Hollis Sigler

Until 19 March, Andrew Kreps Gallery, 22 Cortlandt Alley, Manhattan

In paintings and pastels on view here that span 1981 to 2000, the year before her death from breast cancer at age 53, Hollis Sigler is publicly grappling with disease and her own mortality, although you might not realise it at first. The compositions feature theatrical, fairy-tale imagery (ghostly dresses floating in eerily empty suburban settings, domestic scenes with classical statues looming portentously) that seems miles removed from the photorealistic paintings Sigler made in previous decades. But there is an exacting, diaristic realism lurking in the details that makes this exhibition, the first solo show of Sigler’s work in New York since the 1980s (organised with Baltimore’s Steven Scott Gallery), devastating. It is effectively an allegorical timeline of her battle with cancer, from her initial diagnosis and apparently successful treatment to its ultimately fatal recurrence. Some works are painfully intimate, with Sigler seemingly visualising her disappearance from her own life, while others amplify her internal struggle into stormy, scorched cityscapes. In text painted onto her frames she often alternates between quoting contemporaneous articles about cancer research and her own poetic reflections on her situation. Along the edges of one of the exhibition’s most dramatic paintings, I’m Holding Out For Victory, Winning Is My Greatest Desire (1998), in which an apocalyptic landscape in the foreground splits apart to frame a skyline ringed in celebratory fireworks, Sigler writes with willful, heartbreaking optimism: “Every good news story about this disease lifts my heart with hope… health is love is power.”

Tomás Saraceno, Free the Air: How to hear the universe in a spider/web,

(2022). Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles; Neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Andersen’s, Copenhagen; Ruth Benzacar, Buenos Aires; and Pinksummer Contemporary Art, Genoa. Photo courtesy The Shed

Tomás Saraceno: Particular Matter(s)

Until 17 April at The Shed, 545 West 30th Street

Arachnophobes, it’s time to face your fears and experience a spider’s world from their point of view. Tomas Saraceno’s monumental installation, Free the Air: How to hear the universe in a spider/web, part of a survey exhibition of the artist and climate activist’s work, asks visitors to enter a massive white sphere, across which two steel-wire nets have been suspended, then lie back and feel the vibrations of the soundtrack—a recording of spiders building their webs—skitter across the surface, as well as the movements of your fellow exhibition-goers. Being physically connected to every other person in the room, their every shift in posture communicating its way to your toes, is a feat few artists can achieve. But Saraceno does it subtly and effectively in the work. The rest of the show draws similar connections between individuals and the wider world, including the artist’s community-based Aerocene project, which seeks ways to take flight without fossil fuels. Visitors are required to book a time slot and sign a waiver to view the work.

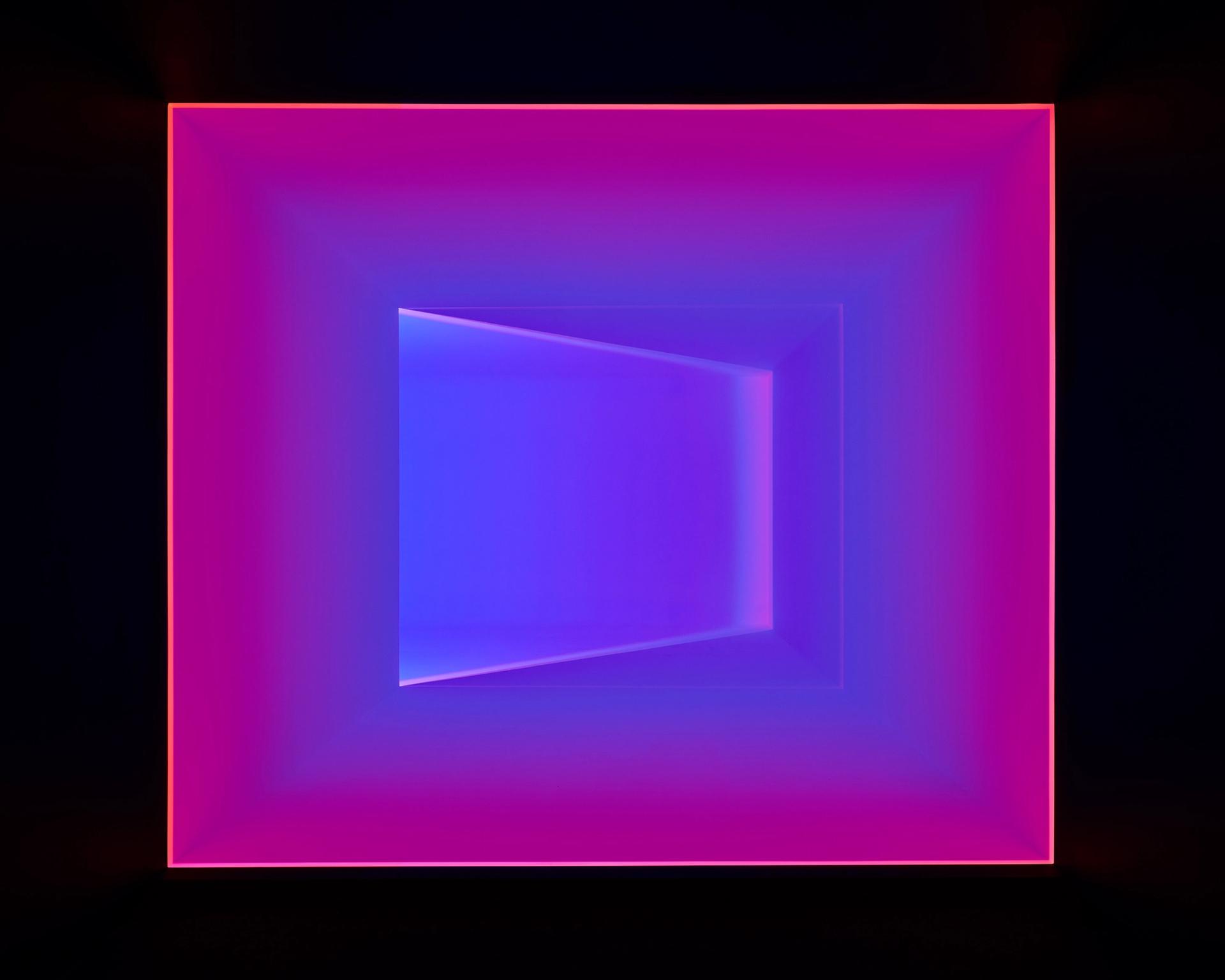

James Turrell: After Effect (2021). Courtesy Pace Gallery.

Ad Reinhardt: Colour Out of Darkness, curated by James Turrell

Until 19 March at Pace, 540 West 25th Street

It’s the last week to see James Turrell’s rapturous ode to the monochromatic colour studies of the painter Ad Reinhardt. The exhibition begins with the new installation After Effect (2021) by Turrell, an iridescent light sculpture made up of luminous rectangular planes, appearing three-dimensional, and leads to a presentation of seven red, black and blue paintings by Reinhardt from the 1950s and 1960s. Turrell designed the lighting and display of the exhibition, which gives each painting its own designated viewing space and aims to maximise the perceptual subtleties in Reinhardt’s work, which at first appear starkly minimal but contain a profusion of colour and depth. The show aims to draw connections between the artists’ seemingly antithetical practices. Turrell cites Reinhardt’s approach to colour as a lifelong influence, having first encountered the artist’s work while a student in the 1960s, when he attended a lecture by the artist at the Pasadena Museum.