Mont-Saint-Michel in Normandy, a unique rock crowned with a spectacular medieval abbey, consists of leucogranite, which is the reason why this steep tidal island was never washed away by the sea. But, as with England on the northern side of the Channel, the French mainland has long been at the mercy of coastal erosion and is losing land steadily.

In recent months, the France 2 television channel has repeatedly highlighted the plight of the cliffs of Normandy. Special attention has been given to Varengeville-sur-Mer in the Seine-Maritime department, where the church, which stands high on a cliff, faces the threat of soon disappearing into the sea. Varengeville was once the haunt of the protagonists of Impressionism, some of whom immortalised the church in their paintings, bathing its setting in soft colours and light. Small wonder, then, that the village and its Saint-Valery church are these days annually visited by tens of thousands of tourists.

Braque’s final resting place

However, the cliffs at Varengeville-sur-Mer and nearby places like Dieppe are powerless against the onslaught of the sea; they lack the durability of Mont-Saint-Michel.

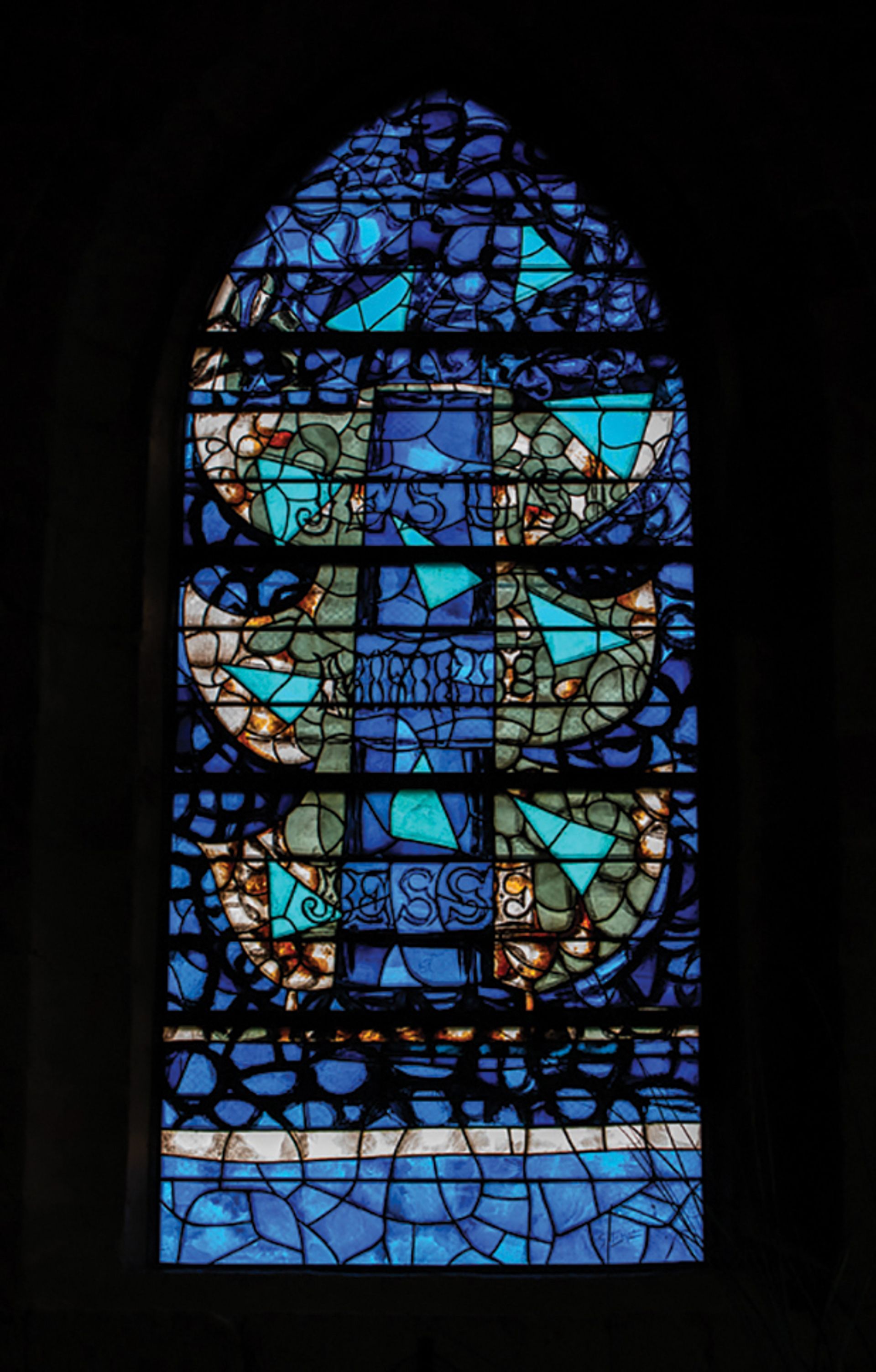

Georges Braque’s 1961 stained-glass window in the church

Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and Corot were drawn to Varengeville—and eventually the Cubist artist Georges Braque, who became a resident in the village and since 1963 lies buried in the cemetery adjacent to the church. It was Braque who, at the suggestion of the then French minister of culture André Malraux, designed the wonderful stained-glass window depicting the Tree of Jesse in the choir of Saint-Valery.

The church, whose present building dates back to the 11th century, combines Romanesque with later architectural elements. In its place once stood the sanctuary of the monk Valery, who had come from Auvergne and whose mission earned him the name “Apostle of the Coastal Cliffs”. However, according to records, the cliffs had at the time been half a mile inland, whereas today the water laps them. As Arnaud Gruet, a local councillor, points out, the church is only 10m away from a piece of land that is rapidly sliding towards the nearby vertical cliff. This cliff is said to recede by an average of 40m—here and there by up to a metre a year—from the untameable sea.

Consisting mostly of chalk, mixed in the upper parts with sand and clay, the cliffs of the Seine-Maritime department—which are up to 100m high—are easy prey to coastal erosion. This process is caused by storms, wind, strong wave action and rising sea levels due to global warming. At Dieppe, for example, a total of 20,000 cubic metres of cliff disappeared in a collapse in 2012.

Saint-Valery church has, since the turn of the millennium, received repairs to some walls and the foundations, as well as the roof and beams Photo: © Philippe Picherit

