The recognition of the rights of rivers, by granting them legal personhood and appointing custodians to speak for them before courts and tribunals, is a phenomenon that is carrying the Biennale of Sydney into new terrain.

José Roca, the Colombian artistic director, even invited selected rivers to become “participants” in the Biennale, which opened on 12 March and continues until 13 June, along with 59 artists from 33 countries. “The rivers will be represented by ancestral custodians or contemporary custodians that will speak on their behalf,” Roca says.

One such river is Ecuador’s Vilcabamba, which successfully sued local authorities over its polluted state. “If rivers can have a legal voice, why wouldn’t they have a voice that can engage in a conversation with other participants in the Biennale?” Roca asks. “That is the basis for us inviting those rivers as participants. You can speak for a thing, but it would be better if that thing spoke for itself.

We have had to imagine ways in which bodies of water can speakJose Roca, artistic director

“We have had to imagine ways in which bodies of water can speak. The way we found was the most effective is custodians from the given river, say the Yarra or the Martuwarra/Fitzroy or the Barka [in Australia] or the Atrato in Colombia, talk to the camera in different forms of vernacular poetry—spoken word, sung, or verse or rap. And they tell stories about the river as if it was the river speaking.”

Installations on display at the Cutaway at Barangaroo as part of the 2022 Sydney Biennale. Courtesy of Sydney Biennale and Document Photography

The 1,500km Magdalena River, Colombia’s biggest and most important waterway, has a large presence in the Biennale. The Magdalena has no legal personhood, but it does have artists fighting for it. One of them is Los Angeles-based Carolina Caycedo, whose parents are from Colombia.

The Magdalena is “still mighty”, Caycedo tells The Art Newspaper. But it suffers from issues including deforestation, erosion, pollution and recent damming. Plans for another 15 dams “lurk like monsters” over the country’s ecology, Caycedo says.

Caycedo moved to the small Colombian town of La Jagua in 2014, where she lived beside the Magdalena for six months and ran workshops for local residents involved in grassroots protests against the El Quimbo dam, which was under construction at that time. “We facilitated workshops around contemporary dance, performance, theatre of the oppressed and puppetry to help them navigate the moment of resistance and struggle,” she says.

Water mark

One of Caycedo’s works in the Biennale is a mural titled Yuma, or The Land of Friends, in which the course of the Magdalena is depicted in overlapping satellite imagery. “You can see the devastation along the river, how they have taken sand and land and material from different parts of the riverside to build a dam,” Caycedo says.

Also visible are the so-called “man camps” for infrastructure workers, which are associated with prostitution, drugs and alcoholism. This has resulted in the birth of “children of the dam”, whose fathers are unknown to them.

Caycedo says Yuma is a damning critique of satellite imagery as a Western method of depicting a landscape, because the human suffering caused by ecological devastation is left out.

“I believe cultural institutions, museums and biennials are places to debate pressing issues in our society,” Caycedo says. “Artists have been complicit also in the processes of colonisation and of displacement, and now it’s important to subvert these canons through the same practice.”

