The Centre Pompidou’s function has always been multidisciplinary. Some of its most memorable moments have occurred when it brings its many sections together—not just the most celebrated part, the Musée National d’Art Moderne, but the founding industrial design centre, the Centre de Creation Industrielle (CCI), now absorbed into the museum, and Ircam, the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique, which remains a discrete element within the complex.

The series of events Mutations/Creations, begun in 2017, is in this tradition, focusing on the interaction of digital technology with creative activity, fusing art and science across a range of exhibitions and events integrating the centre’s different departments. The fifth iteration is, in many ways, a definitive Centre Pompidou show: Réseaux-Mondes, or Worlds of Networks, featuring 60 artists, designers and architects, looks at the proliferation of networks both technologically and socially. Of course, the internet and its deepening complexities dominate the show.

“It’s completely an exhibition in the spirit of the Centre Pompidou,” says Marie-Ange Brayer, the co-curator of the exhibition with Olivier Zeitoun. She describes Worlds of Networks as “more than just a multidisciplinary exhibition”—it connects art, design, architecture and film, but Ircam’s involvement, in particular, means that the exhibition is a “connection between artistic practices and scientific research, to really build the bridge between both”.

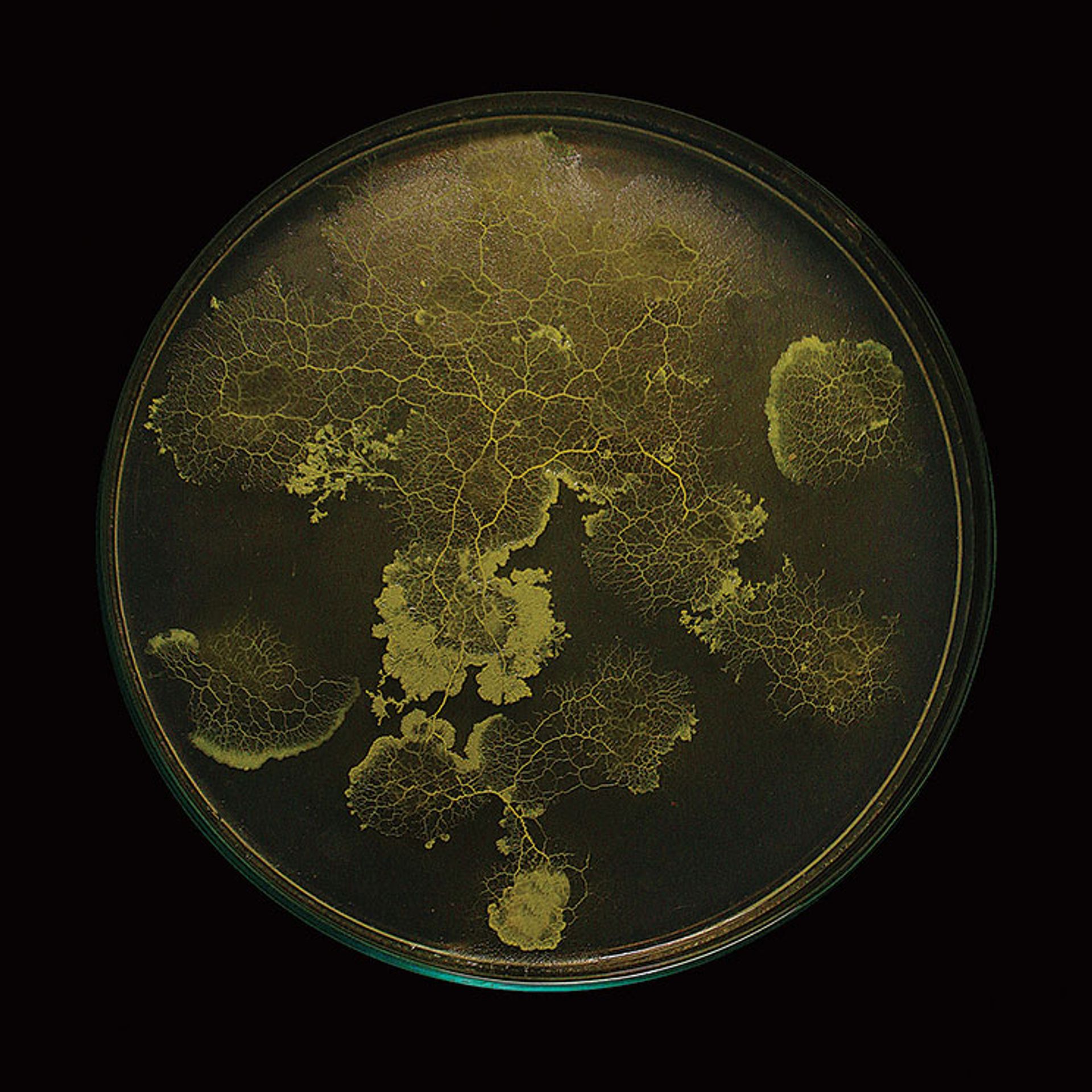

EcoLogicStudio’s GAN-Physarum project (2021) placed a living organism (mould) on a city map to show parallels between organic and urban growth Photo: courtesy of Hassan Khan; © Rc16, Urban Morphogenesis Lab, BPro UD, The Bartlett UCL

It is also an event in which the CCI part of the Pompidou comes to the fore. As a forebear to Worlds of Networks, Brayer cites Les Immatériaux, the 1985 CCI-led show, curated by the Post-Modern philosopher Jean-François Lyotard. The artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, Hans Ulrich Obrist, once told The Art Newspaper that the exhibition had “proved a huge influence on my generation of artists… It really anticipated our digital age; it looked at what it meant to move from material objects… to immaterial information technologies.”

Brayer says that she and Zeitoun are “like the kids” of Lyotard and “are trying to work in the same manner… to create a dialogue between artistic practices, scientific approaches, philosophical issues”. Zeitoun adds: “There’s an experimental dimension in this kind of platform. And that’s the way also we bring together different types of materials: prototypes, artworks like sculpture, installation, and even, in Worlds of Networks, investigational works.”

