Colombian Delcy Morelos and Odundo. This link couldn’t be more powerfully expressed than in Clay, Jade Montserrat’s performance, filmed by the duo Webb-Ellis, in Body Vessel Clay. Montserrat is naked, pulling the raw material from the earth, covering her body with it and creating a vessel within the landscape, a hole in which she eventually lies, pressed against the earth. She is Black, and so the work inevitably bears all manner of meanings relating to race and place.

As is clear when you walk around Odundo’s Fitzwilliam show—whether the object is a pot made by Ko-Kipkimoi in Kenya or Ralph Simpson’s 17th-century charger featuring a pious pelican—or Ai’s collection of Chinese pots, some fake, bought at auction last year, shown with his own politically themed takes on blue-and-white porcelain at Kettle’s Yard, that connection between material, culture and identity is innate in the material and its various disciplines. The idea that an artform so central to humanity should be regarded as “applied” or “decorative”—or indeed that it can have moments in the spotlight before again fading away—is absurd.