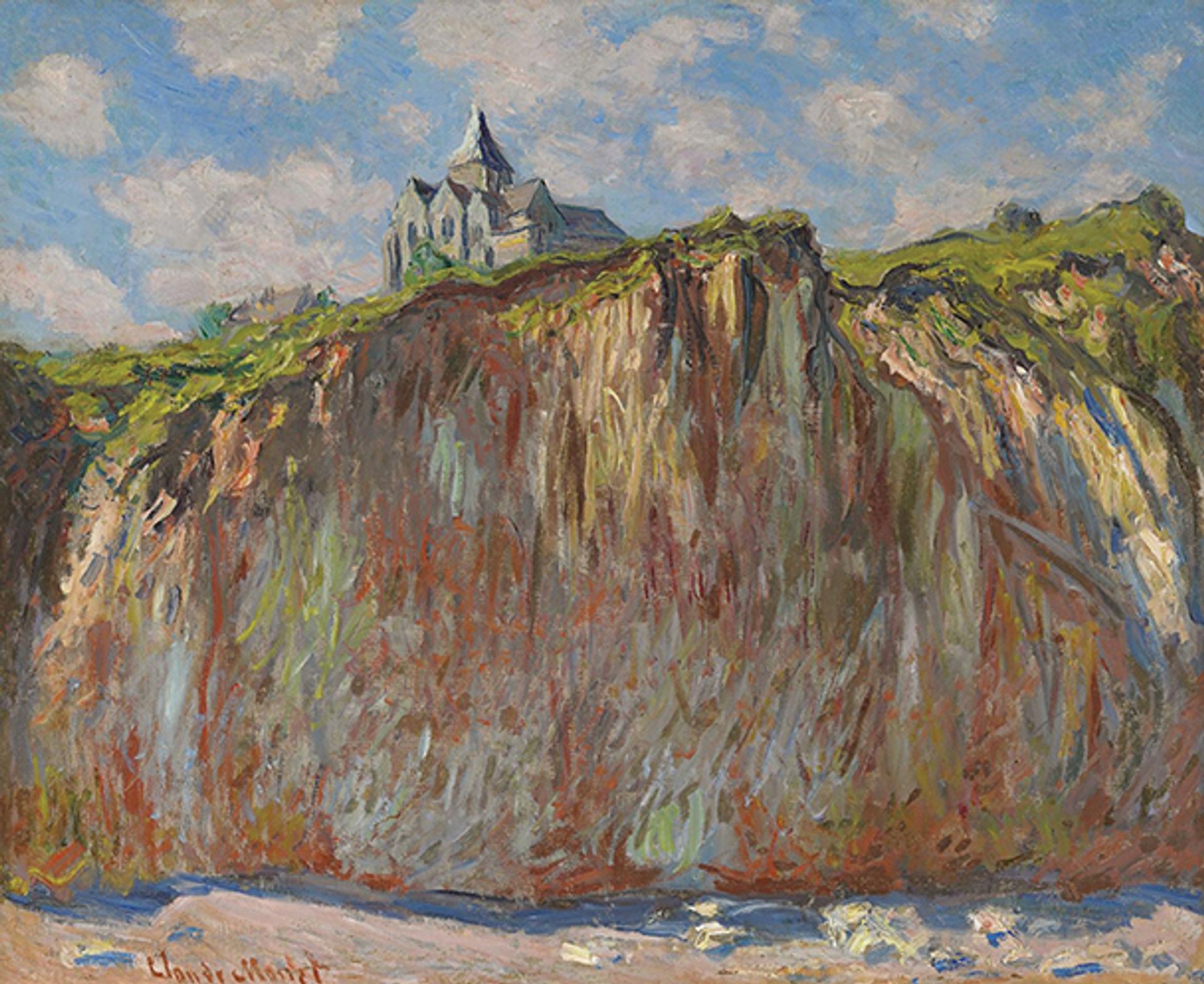

There is no doubt that a bleak future hangs over the entire coast of the department—in other words, 46 municipalities with 300,000 inhabitants. Geologists estimate that the Seine-Maritime department will lose 230ha of coastal land within 20 years. If a gap opens somewhere, the water eats its way inexorably into the land behind. But how aware was Claude Monet of such dangers? In his 1882 painting, L’Eglise de Varengeville, effet matinale, the church stands on a defiant coastal rock—albeit not far from the abyss.

Saving Saint-Valery

Diverse methods to combat coastal erosion have long been tried in France. But, just as in the west, where the Atlantic ravages Europe’s highest dunes, there is little hope for the cliffs of the Seine-Maritime department. And here, Varengeville-sur-Mer clearly takes centre stage. The customs cottage, like Saint-Valery church repeatedly painted by Monet, has already disappeared. This was built during the Napoleonic blockade of Europe, and Monet obtained the keys for use as a resident. It, too, stood on unstable ground.

At least the structure of Saint-Valery has, since the turn of the millennium, received repairs to some walls and the foundations, as well as the roof and beams. “Just imagine,” Gruet says: “Before, you could even see inside the church through the crack in one of the side walls.” For these improvements, which cost €1.5m, 46% of the money came from the state and 25% from the Seine-Maritime department. The question as to the role of public subsidies is, in Gruet’s words, not easy to answer: “The question is an almost philosophical one, since Saint-Valery church is on the one hand a place of worship, on the other—being classified as a historical monument since 1924—part of the national cultural heritage.” Whatever the case, according to Gruet, the church, which is constantly changing in level due to moisture in the ground, has, since the works, been held together artificially. “It will eventually slide into the abyss, even collapse piece by piece and fall into the sea,” he says.