The show goes back as far as the 18th century and Diderot and d’Alembert’s encyclopaedia, where systems of knowledge were conceptualised not as a tree but as a network for the first time. “It’s important for us to show all these different layers of understanding, connecting the organic and cognitive dimension of the network,” Brayer says. The show explores how ideas have shifted as technology and society have developed. One section focuses on cybernetics in the post-war period—“where the first idea of a global village appears”, Brayer says—and “the influence of theories of information in architecture”, such as the French-Hungarian architect Yona Friedman’s megastructures, or New Babylon, the utopian city imagined by Constant Nieuwenhuys, the artist and Situationist. Spatiovore (1959) one of Nieuwenhuys’s models for New Babylon, is among the exhibits.

What is the shaman, the oracle in the AI machine, which becomes a new type of tool to connect humans and non-humans?Olivier Zeitoun, curator

But as Zeitoun says, the show progresses from post-war utopian projects to analysing how, in the era of the internet, “the network has become a synonym of invisibility, ubiquity, sometimes exclusion and most often the mercantile necessities of capitalism”. Works by Neïl Beloufa, Simon Denny and Mika Tajima “present themselves as a sort of social satire of what’s happening today”, he says. “There’s this very interesting tension between a critique of networks that will focus on this absurdity of the online experience and, at the same time, it gives poetic visions of this experience as a multitude, what it allows in terms of collective thoughts and feelings.” Tajima’s ongoing Human Synth project, for instance, uses live Twitter data to produce various artistic forms, in the current show a screen-based work with endlessly morphing coloured smoke. “There’s this collaboration between the artist, the developer [and] the scientist to work with these technologies that are the invisible infrastructures of this experience.”

Ghost in the machine

A core element of the exhibition is the interface between humans and non-human entities (a cornerstone of Bruno Latour’s 1980s theories of the “actor-network”). Among the most interesting examples is the use of the unicellular slime mould physarum polycephalum in experiments by the architectural practice ecoLogicStudio and in works by Jenna Sutela, the Finnish artist. EcoLogicStudio are creating “an osmosis” between artificial intelligence (AI) and biology, Brayer says, by creating a new simulation programme based on the slime mould’s movement and then using AI “to develop a new protocol of urbanism”. And Zeitoun says that Sutela—whose interest in interspecies communication has also led to a work combining neural networks and Martian languages channelled by a 19th-century medium—is using the same connection between the organic and the virtual to ask: “What is the shaman, the oracle in the AI machine, which becomes a new type of tool to connect humans and non-humans, a new type of tool to create a random language that would be beyond human perception?”

It takes us back, Zeitoun says, to “the ghost in the machine” explored in Les Immatériaux, that multimedia presentation that so inspired Parreno and other creative practitioners in the 1980s—a phenomenon “that artists are still interrogating in new ways today”.

• Worlds of Networks, Centre Pompidou, Paris, until 25 April. Connecting Worlds, the 2022 Vertigo Forum symposium, is at Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (Ircam), Paris, 9-11 March