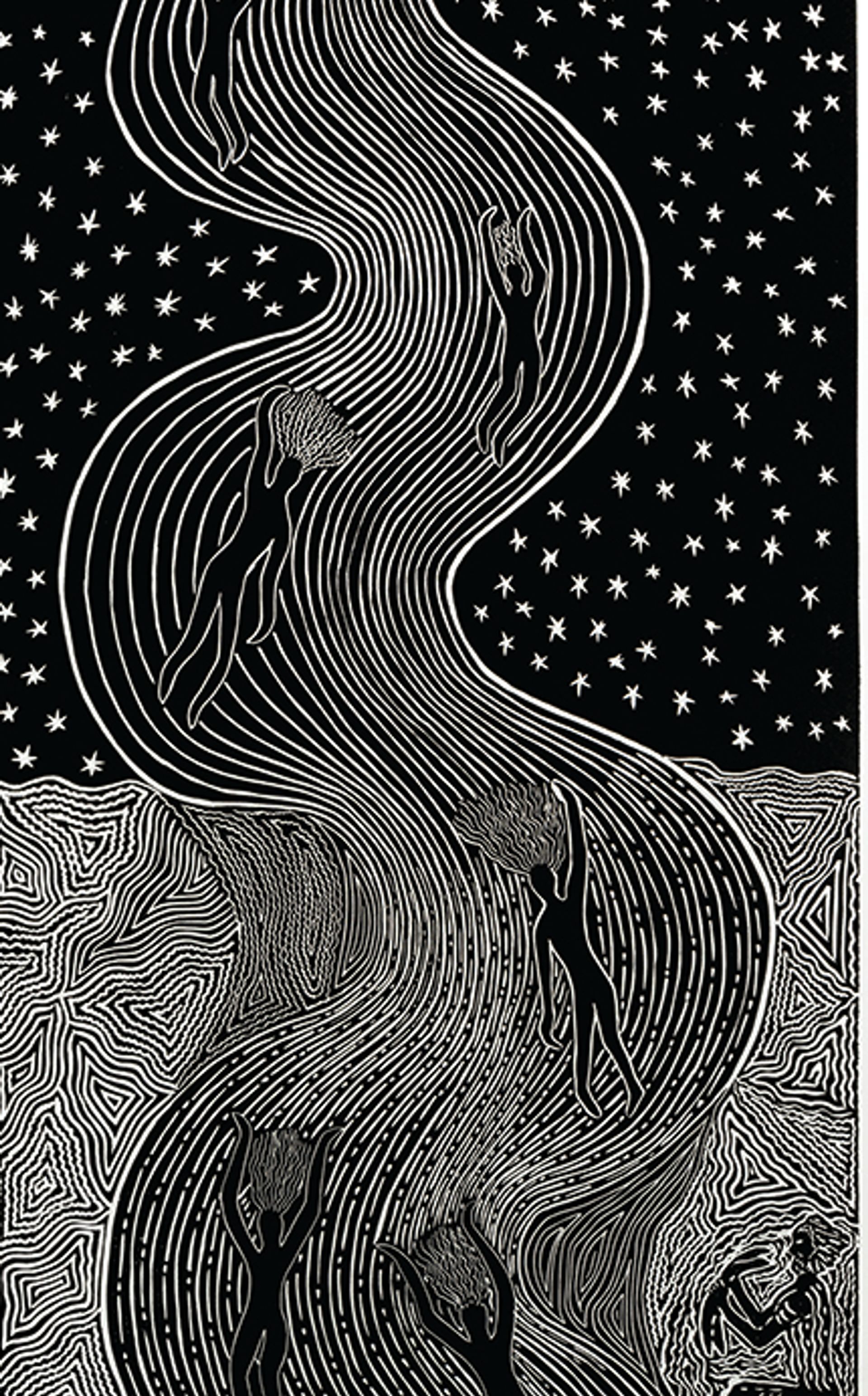

Badger Bates's Witu witulinja: Seven Sisters (2017). Courtesy the artist. Photograph: Alex Rosenblum. © Badger Bates.

Many First Nations artists are exhibiting at the Biennale, including Badger Bates, a Barkandji elder who grew up along the banks of Australia’s Barka/Darling River. Bates shows the linocuts in which he has preserved stories handed down from his grandmother, Granny Moysey.

Sheroanawë Hakihiiwë, an Indigenous Yanomami artist from the Venezuelan Amazon, shows his botanical drawings on paper made from local fibres. His drawings include iconography from Yanomami culture and its application in basketry and body painting.

• Biennale of Sydney: Rīvus, various venues across Sydney, 12 March-13 June

• For more on the Sydney Biennale listen to The Week in Art podcast this Friday where we speak to the artistic director José Roca and Alessandro Pelizzon, an academic and one of the founding members of the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature and of the Australian Earth Laws Alliance