To avert the inevitable disaster, an expensive intervention is needed; and following a public appeal five years ago, the community of Varengeville has been receiving donations. But how exactly can Saint-Valery be saved? One solution would be to disassemble the church into individual parts and reconstruct it somewhere inland. The other, radical option has expensive US precedents: the church would be moved entirely onto rails or dollies and transported to a new location. But would the already endangered ground beneath the church and cemetery be able to bear the weight of the machinery required? The feasibility study alone, which would also have to include the new location, would cost €400,000 to €600,000—a small part of the many millions required for such a venture, as Mayor Patrick Boulier points out.

Claude Monet’s L’Église de Varengeville, effet matinal (1882) Private collection

Monet’s enduring legacy

If Saint-Valery church falls victim to coastal erosion, Varengeville cemetery will also disappear into the sea—and, with it, the grave of Georges Braque, his wife and their servant. François Mitterrand came here several times during his tenure as France’s president; villagers recall that he would sit down on the wooden bench behind the church and abandon himself to the panorama and his thoughts.

Boulier consoles himself with the fact that if a disaster cannot be averted, Varengeville will at least retain this panorama—and the art world will still have the Impressionists’ paintings. A particularly fine view by Monet, L’Eglise de Varengeville; soleil couchant (1882), sold at Christie’s in London in 2014 for £5.68m. Allegedly, the artist’s first encounter with the church was accidental; he chanced on it in the course of a walk along the coast. He was to paint four versions of the same picture.